By Nomi Dayan

Whaling was a risky business, physically and financially. Life at sea was hazardous. Fortunes were made or lost. Whale hunts were perilous, as was the processing of the whale. Injuries were rampant and death was common, sometimes on nearly every voyage. In some instances, the deceased was none other than the captain.

Captain Sluman Lothrop Gray met his untimely end on a whaleship. Born in 1813, very little is known of his past, his family or his early experiences at sea. In 1838, he married Sarah A. Frisbie of Pennsylvania in the rural town of Columbia, Connecticut. His whaling and navigational skills must have been precocious, because in 1842, in his late 20s, Gray became a whaling captain — and a highly successful one.

His wife Sarah joined him in his achievements, living with him at sea for 20 years. Three of their eight children were born during global whaling voyages. Gray commanded a string of vessels: the Jefferson and Hannibal of New London, Connecticut, to the Indian and North Pacific oceans; the Mercury and Newburyport of Stonington, Connecticut, to the South Atlantic, Chile, and Northwest Pacific oceans; and the Montreal of New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the North Pacific Ocean.

While financially successful, Gray’s crew felt his harsh personality left much to be desired. Some of his blasphemies were recorded by a cabin boy on the Hannibal in 1843. Gray did not hesitate to flog crew members for minor mistakes. Unsurprisingly, when Sarah once reported her husband had taken ill, the crew rejoiced. To their chagrin, he recovered.

As Gray aged, he attempted to retire from maritime living and shift into the life of a country gentleman. He bought 10 acres of land in Lebanon, Connecticut, and lived there for seven years, where his house still stands.

This bucolic life did not last, and Gray returned to whaling. With his wife and three children — 16-year-old Katie, 10-year-old Sluman Jr. and 2-year-old Nellie, he sailed out of New Bedford on June 1, 1864, on the James Maury. Built in Boston in 1825 and sold to New Bedford owners in 1845, the James Maury was a hefty ship at 394 tons. Gray steered the course toward hunting grounds in the South Pacific.

Unexpectedly, after nine months at sea in March 1865, he suddenly became ill. The closest land was Guam, 400 miles away. Sarah described his sickness as an “inflammation of the bowels.” After two days, Gray was dead. The first mate reported in the ship’s logbook: “Light winds and pleasant weather. At 2 p.m. our Captain expired after an illness of two days.” He was 51 years old.

Sarah had endured death five times before this, having to bury five of her children who sadly died in infancy. She could not bear to bury her husband at sea. Considering how typical grand-scale mourning was in Victorian times, a burial at sea was anything but romantic. It was not unheard of for a whaling wife to attempt to preserve her husband’s body for a home burial. But how would Sarah embalm the body?

Two things aboard the whaleship helped: a barrel and alcohol. Sarah asked the ship’s cooper, or barrel maker, to fashion a cask for the captain. He did so, and Gray was placed inside. The cask was filled with “spirits,” likely rum. The log for that day records: “Light winds from the Eastward and pleasant weather; made a cask and put the Capt. in with spirits.”

The voyage continued on to the Bering Sea in the Arctic; death and a marinating body did not stop the intentions of the crew from missing out on the summer hunting season.

However, there was another unexpected surprise that June: the ship was attacked by the feared and ruthless Confederate raider Shenandoah, who prowled the ocean burning Union vessels, especially whalers (with crews taken as prisoners). The captain, James Waddell, had not heard — or refused to believe —that the South had already surrendered.

When the first mate of the Shenandoah, Lt. Chew, came aboard the James Maury, he found Sarah panic stricken. The James Maury was spared because of the presence of her and her children — and presumably the presence of her barreled husband. Waddell assured her that the “men of the South did not make war on women and children.” Instead, he considered them prisoners and ransomed the ship. Before the ship was sent to Honolulu, he dumped 222 other Union prisoners on board. One can imagine how cramped this voyage was since whaleships were known for anything but free space.

A year after the captain’s death, the remaining Gray family made it home in March 1866. The preserved captain himself was shipped home from New Bedford for $11.

Captain Gray was finally buried in Liberty Hill Cemetery in Connecticut. His resting place has a tall marker with an anchor and two inscriptions: “My Husband” and “Captain S. L. Gray died on board ship James Maury near the island of Guam, March 24, 1865.” Sarah died 20 years later and was buried next to her husband.

It is unknown if Gray was buried “as is” or in a casket. There are no records of Sarah purchasing a coffin. Legend has it that he was buried barrel and all.

Nomi Dayan is the executive director at The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor.

I was truly blessed to live 12 wonderful years with great memories and milestones in Strong’s Neck. I wrote this non-fiction piece as a heartfelt thank you to a place that has so much enriched history and beautiful landscapes that, combined with my loving parents and sister, was “home.” Our new ventures take us to Queens and Manhattan. Thank you for reading.

I was truly blessed to live 12 wonderful years with great memories and milestones in Strong’s Neck. I wrote this non-fiction piece as a heartfelt thank you to a place that has so much enriched history and beautiful landscapes that, combined with my loving parents and sister, was “home.” Our new ventures take us to Queens and Manhattan. Thank you for reading.

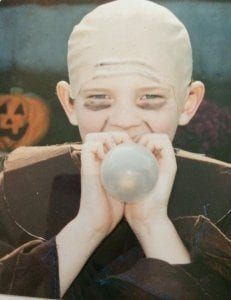

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t enamored with Halloween and, by default, horror in general. It could be argued that my birthday falling in late October has something to do with an obsession with the macabre, but I can’t help but think it goes way beyond that.

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t enamored with Halloween and, by default, horror in general. It could be argued that my birthday falling in late October has something to do with an obsession with the macabre, but I can’t help but think it goes way beyond that.