Coronavirus has Outsized Impact on Communities of Color in Suffolk

Black and Latino communities have been disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, and on Long Island where communities are as segregated as they are, much of it comes down to geography.

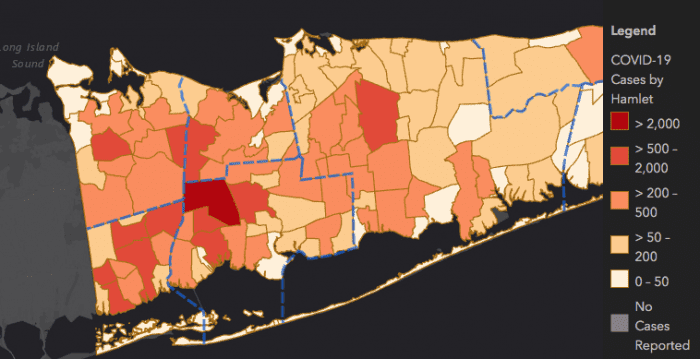

COVID-19 cases in Suffolk County have an identifiable curve. Data on maps provided by Suffolk County show a darkening red on a path rolling from the eastern end of the Island toward the west, homing in on the western center of the Island — Wyandanch, Brentwood and Huntington Station. In such areas, data also shows, is also where many minority communities live.

Data from New York State’s Department of Health maps shows the coronavirus has disproportionately harmed black and Latino communities. Brentwood in particular has shown 3,473 cases, or nearly 55 per 1,000 persons. New York State Education Department data shows the Brentwood school district, as just an example, is nearly 85 percent Latino and almost 10 percent black. Huntington Station, another example of a location with large black and Latino populations, has just over 1,000 cases, or 33 persons per 1,00 have the virus. As testing continues, those numbers continue to grow.

Though data showing the numbers of COVID-19 deaths is out of date, numbers from New York’s Covid tracker website show the percent of black residents who died from the virus was 12 percent, higher than the 8 percent share of the overall Suffolk population. For Latino residents, the fatality percent was 14 percent, lower than their population of 19 percent.

While whites make up 81 percent of the population, their proportion of residents confirmed with the virus is only 64 percent. If the white population were suffering the same proportionate death ratio higher than their overall population, then dozens more white people would have already perished from COVID-19.

“I’m not surprised by the information given,” said Brookhaven town Councilwoman Valerie Cartright (D-Port Jefferson Station). “We need to be testing as much as possible, we need to be tracing, we need to make sure once we get that under control, we need to make sure people get treated.”

The COVID Hot Zones

Toward the beginning of April, Suffolk County established three “hot spot” testing centers in Wyandanch, Brentwood and Huntington. Those sites quickly established a higher rate of positive cases compared to the county’s other sites, especially the testing center at Stony Brook University. A little more than a week ago, such hot spot sites were showing 53 percent of those tested were positive. On Tuesday, April 29, that number dropped slightly to 48 percent hot spot positive tests compared to 38 percent for the rest of the county.

Though such testing centers didn’t arrive until more than a month into the crisis, county leadership said plans for such sites developed as data slowly showed where peak cases were.

“When we started working with the IT department to find the addresses where these cases were, Southold was leading,” said Dr. Gregson Pigott, the Suffolk Department of Health Services commissioner. “Then Huntington Station became the hot spot. Then Brentwood became the leader in cases, and to this day Brentwood has the most cases.”

Suffolk County has also started plans for recovery after things finally start to open up. The Recovery Task Force is being headed by multiple partners, including Vanessa Baird Streeter, an assistant deputy county executive.

The task force will need to provide aid, but Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone (D) said there needs to be emphasis on addressing the glaring inequities, and put an emphasis on “coming back stronger.”

“There’s no question the issue is we know there have been disparities,” he said. “The crisis like this is only going to exacerbate those issues and have those disparities grow.”

But as it became clear to officials the virus was greatly impacting the majority of minority communities harder than others, said communities were watching day by day how the virus was upending lives, infecting whole households and leaving many without any chance of providing for their families.

Latino Community During Coronavirus

Martha Maffei, the executive director for Latino and immigrant advocacy group SEPA Mujer, said Latino communities are hit so hard especially because of many people’s employment. Either they were effectively let go, or they are working in jobs that if they tried to take time off, they would be out of a job. Instead, such workers, even in what has already been deemed “nonessential business,” are still going to work even in places where workers have already gotten sick.

