Reviewed by Leah Chiappino

Many Long Islanders have come to think of the former state psychiatric hospitals as mere eyesores, or frankly nuisances, as they are often sites for horror seekers and rebellious teenagers to trespass. However, as told by Joseph M. Galante, a former state hospital worker, in his new book “Long Island State Hospitals,” the mental health facilities were once practically their own metropolis. The book is a part of the Images of America series from Arcadia Publishing.

In the late 1800s, the city of New York transferred a few dozen patients to what was then called the St. Johnland farm colony, in hopes they would benefit from an outdoor experience. Another facility was opened in Central Islip, and in 1931 Pilgrim State was constructed to house the growing population of the mentally ill on Long Island.

The intake grew so large that Pilgrim State holds the record for the world’s largest psychiatric facility, with nearly 15,000 patients by 1955. Galante states the hospital’s principles focused on moral therapy, and they are “remembered for their legacy of humility, beneficence and a devotion to the mentally ill.” He assures readers practices like electrotherapy were only used in extreme cases, contrary to the commonly held belief that the patients were treated inhumanely.

This seems to be true from the beginning of its history. The St. Johnland facility had its name changed to Kings Park in 1891 and in 1898 graduated its first class of nurses. By then, each hospital had many independent medical surgical buildings, stores, powerhouses, a full-scale farm and ward buildings. The institutions became so self-sustainable that they produced as much as two-thirds of the food consumed there.

The Kings Park facility even had what they called York Hall, where patients would watch movies, play basketball, perform shows and attend functions. The facility also had its own water tower, railroad station, space for masonry work, independent fire and police force and the Veterans Memorial Hospital, which was a group of 17 buildings used to treat veterans that came home from World War I with mental conditions.

The Kings Park facility even had what they called York Hall, where patients would watch movies, play basketball, perform shows and attend functions. The facility also had its own water tower, railroad station, space for masonry work, independent fire and police force and the Veterans Memorial Hospital, which was a group of 17 buildings used to treat veterans that came home from World War I with mental conditions.

The staff at Kings Park provided 24-hour care to patients and worked 12-hour days, 6 days a week prior to the start of the 20th century. Men earned between $20 and $40 a month, while women earned between $14 and $18. They were granted uniforms, rubber coats and boots, food, laundry services, lodging and “chicken and candy every Sunday.”

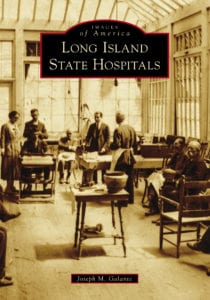

Patients were encouraged to work within the facility, but were not forced. When they were not working, they engaged in social and recreational events, as well as attended medical clinics and occupational and psychiatric therapies. Up until the 1940s, there was an emphasis on dance, music, art and cooperative activities as a form of therapy.

Ultimately, the book shows a refreshing portrait of three institutions that were such an instrumental part of Long Island’s history. Pictures range from the 1925 Kings Park Fireman Squad to a heartwarming photo of nurses at Central Islip celebrating the 105th birthday of a woman with no family who received no visitors for decades.

There are also many photos of recreational activities, including a holiday celebration for patients wearing party hats, which masks the ominous bars on the window in the background.

Anyone who has ever driven around the Nissequogue River State Park, and has a feeling of curiosity about what was once there should without fail pick up the book, which provides a productive answer to curiosity, without the reader breaking a trespassing ordinance.

“Long Island State Hospitals” is available locally where books are sold and online at www.arcadiapublishing.com.

Images courtesy of Arcadia Publishing