Harvest Times: Small ways to make a big difference in helping wildlife

By John Turner

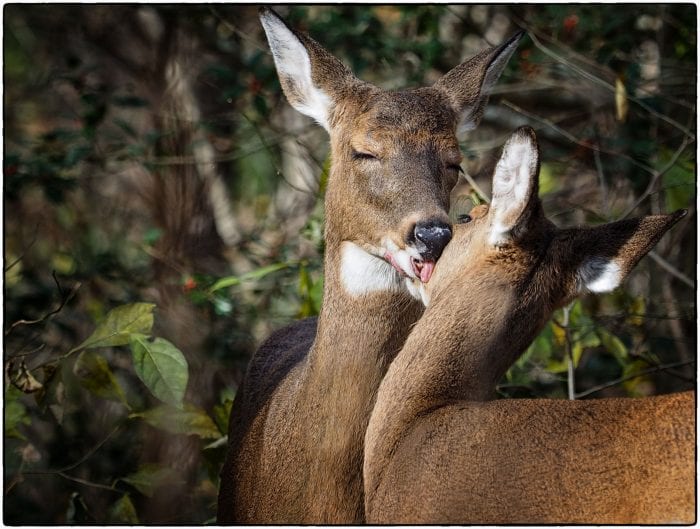

A White-tailed deer nibbling peacefully on lush green leaves along the roadside, its namesake tail twitching in the twilight of early evening. A screeching, Red-tailed hawk drawing circles around the sun, the bird of prey’s discordant call still being used today to emphasize the most dramatic moments in western movies. Its distant cousin, an Osprey, drops into a rapid stoop, hitting the water with knife-tip sharp talons flared like the legs of a claw lamp, a strategy to enhance capture of slippery fish.

The nightly summer show of incandescence put on by the otherworldly display of fireflies. The seasonal parade of Monarch butterflies feeding on seaside goldenrod at coastal beaches, filling up their migratory fuel tanks on their autumn journey to Mexico. A Grey squirrel sitting on a tree branch in a light rain, feeding on a walnut, adorned with a walnut-stained beard and moustache, its fluffy tail arched over its back and head serving as a most effective umbrella. The dancing flights of Ruby-throated hummingbirds nectaring in wildflower beds, their improbable tubular tongues gaining sustenance through the nectar the plants calculatingly provide.

If you’re like most residents who spends some time outdoors you’ve probably had one or more of the above experiences, or something similar, connecting you to the diversity of wild animals which grace Long Island’s parks, ponds and natural areas. Maybe these experiences have occurred through happenstance or due to your desire to seek them out. Either way, wild animals, what we call “wildlife,” fully living their independent, yet intertwined lives, enrich both ours and theirs and naturally leads to the question: what actions can I take to help wildlife?

Well, the short answer is there are dozens of direct and indirect things each of us can do to protect wildlife both here and further afield. A direct action? Making sure you recycle broken fishing line and not leaving it in or along the edge of a pond where aquatic wildlife, like ducks and swans, and geese, can get entangled and die.

Driving more slowly and looking for box turtles and other animals that might be in harm’s way on the road way. Minimizing bright outdoor lighting which adversely affects nocturnal animals (motion detecting lights are a good compromise between security and the needs of wildlife for darkness).

Indirect actions? Reducing energy and water use, composting the compostable portion of your garbage, recycling the recyclable part, and most importantly, generating less garbage to begin with.

Following are but a few actions for you to consider and there are many, many more, limited only by your imagination. These measures can be placed in two basic categories: things you should do and thing you shouldn’t.

Taking first those activities that you shouldn’t — paramount among them is to avoid the use of pesticides. Despite greenwashing by the chemical industry, it’s important to remember that pesticides are chemical poisons intentionally designed to kill things and they often kill many other insects and other animals besides the ones they’re designed to.

Rampant pesticide use (we use about one billion pounds of insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides annually; yes, billion, that’s not a typo) is the leading cause for the decline of scores of important pollinating insects including native bees, flies, butterflies, moths, beetles, and the European honey bee.

Many non-target mammals, birds, fish, and numerous reptiles and amphibians are harmed or killed by pesticide use too (many box turtles exposed to pesticides appear to develop painful abscesses in their middle ear cavity which can be life threatening). There is much on-line information about less destructive ways to control undesirable insects, weeds, etc., than through using poisons.

