By Daniel Dunaief

Two Stony Brook University researchers are helping a team of scientists rewrite the timeline of modern humans in Europe.

Prior to a ground breaking study conducted in the Rhône Valley in a cave called Grotte Mandrin in southern France, researchers had believed that homo sapiens — i.e. earlier versions of us — had arrived in Europe some time around 45,000 years ago.

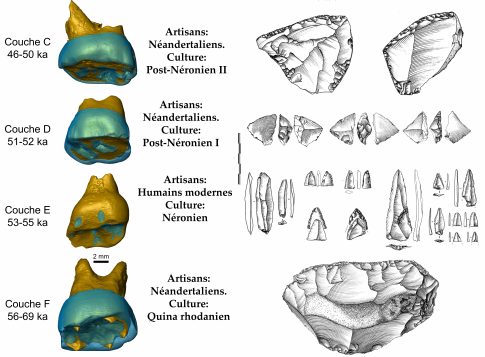

Scientists had been studying the stone tools in this cave for close to 30 years that seemed inconsistent with the narrative that Neanderthals had exclusively occupied Europe at that point. Researchers found key evidence in this cave, including advanced tools and teeth that came from modern humans, that pushed the presence of modern humans back by about 10,000 years to about 56,800 years ago, while also indicating that the two types of humans interacted in the same place.

“This is a huge paradigm shift in our understanding of modern human origin expansion,” said Jason Lewis, a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at Stony Brook University and Assistant Director at the Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya. “We can demonstrate that it was modern humans. We have a whole series of radiometric dates to shore that up 100 percent. Any method that was useful was applied” to confirm the arrival of homo sapiens in southern France.

Ludovic Slimak, CNRS researcher based at the University of Toulouse Jean Jaures, is the lead author on a 130-page paper that came out this week in Science Advances. Slimak has been exploring a site for 24 years that he describes as a kind of Neanderthalian Pompei, without the catastrophe of Mount Vesuvius erupting and preserving a record of the lives the volcano destroyed.

“This is a major turn, maybe one of the most important since a century,” Slimak explained in an email.

The early Homo sapiens travelers left behind clues about their presence in a rock shelter that alternately served as a home for Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the same year.

“We demonstrate in our paper that there is less than a year, maybe a season (six months), maximal time between the last Neanderthal occupation in the cave and the first Sapiens settlement,” Slimak wrote. “This is a very, very short time!”

The scientists came to this conclusion after they developed a new way to analyze the soot deposits on the vault fragments of the cave roof, he added.

When modern humans arrived in the Rhône Valley, they likely turned to Neanderthals, who had occupied the area considerably longer, as scouts to guide them, Slimak suggested.

Homo sapiens likely traveled by boat to France at the same time that other Homo sapiens journeyed over the water to Australia, between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

“We know that when Mandrin groups reached western Europe, Eurasian populations perfectly master navigation at the other end of the continent,” Slimak explained in an email. “It is then very likely that these technologies were at this time period well known by all these populations.”

