By John L. Turner

This is the first of a two-part series.

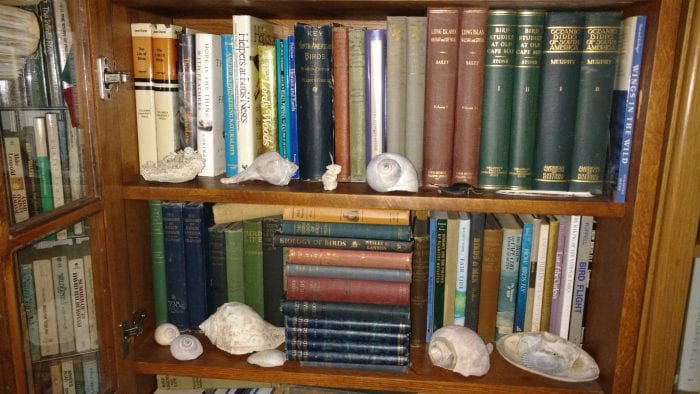

Like most people I’ve always liked to collect things. Some objects were mainstream — baseball cards and comic books as a kid, for example, but some were decidedly not. As an adult I’ve had a prolonged passion for old bird books dating from the end of the nineteenth century through the beginning of the twentieth.

Looking around my study from where I write this, I realize I have a lot of objects that fit the latter “non-mainstream” category — deer antlers, assorted shells and other marine objects, mammal skulls, numerous pine cones, and a bird nest or two lying scattered along the leading edge of the shelves that hold the beloved bird books.

I also realize these objects, collected from countless outdoor explorations, represent a window to the world of nature that lays accessible on the other side of each of our front doors.

I’ve especially liked to collect items found along the shore, of which we have a lot. I have a favorite piece of driftwood, its edges rounded and softened from years in the elements. In it sits two species of whelk shells — Knobbed and Channeled Whelk, both species of sea snails native to Long Island’s marine waters.

Knobbed Whelk gets its name from knobs or projections that lay along the coil situated on the top of the shell; the Channeled Whelk’s name comes from a coiled channel or suture that runs along the inside edge of the spiral. These two species are closely related, belonging to the same genus; sometimes referred to as conch, they are the source of scungilli, the Italian dish especially popular around the holidays.

If you spend anytime strolling along the shoreline of Long Island Sound you’ve probably seen further evidence of whelk — their tan-colored egg cases washed up in the wrack line. Complex objects they are, consisting of upwards of a dozen or more quarter-sized compartments, connected by a thread, reminiscent of a broken Hawaiian lei.

If you find an egg case shake it vigorously; if it sounds like a baby’s rattle you’ll be rewarded by opening up one of the leathery compartments, because the objects causing the sound are many perfectly formed, tiny whelks.

As I recently found out, you can identify the whelk species by the shape of the egg case compartments — Channeled have a pinched margin like what a chef does to a dumpling while the margins of Knobbed have an edge like a coin. How an adult whelk makes this highly complex structure with several dozen baby whelks in each unit is a complete mystery to me.

On the shelf next to the driftwood is another egg case — this one from a skate and, as with whelk egg cases, it’s often found as an item deposited in the beach’s wrack line. Black, with a shine on its surface, it is rectangular with four parentheses-like projections sticking out from the four corners. Skates, related to sharks, are distinctive shaped fish with “wings” and several species are found in the marine waters around Long Island including Winter, Barndoor, and Little Skates.

The cases are sometimes called “mermaids purses,” a wonderfully colorful name, although I’ve never seen any items a mermaid would carry inside one. If you look closely you can see the broken seam, along one of the shorter edges, where the baby skate emerged.

The distinctive shell of Northern Moon Snails are another common item found by beachcombers and a common item on my shelf — with four prized specimens, including the largest I’ve ever seen, they are the second-most common item I have. (Various pinecones are the most common but that’s for a future column).

Moon snails are shellfish predators, possessing a massive foot that’s 3x to 4x the size of the shell when it spreads out that it uses to push through sand. If you’ve ever picked up a clam or mussel shell with a round little hole through it you’ve just picked up a Moon Snail victim. They use a specialized “tongue” called a radula to rasp their way into the shell of a bivalve. Once through the shell, the snail secretes a weak acid that helps dissolve the tissue of the clam or mussel which the snail slurps up.

Twice while beach combing I’ve found other evidence of a Moon Snail — a sandy, semi-circular collar made of sand grains held together by gluelike mucus the snail secretes. These are egg masses, an intact one shaped like a nearly closed letter “C” (the two I found were half of that as they are fragile and easily broken). Each collar contains scores of snail eggs which develop and hatch if not predated by smaller snails like oyster drills and periwinkles.

Rounding out the discussion of my study’s marine objects are two other shells: Jingle Shells and Slipper Shells — the first a bivalve, the second a species of snail. Jingle shells, get their name from the jingling sound they make if you shake a few together in your hand and are used to make wind chimes you’ll sometimes see hanging from beach houses. They are beautiful and iridescent, coming in several different colors — orange, yellow, white, and grey. Jingle shells are also known as “mermaid’s toenails.”

Slipper shells are also fascinating animals. All slipper shells start off as male but as they mature they become female. They often stack with the larger females on bottom and the smaller males on top, making the species a “sequential hermaphrodite.” Occasionally you’ll see a slipper shell attached to a horseshoe crab. These gifts and others await you on a stroll along Long Island’s hundreds of miles of shoreline.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.