By Matthew Kearns, DVM

I recently caught a cold from my son, Matty, and it really knocked me on my butt. Fever followed by a terrible cough that has lasted at least two weeks. The ironic part of the story is that about a week and a half into my cold, each one of my three cats developed a cough and started sneezing. My cats do not go outside and I wondered if I could give a cold to my cats.

After some investigation I couldn’t believe what I found. There are documented cases of cats with upper respiratory syndromes, and these same cats tested positive for the human H1N1 influenza virus.

I graduated veterinary school about 20 years ago, and all of the focus was on zoonotic diseases (diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans and not the other way around) or diseases that could affect herd health (say a cow that develops a respiratory disease that is either fatal or affects productivity). Through the years since I graduated, there have been smaller studies evaluating what infections we humans can give our pets. Now, there is definitive evidence that the human H1N1 influenza virus can be passed to cats.

The human-to-cat transmission of the flu is not the first time that examples of cross-species contamination has taken place. I also found examples of experimental infection of pigs with the H1N2 human influenza virus. Not only did these pigs show symptoms of the flu about four days after infection, but they also passed the disease along to uninfected pigs. More recently, the canine influenza virus outbreaks that keep making the news appear to be a mutation of an H3N8 equine influenza virus. What in the name of Sam Hill is going on?

It seems that the problem with these influenza viruses is their ability to mutate, or change their genetic sequencing. One of the better examples recently (2009) was a human outbreak in the United States where the influenza virus responsible included genetic material from North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza and a swine influenza typically found in Asia. That means this particular strain of flu virus was able to incorporate genetic material from three different species. UGH!!!!!

The most important question is this: How do we prevent this infection in our feline family members? The unfortunate dilemma with this constant mutation is there is no effective influenza virus vaccine for cats at this time. Therefore, it is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to avoid contact with your cat until at least the fever breaks. I can tell you from personal experience this is easier said than done.

My cats sleep with me, follow me around and (they’re a bit naughty) even jump on the kitchen table to see what I’m eating. The good news is that if your cat does break out with symptoms it is restricted to an upper respiratory infection.

Symptoms include lethargy, coughing, sneezing and a purulent (snotty green) discharge. If you do see a greenish discharge from the eyes or nose, antibiotics may be indicated due to a secondary bacterial infection. A much lower percentage of cats progress to a lower respiratory infection (even pneumonia). This can be quite serious and possibly fatal because it is viral and antibiotics are ineffective unless there is a secondary bacterial component.

Until a feline influenza vaccine is developed, my advice is that when you break out with the flu, good general hygiene is best even at home. If you cough or sneeze, cough or sneeze into your arm rather than cover you mouth with your hands. Make sure to regularly wash your hands or carry around the waterless hand sanitizer.

Lastly, if your cat develops signs, contact your veterinarian for advice or possibly an appointment. Good luck my fellow pet lovers.

Dr. Kearns practices veterinary medicine from his Port Jefferson office and is pictured with his son Matthew and his dog Jasmine.

Who knows when the next winter “bomb-cyclone” followed by an arctic cold front will hit Long Island. Here are a few important facts and tips to help our pets get through another winter:

Who knows when the next winter “bomb-cyclone” followed by an arctic cold front will hit Long Island. Here are a few important facts and tips to help our pets get through another winter: Arthritis affects older pets more commonly but can affect pets of any age with an arthritic condition. Cold weather will make it more difficult for arthritic pets to get around and icy, slick surfaces make it more difficult to get traction. Care should be taken when going up or down stairs and on slick surfaces. Boots, slings and orthopedic beds can be purchased from pet stores, online or through catalogs. These products will help our pets get a better grip on slick surfaces or icy surfaces and sleep better at night to protect aging bones and joints.

Arthritis affects older pets more commonly but can affect pets of any age with an arthritic condition. Cold weather will make it more difficult for arthritic pets to get around and icy, slick surfaces make it more difficult to get traction. Care should be taken when going up or down stairs and on slick surfaces. Boots, slings and orthopedic beds can be purchased from pet stores, online or through catalogs. These products will help our pets get a better grip on slick surfaces or icy surfaces and sleep better at night to protect aging bones and joints.

I had a classmate in veterinary school who simply described his cat as “good for the head.” What he meant by that statement was when the stress of classes and studying became too much he could always count on his cat to ease the burden. Well, science is backing up this claim. Having a pet in your life can be good for the head and the body.

I had a classmate in veterinary school who simply described his cat as “good for the head.” What he meant by that statement was when the stress of classes and studying became too much he could always count on his cat to ease the burden. Well, science is backing up this claim. Having a pet in your life can be good for the head and the body.

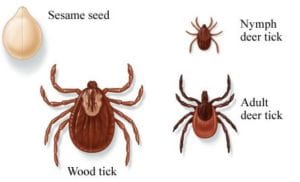

I commonly get the question, “What month can I stop using tick preventatives?” My answer is always, “That depends.” It used to be that somewhere around late October/November until late March/early April one could stop using flea and tick preventatives. However, with changing climate conditions and parasite adaptation this is no longer true.

I commonly get the question, “What month can I stop using tick preventatives?” My answer is always, “That depends.” It used to be that somewhere around late October/November until late March/early April one could stop using flea and tick preventatives. However, with changing climate conditions and parasite adaptation this is no longer true. To kill a tick temperatures must be consistently below 10°F for many days in a row. If the tick is able to bury itself in the vegetation below a layer of snow, even below 10 degrees may not kill them. It is pretty routine even in January to have one or two days that are in the 20s during the day, dropping to the teens or single digits at night followed by a few days in the 50s.

To kill a tick temperatures must be consistently below 10°F for many days in a row. If the tick is able to bury itself in the vegetation below a layer of snow, even below 10 degrees may not kill them. It is pretty routine even in January to have one or two days that are in the 20s during the day, dropping to the teens or single digits at night followed by a few days in the 50s.

I recently watched the movie “Megan Leavey” and realized that although recent events have forced many Americans to take sides on loyalty to First Amendment rights versus loyalty to the flag (as it stands for the sacrifice the military, police and rescue services make on our behalf), one belief is united: Man’s best friend has always been there for us, especially in times of war.

I recently watched the movie “Megan Leavey” and realized that although recent events have forced many Americans to take sides on loyalty to First Amendment rights versus loyalty to the flag (as it stands for the sacrifice the military, police and rescue services make on our behalf), one belief is united: Man’s best friend has always been there for us, especially in times of war.