A pumped-up crowd in the Centereach High School gymnasium cheered, clapped and clamored to see which of the district’s elementary schools would come out victorious at Monday night’s STEM Celebration.

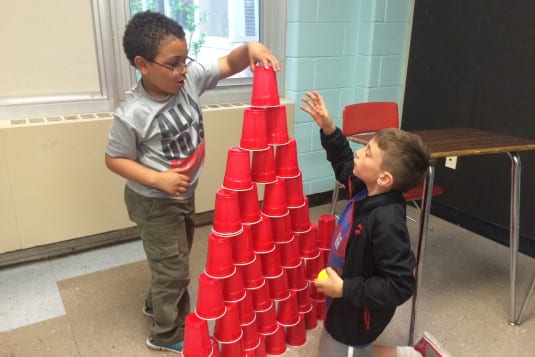

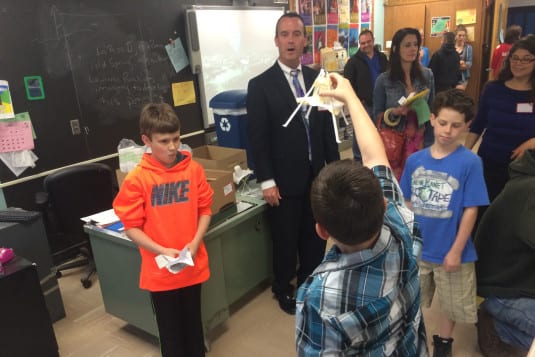

The evening marked the district’s first celebration of science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM. Hundreds of students, parents, teachers and administrators flooded the school to see students use their skills to build paper helicopters, newspaper tables and cup towers, and compete against each other to build a spaghetti tower. In addition, students from the district’s eight elementary schools presented their LEGO engineering creations to judges.

1 of 10

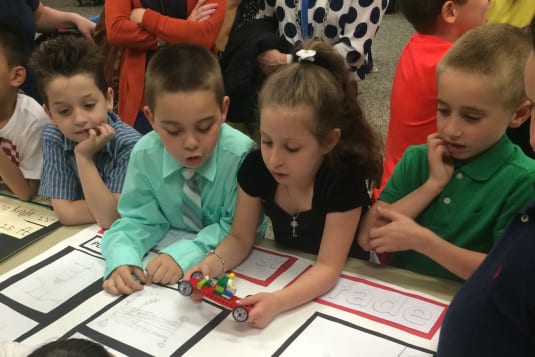

Hawkins Path Elementary students show off their LEGO Engineering creation at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

Henry Ciavarella, 7, builds a newspaper table at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

Jade Senh, 10, Gabby Fiore, 9, work together to create a “lunar lander” system, which had to keep two marshmallows, the astronauts, safe after dropping the creation. Photo by Erika Karp

Ryan Ortiz, 4, goes fishing with the fishing pole he created at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

Hawkins Path Elementary School students build a spaghetti tower using only a few materials at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

Middle country elementary school students show off their LEGO Engineering creation to a judge at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

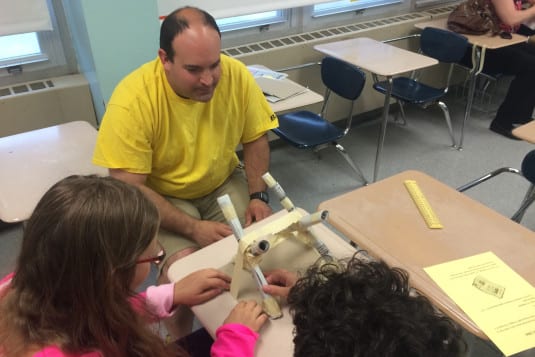

Eric Bruen, helps Cody Bruen, 10, and Natalia, 11, build a newspaper table at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp

Nick Sorrentino, 10, William Mercado, 10, successfully constructed a “Lunar Lander” at the Middle Country school district’s STEM Celebration on May 18. Photo by Erika Karp