After the Long Island Rail Road brought a branch to Northport in 1868, a group of prominent Port Jefferson businessmen lobbied for extending the north shore branch eastward to their village.

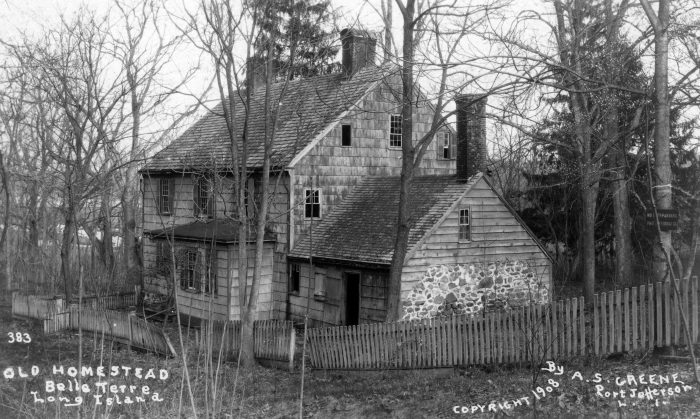

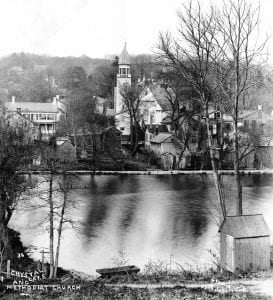

Although a leading wooden shipbuilding center in the years following the Civil War and blessed with one of the finest harbors on Long Island, Port Jefferson was surprisingly isolated for so important a village.

Going to New York City by train involved a tedious stage ride from Port Jefferson to Medford, the nearest station on the LIRR’s main line, followed by a rail trip to Long Island City and a ferry run across the East River to James Slip in Manhattan.

Port Jefferson Harbor often froze over during the winter and limited travel by packets, steamboats and other vessels engaged in waterborne commerce.

Hoping to make Port Jefferson more accessible and boost its economy, a committee of villagers was formed and charged with inducing the LIRR to bring freight and passenger service to Port Jefferson.

The diverse group included realtor William Fordham, publisher Harvey Markham, druggist Holmes Swezey, and tinsmith John Lee. They met regularly from 1868-1870 with representatives from St. James, Setauket, Stony Brook, and other communities where support for extending the Northport branch was strong.

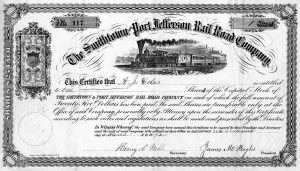

Following lengthy discussion, a proposal was submitted to and accepted by the LIRR. The Smithtown and Port Jefferson Rail Road Company, organized in 1870, pledged to raise the money necessary to construct the 18-mile extension from Northport to Port Jefferson. Upon completion of the project, the LIRR agreed to lease and operate the franchise for 20 years.

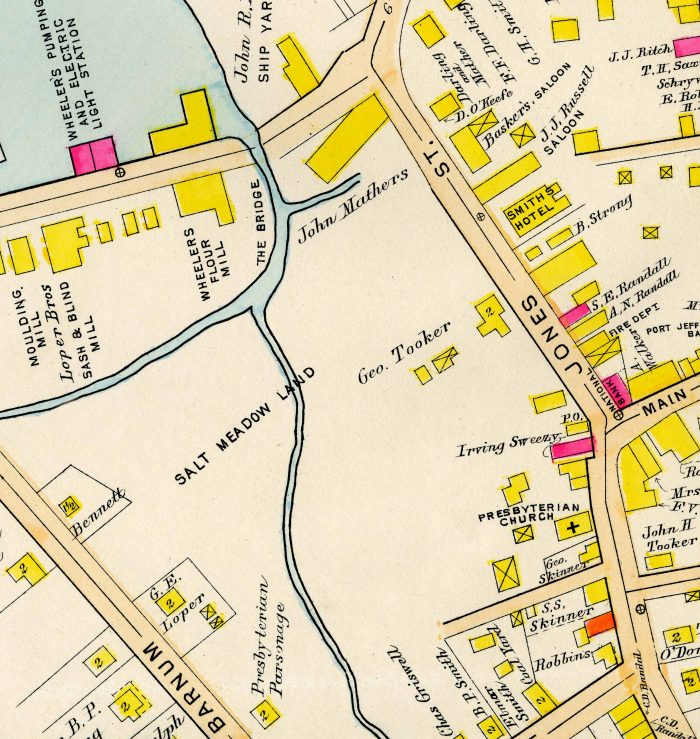

Respected Port Jefferson shipbuilder James M. Bayles was elected president of the Smithtown and Port Jefferson Rail Road Company, and Robert W. Wheeler, who ran a flour/saw mill in Port Jefferson, served on its board of directors. The corporation had an authorized capital stock of $200,000, divided into shares of $25 each.

After surveys were completed, rights-of-way secured and contracts finalized, construction began on the 18-mile road. Gangs worked from 1871-1873 on separate parts of the route. The eastern, or Port Jefferson section, employed 200 men under the direction of Captain John Scully.

On Monday, Jan. 13, 1873, the first train left Port Jefferson at 6 a.m. with 24 passengers for the over three-hour, 58-mile trip to Long Island City. The fare on the inaugural run was $1.90.

The terminal at Port Jefferson, including a depot, freight house, turntable, and platform, was located on the west side of today’s Main Street (Route 25A).

The coming of the Smithtown and Port Jefferson Rail Road Company, which was absorbed by the LIRR in 1892, raised property values in Port Jefferson and eased travel to and from the village.

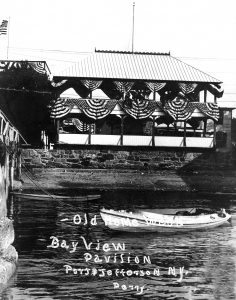

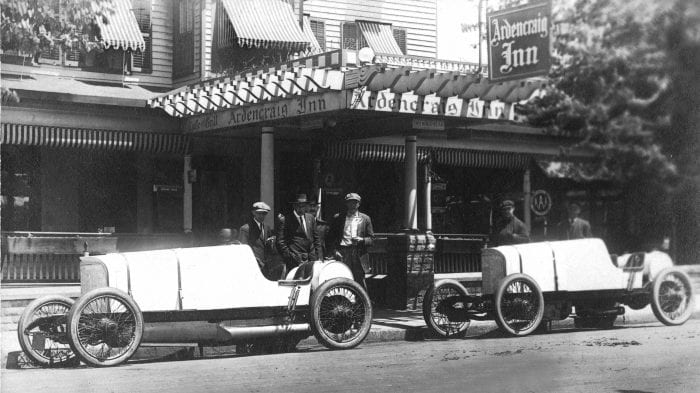

The railroad also brought tourists to Port Jefferson, hastened the village’s transition from a shipbuilding center to a vacationland, lessened Port Jefferson’s dependence on sea trade, and made the village a transit hub.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.