On Saturday afternoon, Aug. 22, 1931, William Fillbach was sitting in his car, which was parked on the ferry dock at Port Jefferson, waiting to serve a warrant on a man due there at 5:30 p.m.

An investigator for the Suffolk County District Attorney, Fillbach was turning the pages of a newspaper when he caught a glimpse of a boat being hauled out of the water and on to the ways of the Port Jefferson (aka Long Island) Shipyard at the foot of Main Street.

All Fillbach could read on the vessel were the letters “Art,” but they were enough for him to identify the boat as the notorious Artemis, a rumrunner that had disappeared following her heated battle with a Coast Guard cutter.

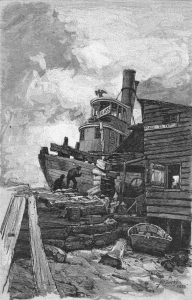

Fillbach climbed aboard the now high and dry craft, which had been moved into a shed, and carefully observed the scene. There was no contraband on the battered booze boat, but the bullet-riddled vessel was strewn with broken glass and three planks on her port side were smashed inward.

Fillbach learned that the crippled Artemis had been towed to Port Jefferson by the swordfisher Evangeline, but workers at the Port Jefferson Shipyard claimed not to know who owned the disabled craft, which bore no registration numbers, or who gave the orders to make her seaworthy.

Fearing that the mysterious smugglers might attempt to spirit the stranded Artemis out of Port Jefferson, Fillbach and five deputy sheriffs guarded the fugitive vessel until Sunday, Aug. 23, when a Coast Guard cutter took over the watch.

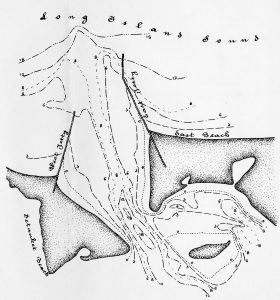

Just days before, on Thursday evening, Aug. 20, CG-808 was patrolling Long Island Sound, searching for suspected rumrunners. The cutter had sighted the 53-foot Artemis about two miles east of the Cornfield Point Lightship and commanded her to stop.

Although loaded down with illicit liquor, the speedy rumrunner answered by racing off into the darkness, propelled by her powerful Liberty aircraft engines that had been converted for marine use.

The Coasties gave chase and fired hundreds of shots at the fleeing craft, many hitting the mark. During the thick of the running battle, the agile Artemis suddenly turned about and rammed the 45-foot CG-808, forcing the severely damaged cutter to stop the pursuit and limp back to the Operating Base in New London, Connecticut.

The rumrunners then landed on the beach three miles west of Orient Point, where two badly wounded men were taken off the speedboat and driven to Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport while the vessel’s prized cargo was quickly unloaded by swarms of willing local residents.

Angered by the attack on CG-808, and miffed by the escape of the Artemis, Coast Guard officials brought in a private airplane and dispatched two patrol boats to locate the infamous rumrunner. Despite their best efforts, the Artemis was secreted away, stopping briefly in Mattituck Harbor for some patchwork before moving on to Port Jefferson for major repairs.

In the aftermath of the incident, the two crewmen who were aboard the Artemis and severely injured by gunfire from CG-808 were discharged from the hospital, both refusing to talk with the authorities.

The Artemis was seized by the United States Marshal, who claimed that her owners had an outstanding debt at the Gaffga Engine Works in Greenport. After the dispute was settled, the Artemis posted bond and quietly left Port Jefferson, much to the dismay of the Coast Guard.

Over the ensuing years, the Artemis changed hands and home ports several times, but never lost her reputation as a lawbreaker. In May 1935, the Coast Guard captured the Artemis off Chesapeake Bay and brought her to New York Harbor on suspicion of rumrunning, but without any evidence of illegality, the speedboat and her crew were released by the government.

With the end of prohibition, the Artemis began a new, but less exciting career, running as a ferry between Bay Shore and Fire Island.

In Port Jefferson, however, the Artemis will always be remembered for bringing the rum war directly to the village.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.