By Daniel Dunaief

What if dentists could see developing cavities earlier? What if, once they discovered these potential problems, they could help their patients protect their teeth and avoid fillings? And, to top it off, what if they could do this without exposing their patients to radiation from X-rays?

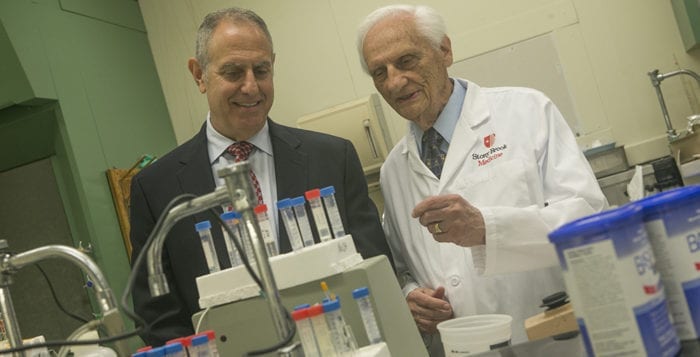

That’s exactly what Israel Kleinberg, a longtime Stony Brook University dental researcher and the founding director of the Division of Translational Oral Biology at SBU, recently developed. Called the electronic cavity detector, this new tool was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The device monitors mineral loss in enamel of molars and premolars. Powered by a battery, the handheld ECD uses electrical conductance to diagnose and monitor lesions. Tooth enamel does not conduct a signal. A lesion or crack in the enamel, however, will allow the ECD to record an early indication of a developing cavity.

“The ECD can detect lesions that are microscopic and [detect them] much sooner than X-rays,” Kleinberg explained in an email. Other research has shown that “X-rays are not very effective for diagnosing incipient enamel caries [cavities], though the technique is very useful for diagnosing deeper lesions.”

Ortek Therapeutics, a small company based in Roslyn Heights, supported the research to develop the technology over the last 10 years. Ortek is developing plans to commercialize the ECD, which could be available at a neighborhood dentist’s office by the middle of next year.

Mitch Goldberg, the president of Ortek, said the response to a positive reading on the ECD will depend on the dental practitioner. A very low conductance number could suggest a dentist pay further attention to the specific tooth. It might also lead a dentist to suggest improving oral care, brushing better or prescribing a fluoride rinse, among other options.“If the number is higher, the dentist will decide the appropriate treatment option, which could include minimally invasive procedures,” Goldberg said.

Goldberg, whose firm invested over $1 million in the work, is excited about the prospects for the ECD, for which Ortek filed and received a patent and then went through the FDA approval process. “It’s a painless” way to monitor teeth, Goldberg said. “There’s no radiation [involved].”

To be sure, he said the ECD won’t replace X-rays, particularly for teeth that already have a crown or other dental work or that are already known to have cracks or fissures. Still, Goldberg said this device could help monitor back teeth, where tiny lesions would not be causing a patient pain. The examination itself will require a short exam by either a hygienist or a dentist, who can put a probe in the bottom of a groove and gently move it along the tooth.

Any dental professional could be “trained on this in about 15 minutes,” Goldberg said. “They do similar types of work when they are probing and cleaning” teeth. Practitioners would likely understand the approach quickly, he said.

To operate the device, a dentist places a lip hook in the patient’s mouth. The dentist then puts a cotton roll between the tooth and the cheek, then air dries the tooth, Kleinberg explained in an email. The dentist lightly touches the tooth with the ECD probe and testing is completed in seconds.

Kleinberg, who has been developing this device for 14 years, suggested that the most common potential causes of false readings might be failure to dry the surface and operator error. The researcher developed this product with Stony Brook University Research Assistants Robi Chatterjee and Fred Confessore.

The partnership with Stony Brook has been a “win-win” for Ortek. Indeed, Kleinberg also developed a product called BasicBites. The chewable BasicBites provide a pH environment that supports healthy bacteria in the mouth. At the same time, BasicBites makes it harder for the bacteria that eats sugars and produces acids that wear away minerals on teeth to survive. The product make it tough for the acid-producing bacteria to eat food leftovers stuck between or around teeth.

Kleinberg, who has been with Stony Brook for 44 years, still works full time and shows no signs of slowing down. The researcher is the founding chairman of the Department of Oral Biology and Pathology. He stepped down from that position in 2009. Goldberg said he speaks with Kleinberg several times a week and calls his partner in cavity fighting an “inspiration,” adding that Kleinberg is considered the grandfather of oral biology.

Goldberg said he has a great sense of satisfaction when he goes to a pharmacy. “I take a glance at some of the products on store shelves that came out of Stony Brook and Ortek and it does give me tremendous pride,” he said.

Goldberg said he can’t disclose the market size for the ECD. He added that there are over 100,000 general dentists in the country who treat people of all ages. “There’s a tremendous opportunity for us,” he said, suggesting that dentists could check for any signs of early tooth decay before putting on a sealant.

Taking a similar approach to the BasicBites work, Kleinberg, with support from Ortek, is also researching skin-related technology for fighting MRSA-related infections and body odor. Goldberg said unwelcome bacteria often contribute to unpleasant smells that come off the skin. Ortek is also promoting the growth of healthy bacteria that reduce those scents.

While still in the early stages of development, Kleinberg has “developed a patented cutaneous or skin microbiome technology that promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria while crowding out harmful microbes,” Goldberg said. By exploring the microbiome, Kleinberg can promote the growth of better bacteria in the feet and under the arms.