Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory set to begin restoration of 1850 seawall

Over a decade before the Civil War, brothers John, Walter and Townsend Jones recognized that they needed to protect the land at Cold Spring Harbor from the effects of storms that flooded and eroded the shoreline.

In 1850, they built a seawall using stones transported in three schooners from a Connecticut quarry to block water from coming ashore in what is now the picturesque coast of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, according to the booklet “Cold Spring Harbor Rediscovering history in street and shores by Terry Walton.

Time and powerful storms, including Hurricane Sandy in 2012, have taken their toll on the protective seawall, causing weaknesses that might allow future storms or water surges to damage the internationally renowned lab and the surrounding area.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory will soon start an effort to rebuild and refurbish the seawall, preserving some of its historical value by reusing original stones. The refurbishing effort, which will cost $14 million and includes $500,000 from New York State, will take 10 to 11 months to complete.

The state funds have been appropriated and are in the process of being released from the New York State Department of Budget, according to State Senator James Gaughran (D-Northport). Gaughran said he helped secure the funds and is pleased with their design.

“I applaud Cold Spring Harbor [Laboratory] for incorporating the original stones in the seawall’s restoration, which will preserve the beauty of the historic seawall,” Gaughran explained in an email.

“It’s really a feat that it lasted as long as it has,” said Stephen Monez, facilities manager at CSHL. The designers originally built the wall by stacking stones on top of each other.

“We’re starting to lose elevation of our ground,” Monez said. Utility lines for a lab where four Nobel prize winners have conducted some of their research over the years and where numerous faculty continue to conduct basic and translational research run behind the seawall, increasing the importance of the effort.

The seawall, which the Jones brothers and their Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Company built, has failed in two places, according to Errol Kitt, vice president, principal and Long Island branch manager for GEI Consultants Inc, PC. Kitt, who runs the Huntington Station office of GEI, leads the team that developed design plans for the new seawall.

A national company, GEI has worked in other areas of historical significance, including Boston Harbor.

The Cold Spring Harbor seawall is an “interesting one, with reusing the stones,” Kitt said. “That’s the new twist to this.”

Kitt helped ensure that the plans would be consistent with the concerns of regulatory agencies.

“We came up with a preliminary design that we sought buy-in from the regulatory agencies early on,” Kitt said. “That helped move the project along.”

Skanska, a Swedish-based construction and engineering group, will oversee the work, while Triumph Construction will do the construction. Kitt said the team has permits in place to start construction and is awaiting the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to finalize their permit.

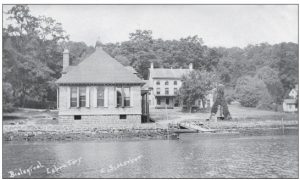

The seawall had been protecting the area for four decades in the 19th century when the Biological Laboratory of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, a predecessor to CSHL, was established in 1890.

State and local authorities, including the New York State Historic Preservation Office, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Village of Laurel Hollow, have approved the plans to rebuild the wall.

Skanska, a Swedish-based construction and engineering group, will oversee the project, while Triumph Construction, of the Bronx, will do the building work. The Huntington Station office of GEI Consultants provided the design and engineering plans.

Triumph will use concrete and rebar to rebuild a seawall that will be 2 feet higher than the original. That is the maximum additional height the lab could add. The company will clean the original and historic stones, which they will then use to reface the seawall to retain its original look.

The New York State Historic Preservation wanted to ensure that the wall “would look as original as it was before we did this project,” Monez said.

In 2014, the lab started putting money aside to rebuild the seawall. In the last 18 months, the weather has caused erosion.

“Once a wall starts to go, it doesn’t take [long] for the rest of it” to weaken, Monez said.

The facilities team at CSHL recently closed the road along the shoreline.

The seawall will be longer than the original, with the team adding more to the structure on the landward side.

CSHL has put up a 10-foot high safety fence, has added warning signs to the area and mandated a hardhat area.

Members of the facilities staff are also receiving 10 hours of training from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a regulatory agency of the U.S. Department of Labor, in case they need to enter the area.

The construction team is putting in sheet piling prior to rebuilding the seawall to protect the land while they do the work. This will prevent any damage from tidal or storm surge over the next year until the project is complete.

The first two months of the work is likely to be the loudest part of the construction process.

“We met with scientists in adjacent buildings,” Monez said.

He said the effort will provide protection for the area amid storms and any rise in the sea level.

“We are installing our insurance policy for the future,” Monez said.