By Heidi Sutton

Arcadia Publishing recently released “Whaling on Long Island” as part of its Images of America series. Written by Nomi Dayan, the executive director of the Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor, the book explores the impact that the whaling industry had in shaping Long Island’s maritime heritage. I recently had the opportunity to speak with Dayan about her new book and her view on the future of whales.

What made you write this book? Any more books on the horizon?

One objective in our museum’s strategic plan is to become more involved with research projects. When we were approached by Arcadia, the publisher, to put together a whaling-themed pictorial book, we jumped on the idea. I was surprised to find that there has not been a book published about Long Island’s whaling history in 50 years! There are good articles, journals and sections in other books, but no all-encompassing source for this incredible story of Long Island’s heritage. When I discussed this lack of information over dinner with my husband, he said, “Why don’t you do it?” Perhaps now is the time when we can document and share the full story of our whaling history, especially because Arcadia’s Images of America series is template-based — I was constrained by the set number of pictures and text on each page. So, I saw this book more as a beginning than as an end.

What surprised you, if anything, during the making of this book?

Finding useful photographs is, of course, a treasure, but what surprised me most was connecting with other individuals across Long Island (and beyond!) who were genuinely eager to help me tell this story — people I would likely not have met if I didn’t put this book together. Forming that network was a surprise gift! Other surprises [included] how far back whaling really goes on the Island, both with the Native Americans, as well as settlers, who started whaling almost immediately after arriving. The first commercial whaling in the New World happened on our shores! And after farming, whaling was Long Island’s first industry. I also didn’t realize how exploited Native Americans were in the beginning stages of commercial shore whaling. The Shinnecock, Montaukett and Unkechaug tribes played a fundamental role in the development of shore whaling, and it was so disheartening for me to see how quickly they became tied into seasonal cycles of exploitation and debt.

How did you go about compiling all the photographs and material for the book?

Research was like a treasure hunt! Yankee whaling and photography essentially missed each other, so I had to piece together this story in the best visual way that I could. Many of the photographs were sourced directly from the museum’s collection of 6,000 objects — and there were more images that didn’t make it in the book! Other photographs were taken from the collections of other museums and historical societies, as well as local history collections in libraries and their very helpful staff, particularly at the East End.

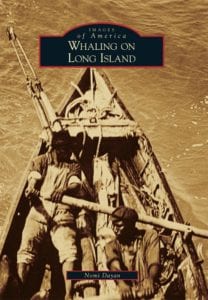

Did you get to choose the cover photo? If so, why did you choose this one?

Yes, I chose the cover photo. I felt this photo, taken by one of the museum’s founders, Robert Cushman Murphy (perhaps the foremost scientist to come out of Long Island) while aboard the Daisy [from] 1912 to 1913, showed a moment in time which was a mix of history and art. The overhead view shows the iconic image of human vs. whale, and captures the excitement, courage and drive behind venturing into the dangerous ocean to catch the largest animals on Earth. I wanted to show the whaleboat — a brilliant innovation — with its harpoons aimed forward. Will those harpoons catch a whale? Will the whale get away? Will the men return in the same shape they set out? … All we know is how hard these whalers will try, and they will risk their lives doing so. I liked how the photo shows men of color, as whaling was our country’s first integrated industry, and this photo shows how physically laborious their job was. You almost feel your arms hurt looking at them!

What kind of future do whales face? Which ones are in danger of extinction?

Whaling was one of our country’s — and planet’s — most lucrative businesses. Whale products changed the course of history. But in this process, people nearly wiped whales off the face of the Earth. Many whale species are endangered or show low population numbers, some critically, such as the North Atlantic right whale — there are only approximately 500 left! This means we have a great responsibility today — a responsibility to reflect on the repercussions of our actions, and to apply our knowledge to future decisions affecting the marine environment. Advocating for cleaner and quieter waters is saying “welcome back!” to these whales. The museum is currently installing a new exhibit, Thar She Blows!: Whaling History on Long Island which will open Oct. 2 (the opening event is called SeaFaire and is a family-friendly celebration of our maritime heritage). One aspect of this exhibit will discuss modern threats whales face, and visitors will be invited to take a pledge to help whales. One pledge will be not releasing balloons, which often end up in the ocean and can be devastating when ingested by whales and marine life. Another pledge for people who eat fish will be ensuring seafood is sustainably caught to protect healthy fish populations.

What is the whale’s biggest threat right now?

In one word — humans! Whales are facing new human-caused threats today. While commercial whaling is still a threat (Norway, Japan and Iceland defiantly kill thousands of whales annually, primarily for dietary reasons) on a global scale, there are larger threats, such as entanglement in fishing gear and ship strikes, which are serious concerns, as well as pollution — particularly plastic pollution. Many whales who are found beached have plastic in their stomachs. The ocean is also becoming noisier and noisier, which affects whale communication. Climate change, and its effect on the marine food chain, is one of the most important concerns today — changes in sea temperature, changes in food sources. Cumulatively, it’s getting harder to be a whale!

What can we do to help them?

Reducing pollution and reducing greenhouse emissions is very important. I know we may feel our actions are removed from the lives of whales, but collectively, our actions really are changing the Earth. When I went whale watching two weeks ago out of Montauk, I was so disheartened to see the floating Poland Spring plastic bottles bobbing in the ocean. We can do better. Consider using a reusable bottle! Readers should also consider the needs of the marine environment in their decision in our upcoming election. While it can take a while for populations to recover, it can happen. Humpback whales and gray whales are showing remarkable signs of population recovery, which is encouraging and inspiring. As our country’s energy needs continue to grow today, and we continue to exploit natural resources, whaling offers the timely lesson that nature is not infinite and will one day run out. We have the responsibility of applying our knowledge of whaling history to current and future decisions affecting the marine environment.

“Whaling on Long Island” is available for purchase at The Whaling Museum & Educational Center’s gift shop, Barnes & Noble and www.amazon.com.