Ferdinand Magellan didn’t have the luxury of sending a machine into the unknown around the world before he took to the seas. Modern humans, however, dispatch satellites, rovers and orbiters into the farthest reaches of the universe. Several months after the New Horizons spacecraft beamed back the first close-up images of Pluto from over three billion miles away, NASA confirmed the presence of water on Mars.

The Mars discovery continues the excitement over the possibility of sending astronauts to the Red Planet as early as the 2030s.

Before astronauts can take a journey between planets that average 140 million miles apart, scientists need to figure out the health effects of prolonged exposure to damaging radiation.

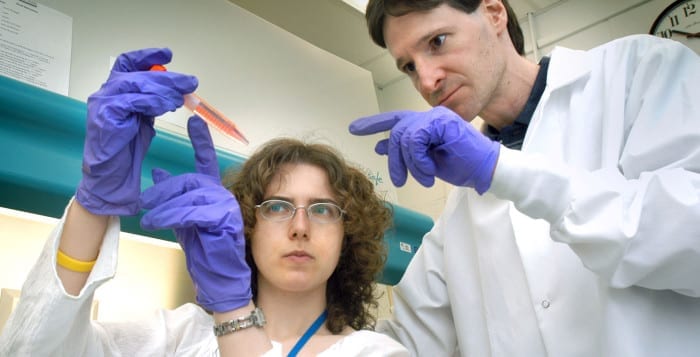

Each year, liaison biologist Peter Guida at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) at Brookhaven National Laboratory coordinates the visits of over 400 scientists to a facility designed to determine, among other things, what radiation does to the human body and to find possible prevention or treatment for any damage.

Guida is working to “improve our understanding of the effects that space radiation from cosmic rays have on humans,” explained Michael Sivertz, a physicist at the same facility. “He would like to make sure that voyages to Mars do not have to be one-way trips.”

Guida said radiation induces un-repaired and mis-repaired DNA damage. Enough accumulated mutations can cause cancer. Radiation also induces reactive oxygen species and produces secondary damage that is like aging.

The results from these experiments could provide insights that lead to a better understanding of diseases in general and may reveal potential targets for treatment.

This type of research could help those who battle cancer, neurological defects or other health challenges, Guida said.

By observing the molecular changes tissues and cells grown in the lab undergo in model systems as they transition from healthy to cancerous, researchers can look to protect or restore genetic systems that might be especially vulnerable.

If the work done at the NSRL uncovers some of those genetic steps, it could also provide researchers and, down the road, doctors with a way of using those genes as predictors of cancer or can offer guidance in tailoring individualized medical treatment based on the molecular signature of a developing cancer, Guida suggested.

Guida conducts research on neural progenitor cells, which can create other types of cells in the nervous system, such as astrocytes. He also triggers differentiation in these cells and works with mature neurons. He has collaborated with Roger M. Loria, a professor in microbiology and immunology at Virginia Commonwealth University, on a compound that reverses the damage from radiation on the hematological, or blood, system.

The compound can increase red blood cells, hemoglobin and platelet counts even after exposure to some radiation. It also increases monocytes and the number of bone marrow cells. A treatment like this might be like having the equivalent of a fire extinguisher nearby, not only for astronauts but also for those who might be exposed to radiation through accidents like Fukushima or Chernobyl or in the event of a deliberate act.

Loria is conducting tests for Food and Drug Administration approval, Guida said.

If this compound helps astronauts, it might also have applications for other health challenges, although any other uses would require careful testing.

While Guida conducts and collaborates on research, he spends the majority of his time ensuring that the NSRL is meeting NASA’s scientific goals and objectives by supporting the research of investigators who conduct their studies at the site. He and a team of support personnel at NSRL set up the labs and equipment for these visiting scientists. He also schedules time on the beam line that generates ionizing particles.

Guida is “very well respected within the space radiation community, which is why he was chosen to have such responsibility,” said Sivertz, who has known Guida for a decade.

Guida and his wife Susan, a therapist who is in private practice, live in Searingtown.

While Guida recalls making a drawing in crayon after watching Neil Armstrong land on the moon, he didn’t seek out an opportunity at BNL because of a long-standing interest in space. Rather, his scientific interest stemmed from a desire to contribute to cancer research.

When he was 15, his mother Jennie, who was a seamstress, died after a two-year battle with cancer. Guida started out his career at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where he hoped to make at least the “tiniest contribution” to cancer research.

He pursued postdoctoral research at BNL to study the link between mutations, radiation and cancer.

Guida feels as if he’s contributed to cancer research and likes to think his mother is proud of him. “Like a good scientist,” though, he said he’s “never satisfied. Good science creates the need to do more good science. When you find something out, that naturally leads to more questions.”