By Daniel Dunaief

Part 1:

A group of people may prove to be the guardian angels for the children of couples who haven’t even met yet.

After suffering unimaginable losses to a form of cancer that can claim the lives of children, several families, their foundations, and passionate scientists have teamed up to find weaknesses and vulnerabilities in cancers including rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma.

Rhabdomyosarcoma affects about 400 to 500 people each year in the United States, with more than half of those patients receiving the diagnosis before their 10th birthday. Patients who receive diagnoses for these cancers typically receive medicines designed to combat other diseases.

A group of passionate people banded together using a different approach to funding and research to develop tools for a different outcome. Six years after the Christina Renna Foundation and others funded a Banbury meeting at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the grass roots funders and dedicated scientists are finding reasons for optimism.

“I wish I could run up to the top of a hill and scream it out: ‘I’m more hopeful than I’ve ever been,’” said Phil Renna, director of operations, communications department at CSHL and the co-founder of the Christina Renna Foundation. “I’m really excited” about the progress the foundation and the aligned group supporting the Sarcoma Initiative at the lab has made.

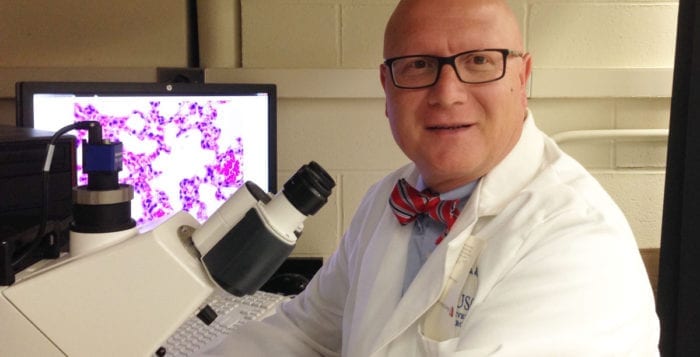

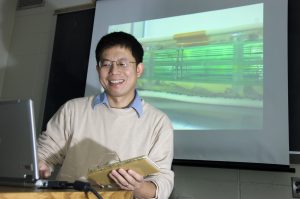

Renna and his wife Rene started the foundation after their daughter Christina died at the age of 16 in 2007 from rhabdomyosarcoma. Renna’s optimism stems from work Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s Christopher Vakoc, a professor and Cancer Center co-director and his research team, including PhD candidate Martyna Sroka have performed.

The cause for optimism comes from the approach Vakoc has taken to cancers, including leukemia.

Vakoc has developed a way to screen the effects of genetic changes on the course of cancer.

“Usually, when you hear about a CRISPR screen, you think of taking out a function and the cell either dies or doesn’t care,” Sroka said, referring to the tool of genetic editing. Sroka is not asking whether the cell dies, but whether the genetic change nudges the cellular processes in a different direction.

“We are asking whether a loss of a gene changes the biology of a cell to undergo a fate change; in our case, whether cancer cells stop growing and differentiate down the muscle lineage,” she explained.

In the case of sarcoma, researchers believe immature muscle cells continue to grow and divide, turning into cancer, rather than differentiating to a final stage in which they function as normal cells.

Through genetic changes, however, Sroka and Vakoc’s lab are hoping to restore the cell to its non cancerous state.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has had success with other diseases and other types of cancer, which is where the optimism comes from, explained Paul Paternoster, President of Selectrode Industries, Inc. and the founder of the Michelle Paternoster Foundation for Cancer Research.

As a part of her doctoral research which she’s been conducting for four years, Sroka is also working with Switzerland-based pharmaceutical company Novartis AG to test the effect of using approved and experimental drugs that can coax cells back into their muscular, non-cancerous condition.

The work Sroka and Vakoc have been doing and the approach they are taking could have applications in other cancers.

“The technology that we’ve developed to look at myodifferentiation in rhabdomyosarcoma can be used to study other cancers (in fact, we are currently applying it to ask similar questions in other cancer contexts),” said Sroka. “In addition, our findings in RMS might also shed light on normal muscle development, regeneration and the biology of other diseases that impact myodifferentiation, e.g. muscular dystrophy.”

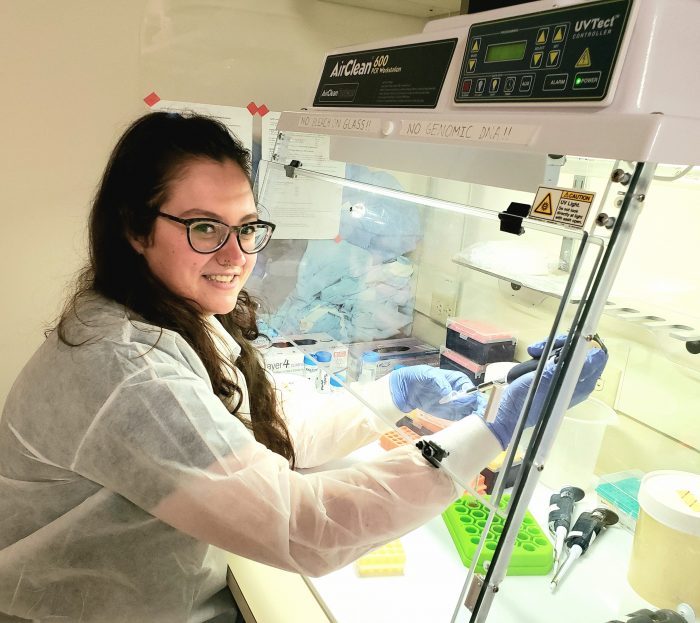

Martyna Sroka’s journey

Described by Vakoc as a key part of the sarcoma research effort in his lab, Martyna Sroka, who was born and raised in Gdańsk, Poland, came to Long Island after a series of eye-opening medical experiences.

In Poland, when she was around 16, she shadowed a pediatric oncology doctor who was visiting patients. After she heard the patient’s history, she and the doctor left the room and convened in the hallway.

“He turned to me and said, ‘Yeah, this child has about a month or two tops.’ We moved on to the next case. I couldn’t wrap my head around it. That’s as far as we could go. There’s nothing we could do to help the child and the family,” said Sroka.

Even after she started medical school, she struggled with the limited ammunition modern medicine provided in the fight against childhood cancer.

She quit in her first year, disappointed that “for a lot of patients diagnosed with certain rare types of tumors, the diagnosis is as far as the work goes. I found that so frustrating. I decided maybe my efforts will be better placed doing the science that goes into the development of novel therapies.”

Sroka applied to several PhD programs in the United Kingdom and only one in the United States, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where she hoped to team up with Vakoc.

Sroka appreciated Vakoc’s approach to the research and his interest in hearing about her interests.

“I knew that we could carve out an exciting scientific research project that tries to tackle important questions in the field of pediatric oncology, [the] results of which could potentially benefit patients in the future,” she explained in an email.

The two of them looked at where they could make a difference and focused on rhabdomyosarcoma.

Sroka has “set up a platform by which advances” in rhabdomyosarcoma medicines will be possible, Vakoc said. “From the moment she joined the sarcoma project, she rose to the challenge” of conducting and helping to lead this research.

While Sroka is “happy” with what she has achieved so far, she finds it difficult at times to think about how the standard of care for patients hasn’t changed much in the last few decades.

“Working closely with foundations and having met a number of rhabdomyosarcoma patients, I do feel an intense sense of urgency,” she wrote.

Read Part 2 here.