Another “don’t” action involves your cat. Cats, both feral and free roaming pets, are the leading cause for small mammals and bird deaths and their decline. Billions of mice, voles, and hundreds of millions of songbirds, involving dozen of species, are killed by cats annually in the United States. And collar bells on cats make no difference as birds don’t associate bells with danger.

Most people don’t open the front door to let their dog out, freeing it to roam the neighborhood, but don’t think twice about letting the cat out where it can and does wreak ecological havoc. While it is difficult to make a pet cat used to going outside exclusively into an indoor cat, there are transitioning strategies you can employ available on-line for review. And make your next pet cat an indoor one!!

Now for the do’s — do make your yard friendly for wildlife! Make it a cafeteria and shelter! This effort should start by planting or expanding the use of native plant species which are life sustaining for hundreds of insects which form the base of local food chains.

Doug Tallamy, in his wonderful new book ,“Nature’s Best Hope,” states that a White oak tree can sustain several hundred different species of insects — insects, both in adult and larval forms (caterpillars) that birds like Black-capped chickadees and Downy woodpeckers need to survive.

Another great native plant — a shrub — is Common elderberry (yes, THAT plant whose berries are made into wine). The small white flowers provide nectar to a variety of small pollinating insects and the red-purple berries, often produced in copious amounts, are eaten by a number of songbirds. Compare these species to non-native exotic plants, say a Winged Euonymus or Arborvitae, typically planted by homeowners and landscapers. These plants are ecological deserts never becoming part of the local food chain since no or few insects feed upon, insects which sustain so many other living things.

Add sterile lawns and we’ve created landscapes around our home that provides little in the way that wildlife needs. In contrast, planting native wildflowers, shrubs, and trees is a highly effective strategy for hosts of animals that feed on the bounty that native plants provide in the form of nectar, seeds, fruits, and nuts.

And leaving leaf cover in your flower beds and other out of the way places during the autumn cleanup provides shelter from the winter’s cold for a variety of overwintering caterpillars and other insects.

Placing decals on your home’s windows is another measure you can take around your house to meaningfully help birds. Nearly a billion birds in North America are estimated to die annually from flying into building windows they don’t see, due to either of the two deadly characteristics windows possess — transparency and reflectivity. Hummingbirds are especially common collision victims. There are several type of attractive decal products available for purchase on-line which, when installed, help enable birds to see windows for what they are.

By now you may have had the thought — John, you’ve discussed these other ways to help wildlife but what about perhaps the most obvious way: by feeding birds. In truth, that’s a common and pervasive misperception as feeding birds does nothing to help them survive since no wild bird species depends upon backyard bird feeding stations to continue to exist.

Wild birds are quite adept at finding enough wild food for themselves even during the winter and for their young during the breeding season to survive. They don’t need or depend on the seed, suet, sugar water, jelly, and oranges many homeowners put out to entice them. And the species that frequent backyard feeders — Black-capped chickadees, Tufted titmice, Common grackles, Carolina wrens, and a variety of woodpeckers — are common suburban birds whose populations are doing well. The species whose populations are declining and are in trouble — many migratory warblers, vireos, swallows, swifts, nighthawks, thrushes, and flycatchers — rarely, if ever, frequent feeders.

So, if you’re feeding birds because you enjoy watching them up close that makes sense (a point hard to argue given their beauty and fascinating behaviors!), but if you’re feeding them because you think individual birds and species of birds need your help, it would be better to spend the bird feed money by writing a check to a bird conservation advocacy organization like the National Audubon Society (the local chapter is the Four Harbors Audubon Society) or the American Bird Conservancy.

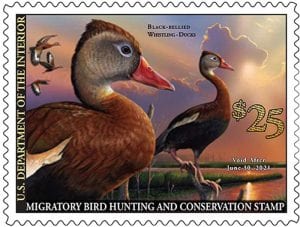

Even better, you should take some of the money you’ve saved and buy a federal Duck Stamp, one of the best kept secrets in conservation. More than five million acres of wildlife habitat have been permanently protected, purchased through the use of Duck Stamp funds, including much of the National Wildlife Refuge system (we have some wonderful refuges on Long Island you can explore like Wertheim and Elizabeth Morton).

Simply stated, animals need habitat to survive. Like us, they need water, food and shelter and the Duck Stamp program has provided a way to protect huge expanses of habitat. Buying land that contains valuable wildlife habitat can help bird species survive. Duck stamps are available for purchase at a place which has been much in the news lately: your local Post Office.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

*This article first appeared in Harvest Times 2020, a supplement of TBR News Media