By Daniel Dunaief

In a wide-ranging interview, Louise Leakey, Director of Public Education and Outreach for the Turkana Basin Institute and a Research Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Stony Brook University shared her thoughts on numerous topics in the field of paleontology.

Leakey, who earned her PhD at the University College London, suggested that the process of finding fossils hasn’t changed that much, although other options beyond scouring a landscape for fragments of the world’s former occupants may be forthcoming.

“It may very well change if we can implement machine learning with high resolution imagery, using drones,” she said. “That’s one of the things we’re looking at the moment.”

What’s really changed, however, is the accuracy field scientists have in marking where, and, importantly, when new discoveries originated, she said.

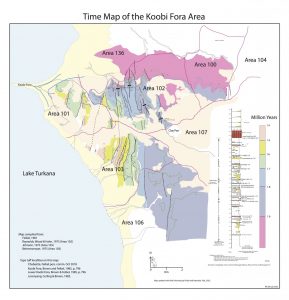

Geologists like Bob Raynolds, Research Associate at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, have created time maps that indicate the approximate age of sediments around a fossil in some select areas of the Turkana Basin.

These maps “can be uploaded onto an iPad app for use in the field that shows you in real time where you are on the geological map,” Leakey explained. “This is a game changer for field work in the basin.”

The maps represent the work of many people, Raynolds explained. Originally, teams of Master’s students used air photographs, tracing paper and ink to make a map. These students spent many weeks walking systematically on the ground and tracing the patterns on the photos.

The rugged and isolated nature of the ground in Northern Kenya makes the work done on foot difficult, Raynolds explained.

The original maps, which were made in the 1970’s, took months to make and were presented as paper copies in unpublished Master’s theses. After numerous enhancements, Raynolds, working with companies including Geologic Data Systems in Littleton, Colorado, created time maps.

The internal GPS on an iPhone enables a blue dot to indicate a person’s location on the map.

“I have worked on the maps to make a new set of derived products that are maps of the age of the rocks,” said Raynolds who created these time maps earlier this year. “The resolution of the time maps is 100,000 years” which is an “astonishingly detailed resolution for us who are accustomed to million year packages of time.”

The maps cover the entire Turkana Basin at various scales, Raynolds added.

More broadly, Bernard Wood, University Professor of Human Origins in the Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleontology at George Washington University and the first speaker at a recent Stony Brook University conference to honor Richard Leakey, explained that dating fossils has become increasingly accurate.

The first dates of fossils in the KBS Tuff, which is an ash layer in the Koobi Fora Formation east of Lake Turkana, was estimated within 260,000 years of a specific date. Using improved methods, a study published this year has reduced that range to 600 years.

Publishing pace

In the meantime, the pace of publishing has slowed considerably.

“There’s so much more material” that can serve as a frame of reference for new discoveries, Leakey said. “The rate of publication is frustratingly slow for some of these specimens.” This contrasts dramatically with the experience of Leakey’s father Richard.

When the elder Leakey submitted his letters or paper to the prestigious journal Nature, the late editor John Maddox never sent them out for review. “[Maddox] explained that he couldn’t see the point, because they concerned fossils so recently discovered” that few had seen them, Wood explained in his presentation.

Louise Leakey also differed from Richard in earning her bachelor’s degree and PhD, while her father dropped out of high school and never received any additional formal education.

Wood suggested that, next to marrying Meave, the elder Leakey described leaving school as one of the best decisions he’d ever made.

For his daughter, though, Leakey “encouraged me to go and do that,” Louise Leakey said. The education helped “in terms of being able to be [principal investigator] on grant applications,” she said.

Leakey suggested it was a “real privilege to be able to spend time” earning her PhD. She also found that the educational experience gave her the opportunity to “stand on my own two feet” in her research.

Like her father, Louise Leakey is concerned about conservation and declining biodiversity. When she was younger, she saw areas that were teeming with wildlife. On a recent three-hour drive, she only saw a golden jackal and a dik-dik, which is a type of small antelope, compared with the much wider variety of creatures she would have seen decades ago, such as Grévy’s zebra, Burchell zebra, lesser kudu, ostriches, warthogs, topi, gerenuk, oryx and, possibly lions and cheetah.

She attributes this decline to hunting as some have exterminated these species as result of competition for grazing areas and hunting the animals for meat. Record droughts are also threatening their survival.

Leakey is working with the next generation to get “kids to care about nature” so they can “think about what they’re doing and the real impact it has.”

In addition to preserving biodiversity, Leakey remains passionate about studying the past, which could help the current and future generations tackle climate change. “We might be able to learn lessons” from those who survived during such challenging conditions, she said.

Leakey is able to maintain her involvement and commitment to numerous efforts by working with talented collaborators.

“If you don’t have teams to really hold it together, you can’t do any of it,” she said.