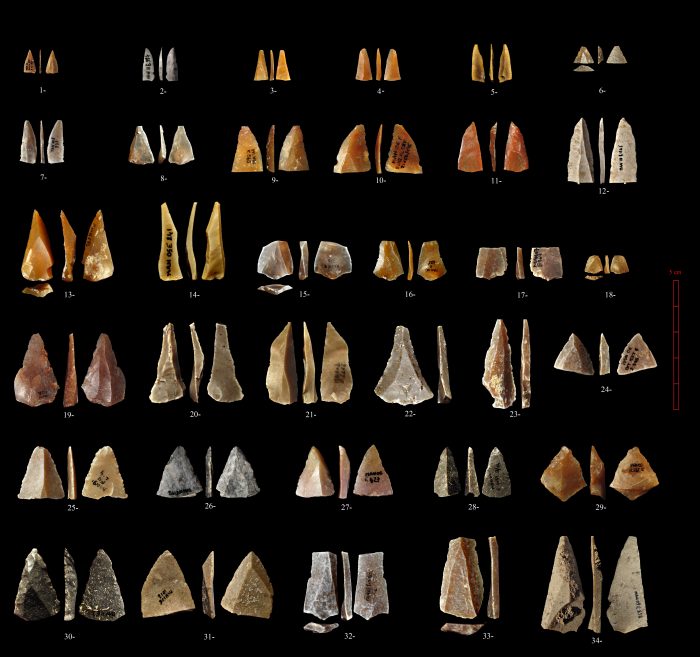

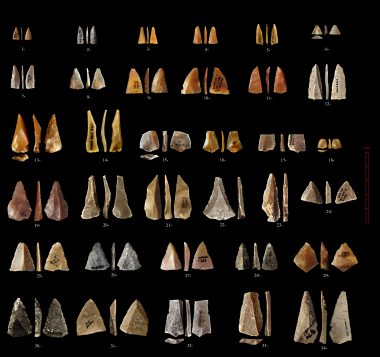

Different tools

In addition to fossils, scientists have focused on the tools that Homo sapiens produced and used. Homo sapiens likely used bows or spears with mechanical propulsion, while Neanderthals had heavy hand-cast spears, Slimak explained.

The modern human technology was “very impressive,” Slimak added. They are exactly the same technologies we found in the eastern Mediterranean at the very beginning of the Upper Paleolithic in the same chronology [as] the Grotte Mandrin.”

The tools were small and pointed and looked like the kind of arrowheads someone might find when hiking along trails on Long Island, Lewis described. “It’s never been suggested or demonstrated that Neanderthals made bows and arrows or complex projectiles,” he said.

Once they discovered teeth of Homo sapiens, the researchers found the conclusive fossil proof of “who was there doing this,” Lewis said. “Even on a baby tooth, you can distinguish Neanderthals from modern humans.”

While researchers have excavated other caves in the Middle Rhône Valley region, they have not used such stringent methods, Lewis explained. “Mandrin is truly unique for the vision it gives us into this period of the past,” he explained in an email. He described Mandrin as more of a rock shelter than a cave, which is about 10 meters wide and eight meters deep.

The importance of timing

With the importance of providing specific dates for these discoveries, scientists who specialize in ancient chronology, such as Marine Frouin, joined the team.

Frouin, who started working in the Grotte Mandrin in 2014 when she was a post-doctoral fellow at the Luminescence Laboratory at the University of Oxford, looks for the presence of radioactive elements like potassium, thorium and uranium to determine the age of sediments. When these elements decay, they emit radiation, which the sediments accumulate.

Frouin likened the build up of radioactive elements in the grains to the process of charging a battery. Over time, the radioactive energy increases, providing a signal for the last time sunlight reached the sediment.

Indeed, when the sun reaches these grains, it eliminates the signal, which means that Frouin collected samples in lower light, transported them to a lab or facility in darkness, and then analyzed them in rooms that look like a photographer’s darkroom studio.

Frouin conducted the first of three approaches to determining the timing for these discoveries. She used luminescence on quartz, feldspar and flint and was the first one to obtain dates in 2014. Colleagues at the Université de Paris then conducted Thermoluminescence dating on burnt flint, while the lab of Andaine Seguin-Orlando at the University Paul Sabatier Toulouse 3 provided single grain dating.

The three labs “were able to combine all our results together and propose a very precise chronology for this site with very high confidence,” she explained in an email.

Frouin, who arrived at Stony Brook University in January of 2020, has designed and built her own lab, where she plans to study samples and advance the field of luminescence dating.

At this point, luminescence dating can provide the timing from a few hundred years ago to 600,000 years, beyond which the radioactive signal reaches its maximum brightness. Trained as a physicist, Frouin, however, is developing new techniques to find larger doses from grains that data at least over a million years old.

Journey to France

During this period of time on the Earth, the climate was especially cold. That, Lewis said, would favor the continued use of the cave by Neanderthals, who could have survived better under more challenging conditions.

