Life Lines: Phenotypic plasticity and moments of surprise

By Elof Axel Carlson

In my youth I read Joyce Cary’s novel Herself Surprised and was moved by his opening chapter describing a woman, rather frumpy looking, hustling and puffing her way through a train station only to realize she was looking at a mirror image of herself. The book’s title and theme engaged my attention.

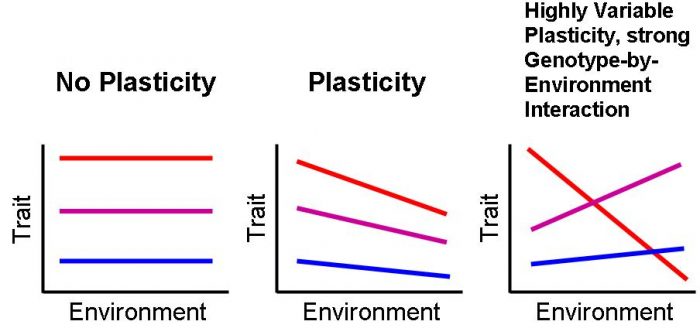

In my own life I have had a few “myself surprised” moments. One of them came as I read an article in American Scientist by evolutionist David Pfennig who works at the University of North Carolina. He discusses a concept called “phenotypic plasticity.” When Mendel worked out his laws of genetics he distinguished between the phenotype (appearance) and the genotype (genetic composition) of the pea plants he studied. A yellow pea could be heterozygous or homozygous and look the same. You had to do a genetic cross to determine the genotypes form the phenotypes of the traits you studied.

In Pfennig’s study, phenotypic plasticity is a surprise. An organism can have itself or its progeny change characteristics very rapidly in moments or days instead of mutational change which takes generations or millennia to distinguish new populations. Some species of birds or animals can change color seasonally. Some social insects like bees or wasps or ants can change body shape and function by feeding the developing embryos in the hives or by shifting a mode of reproduction from fertilization to cloning or parthenogenesis (virgin birth). They are adaptations to changes in seasons or changes of a sudden nature (like flooding or a drought). Unlike the survival of finches in the Galapagos islands that take decades or millennia to change through natural selection of mutations arising spontaneously, phenotypic plasticity enables some organisms to resist extinction by a rapid response.

I realized that my own body was subject to this phenotypic plasticity as I turned 85. I knew I was getting older physically as I began to grey and my skin wrinkled. I feel as if my mitochondria are being depleted and the energy requirements of my cells are no longer being met in all my tissues. I am the reverse of Oscar Wilde’s portrait of Dorian Gray.

I have accelerated the aging process in my advanced old age, a fate that will befall all who are lucky to live as long as I have. One of my undergraduate students at Stony Brook University did a project on aging in identical twins. He got photo albums of elderly identical twins and matched their appearance by scissoring copies of their photos and matching the left of one twin to the right of the other twin when they were separately photographed. It was surprising how much they fit, while nonidentical same sex twins did not do this and produced asymmetrical faces.

The surprise is how a body can use its genotype to maintain a sameness in the two twins who are identical at any age. We don’t select for each year’s features of our faces and bodies. Something else is going on that plays out in our lifestyle as we age. It makes sense that our environments can shape us through the careers we choose and opportunities that come our way. But the biological changes that take place are much more difficult to explain and show that much is to be learned about the “plasticity” in our lives and how it works at a scientific level.

Elof Axel Carlson is a distinguished teaching professor emeritus in the Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Stony Brook University.