“We were receiving calls of jobs they know the workplace has been infected, they continue to ask employees to come to work,” she said. “They don’t have the option to say no, because they’re basically forcing them and they don’t want to lose their jobs.”

A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in early April found approximately 41 percent of Latinos have lost their jobs since the start of the pandemic, compared to just 24 percent white and 32 blacks being laid off or furloughed. This jives with research showing about 50 percent of people on the lower income scale have either lost their job or had to take a pay cut.

Many who relied on their jobs to support their families have now lost them completely, and since many are undocumented, they have no access to any kind of federal assistance. In homes that are often multigenerational and cramped, workers out on the front lines come home and have very little means of sequestering themselves.

SEPA Mujer also advocates for women in violent domestic situations, and Maffei said its crisis hotline phone has been ringing daily. Bellone has told reporters the incidents of domestic violence are up 3.5 percent from early to mid April.

At issue is the immigrant community’s trust in local government and law enforcement, and that same government’s ability to get the life-saving and virus-mitigating information to them.

The hot spot testing centers now include Spanish-speaking translators, at least one per each, according to Pigott. Bellone also announced, working with nonprofits Island Harvest and Long Island Cares, they are providing food assistance to visitors at the testing sites. Brentwood is already seeing those activities, and Wyandanch will also start providing food April 30.

When the first hot spot site opened in Huntington Station, Maffei said she had clients who were struggling to schedule an appointment. Though she suspects it has gotten better with more sites opening up in western Suffolk, true help to the community should come in the form of facilitating access to information.

“We’re trying to do the best we can, but a lot of people don’t have access to the internet, don’t have Facebook,” Maffei said.

Pigott related the county is providing multi-language information via their website and brochures at the testing sites, but community advocates argue there is a demand for such details of where people can get tested and how they can prevent infection, straight into the hands of people, possibly through mailings or other mass outreach.

Why Minority Communities are Vulnerable

Medical and social scientists, in asking the first and likely most important question, “why?” said the historic inequities in majority minority populations are only exacerbated by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Dr. Johanna Martinez, a physician with Northwell, is in the midst of helping conduct a research project to work out the variables that are leading to how the pandemic has deepened and exacerbated existing inequities.

“It’s not something biological that is different between black and Latino people. It really is the historical inequities, like racism, that has led to the patients being marginalized,” Martinez said. “It is most closely linked to social determinants.”

The links are plain, she said, in socioeconomic status, and perhaps most importantly, one’s access to health care. Immigrant communities are especially likely to lack insurance and easy communication with doctors. It’s hard for one to know if one’s symptoms should necessitate a hospital visit if one also doesn’t have a doctor within phone’s reach. It also means an increased spread of the virus and a potential increased load on hospitals.

“If you’re uninsured, the place where you’re going to get health care from is the emergency room,” the Northwell doctor said. “Right now, we’re trying to use telemedicine, but if you don’t have an established primary care doctor, you don’t have the ability to speak to the doctor of the symptoms you’re having and if this is something you can stay home for or go to the hospital.”

Current data released by New York State has mostly been determining age, as its well-known vulnerable people include the elderly, but Martinez’ data is adjusting for other things like comorbidities. Data shows that diabetes, hypertension and obesity put one at a higher risk for COVID-19-related death, and studies have shown poorer or communities of people of color are at higher risk for such diseases.

“It’s almost like a double whammy,” she said. “It’s something that makes them even more vulnerable to a very serious disease.”

“It’s not something biological that is different between black and Latino people. It really is the historical inequities, like racism, that has led to the patients being marginalized.”

— Dr. Johanna Martinez

Housing is also a factor. Once one leaves the hospital, or on recommendation from a doctor, it’s easy to tell people who are showing symptoms to isolate a certain part of the house, but for a large family living in a relatively small space, that might just be impossible.

Whether Suffolk’s numbers detailing the number of confirmed COVID patients is accurate, Martinez said she doubts it, especially looking at nationally. Newsday recently reported, upon looking at towns’ death certificates compared to New York’s details on fatalities, there could be many more COVID deaths than currently thought.

“We need more testing to see the prevalence in certain communities,” she said.

Cartright, who works as a civil rights attorney, said these factors are what the government should be looking at as the initial wave of COVID-19 patients overall declines.

“We know black people are dying at a disproportionate rate,” she said. “We need to look at how many people are living in the same household, how many people actually have health care, how many are undocumented who were scared of going to the emergency room. There are so many factors we need to be able to take a look at.”