At around 55,000 years ago, however, something may have shifted in the modern human population that allowed Homo sapiens to survive in a colder climate. These changes could include projectile weapons, more advanced clothing and/or social cooperation.

“These are all hypotheses we are dealing with,” Lewis said. “In this case, it seems like a tentative exploration by modern humans into Western Europe.”

The cave itself would have been especially appealing to Neanderthals or modern humans because of its geographic and topological features. For scientists, some of those same features also helped provide a chronological record to indicate when each of these groups lived in that space.

Near the cave, the Rhône River provides a way to travel. The cave itself is situated at a bottleneck through which groups of migrating animals such as horse, bison and deer traveled to follow their own food sources.

“It’s one of the most strategic points in Southern France,” Lewis said.

Indeed, Allied Forces during World War II recognized the importance of this site, landing in Provence on August 15, 1944. The progression into Europe mirrored the expansion of modern humans, said Lewis, who studies history and is particularly interested in WWII.

The site faces northwest in a part of the Rhône Valley in which the mistral wind, which is a cold and dry strong wind, can reach up to speeds of 60 miles per hour. During the glacial period, the wind blew dust that came off the tundra of northern Europe, filling the cave with fine grain sediment that helped preserve the site. Using that dust, scientists determined that Neanderthals had occupied that cave for almost 100,000 years. Around 55,000 years ago, modern humans showed up, who were replaced again by Neanderthals.

A resident of Stony Brook, Lewis lives with his wife Sonia Harmand, who is in the same department at Stony Brook and with whom he has collaborated on research, and their daughter Scarlett.

A native of Dover, Pennsylvania, Lewis decided to study evolution after reading a coffee table book at a friend’s house when he was 13 that included descriptions of the work of the late paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey. After reading that book, Lewis said evolution made sense to him and he was eager to participate in the search for evidence of the changes that led to modern humans.

His first field experience was in a Neanderthal site in France, where he also traveled to the Turkana basin in Kenya for a project directed by Rutgers University. Ultimately, he wound up working for Rutgers and has conducted considerable research in Kenya as well.

“After working at Rutgers, I came to Stony Brook to work for [Richard Leakey in a field school at [what would become] the Turkana Basin Institute,” he said. The combination of his earlier aspirations to join Leakey, his first research field experiences including time in France and Kenya, and his eventual work with Leakey and his role at TBI were a part of his “circle of life.”

Lewis is thrilled to be a part of the ongoing effort to share information discovered in a cave he called a “magical place. The satisfaction at being there is high.”

For Slimak, the years of work at the site have been personally and professionally transformational. After taking necessary breaks from the rigors of excavating on the cave floor, he is now more comfortable sleeping on a hard floor than on a soft mattress.

Professionally, Slimak described this paper as the culmination of 32 years of continuous scientific efforts, which includes a “huge amount of very important unpublished data” that include social, cultural, economic and historical organization of these populations.

The current paper represents “only the visible part of the iceberg and many important enlightenment and other fascinating discoveries from my team will be made available in the coming months and years.”

A tough beginning

A native of Bordeaux, France, Frouin had a tough start to her work at Stony Brook. She arrived two months before the pandemic shut down many businesses and services, including driving schools and social security offices.

When she arrived, she didn’t have a driver’s permit or a credit history, which meant that she relied on the kindness and support of her colleagues and transportation from car services to pick up necessities like groceries.

A resident of Port Jefferson, Frouin, who enjoys playing electric guitar and does oil painting when she’s not studying sediments, said it took just under a year to get her American driver’s license.

Frouin, who has an undergraduate and a graduate student in her lab and is expecting to add another graduate student soon, appreciates the opportunity to explore the differences between the north and south shore of Long Island.

As for her contribution to this work, she said this effort was “extremely exciting. I’m doing what I wanted to do since I was a kid. We were able to answer many questions that maybe 20 years ago, we weren’t able to answer.”