Study findings reveal a specific signal in one brain region that may hold the key

Researchers at Stony Brook University used genetic manipulation in a laboratory brain model to demonstrate that neurosteroids, signals involved in mood regulation and stress, can reduce the sensitivity and preference for sweet tastes when elevated within the gustatory cortex – a region in the brain most involved with taste. Their findings are published in Current Biology.

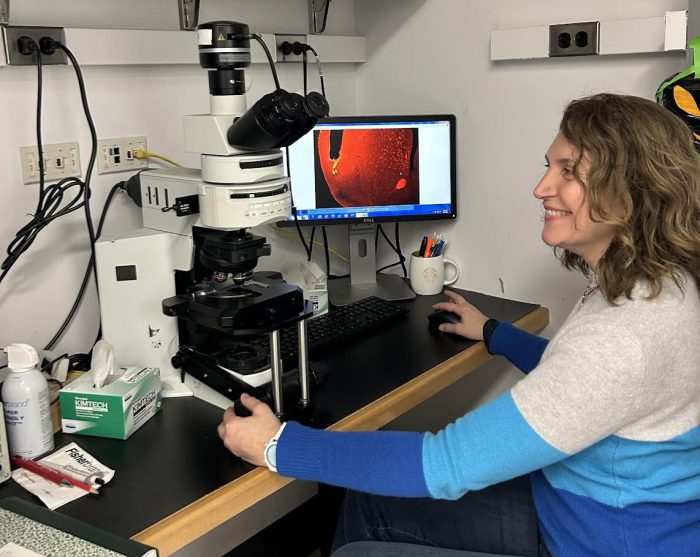

According to senior author Arianna Maffei, PhD, Professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, studies in humans suggest that the preference for certain foods influences how much we eat and that decreased sensitivity to taste is often associated with overconsumption, which may lead to obesity. Currently there is limited knowledge of how brain activity contributes to the differences in taste preference.

Determining the relationship between brain activity, taste and eating habits is difficult in humans because available technology for measuring changes in brain activity does not have sufficient resolution to identify biological mechanisms. However, scientists can accurately monitor brain activity in lab mice while measuring their taste preferences.

As the biology of taste is very similar in all mammals, this approach can shed light on the human brain and taste.

In their murine model, the research team investigated neural circuits regulating the preference for sweet taste in adult brains. Their work focused on the effect of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, which is known to be elevated in people affected by obesity.

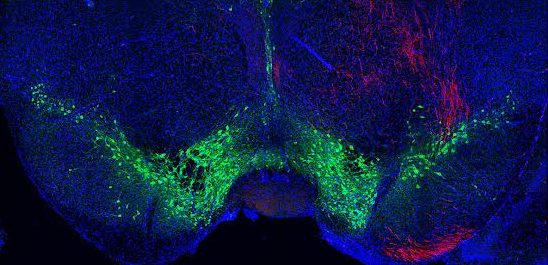

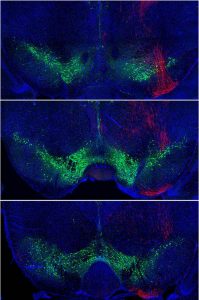

This neurosteroid modulates brain activity by increasing tonic inhibitory circuits mediated by a specific type of GABA receptor. The team demonstrated that these GABA receptors are present in excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the gustatory cortex.

They infused allopregnanolone locally into the gustatory cortex of the mice to activate neurosteroid-sensitive GABA receptors. This manipulation reduced the model’s sensitivity and preference for sweet taste. Then they used genetic tools to remove neurosteroid sensitive GABA receptors locally, only in the gustatory cortex. This manipulation eliminated the preference for sweet taste over water.

“This reduced sensitivity and preference for sweet taste was even more prominent if the receptors were selectively removed only from inhibitory gustatory cortex neurons. Indeed, in this case mice were practically unable to distinguish sugared water from water,” explains Maffei.

Their approach confirmed that a specific type of GABA receptor is the target of neurosteroid activity and is essential for fine-tuning sensitivity and preference for sweet taste.

Maffei says their findings illustrate the fascinating ways the mammalian brain contributes to the taste experience and reveals a specific signal in a specific brain region that is essential for sensitivity to sweet taste.

Ongoing research with the models is exploring whether neurosteroids only regulate sweet taste sensation or contribute to the perception of other tastes, and/or how changes in taste sensitivity influences eating.

The research was supported by several grants from the National Institute for Deafness and Communication Disorder (NIDCD) branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and was supported by NIH grants R01DC019827, R01DC013770, R01DC015234, F31 DC019518 and UF1NS115779.

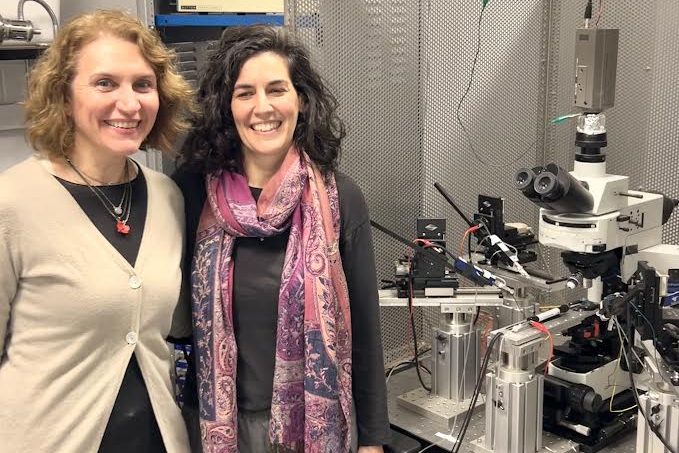

The authors are members of Stony Brook University’s College of Arts and Science (Yevoo and Maffei) and of the Renaissance School of Medicine (Fontanini).