Medical Compass: Weighing reflux disease treatment options

Increased fiber and exercise improve symptoms

By David Dunaief, M.D.

After a large meal, many people suffer from occasional heartburn and regurgitation, where stomach contents flow backward up the esophagus. This reflux happens when the lower esophageal sphincter, the valve between the stomach and esophagus, inappropriately relaxes. No one is quite sure why it happens with some people and not others. Many incidences of reflux are physiologic (normal functioning), especially after a meal, and doesn’t require medical treatment (1).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), on the other hand, is long-lasting and more serious, affecting as much as 28 percent of the U.S. population (2). This is one reason pharmaceutical firms give it so much attention, lining our drug store shelves with over-the-counter and prescription solutions.

GERD risk factors range from lifestyle — obesity, smoking and diet — to medications, like calcium channel blockers and antihistamines. Other medical conditions, like hiatal hernia and pregnancy, also contribute (3). Dietary triggers can also play a role. They can include spicy, salty, or fried foods, peppermint, and chocolate.

One study showed that both smoking and salt consumption added to the risk of GERD significantly (4). Risk increased 70 percent in people who smoked. Surprisingly, people who used table salt regularly saw the same increased risk as seen with smokers.

Let’s examine available treatments and ways to reduce your risk.

Evaluate medication options

The most common and effective medications for treating GERD are H2 receptor blockers (e.g., Zantac and Tagamet), which partially block acid production, and proton pump inhibitors (e.g., Nexium and Prevacid), which almost completely block acid production (5). Both classes of medicines have two levels: over-the-counter and prescription strength. Let’s focus on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), for which just over 90 million prescriptions are written every year in the U.S. (6).

The most frequently prescribed PPIs include Prilosec (omeprazole) and Protonix (pantoprazole). Studies show they are effective with short-term use in treating Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcers, GERD symptoms, and gastric ulcer prophylaxis associated with NSAID use (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) as well as upper gastrointestinal bleeds.

Most of the data in the package inserts is based on short-term studies lasting weeks, not years. The landmark study supporting long-term use approval was only one year. However, maintenance therapy usually continues over many years.

Side effects that have occurred after years of use include increased risk of bone fractures and calcium malabsorption; Clostridium difficile, a bacterial infection in the intestines; potential vitamin B12 deficiencies; and weight gain (7).

Understand PPI risks

The FDA warned that patients who use PPIs may be at increased risk of a bacterial infection called C. difficile. This is a serious infection that occurs in the intestines and requires treatment with antibiotics. Unfortunately, it only responds to a few antibiotics and that number is dwindling. In the FDA’s meta-analysis, 23 of 28 studies showed increased risk of infection. Patients need to contact their physicians if they develop diarrhea when taking PPIs and the diarrhea doesn’t improve (8).

Suppressing stomach acid over long periods can also result in malabsorption issues. In a study where PPIs were associated with B12 malabsorption, it usually took at least three years’ duration to cause this effect. While B12 was not absorbed properly from food, PPIs did not affect B12 levels from supplementation (9). If you are taking a PPI chronically, have your B12 and methylmalonic acid (a metabolite of B12) levels checked and discuss supplementation with your physician. Before stopping PPIs, consult your physician. Rebound hyperacidity (high acid produced) can result from stopping them abruptly.

Increase fiber and exercise

A number of modifications can improve GERD, such as raising the head of the bed about six inches, not eating prior to bedtime and obesity treatment, to name a few (10). In the study that quantified the risks of smoking and salt, fiber and exercise both had the opposite effect, reducing GERD risk (5). An analysis by Journal Watch suggests that the fiber effect may be due to its ability to reduce nitric oxide production, a relaxant for the lower esophageal sphincter (11).

Manage weight

In one study that examined obesity’s role in GERD exacerbation, researchers showed that obesity increases pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter significantly (12). Intragastric (within the stomach) pressures were higher in both overweight and obese patients on inspiration and on expiration, compared to those with normal body mass index.

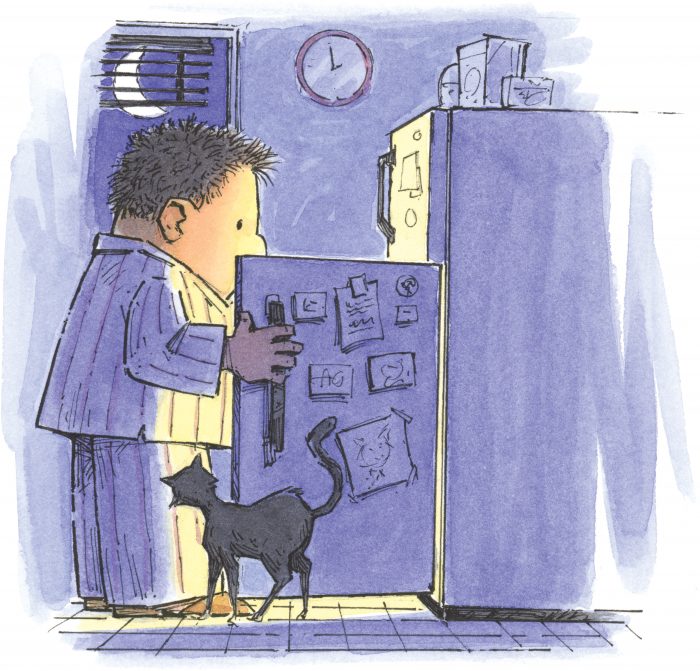

Avoid late night eating

One of the most powerful modifications we can make to avoid GERD is among the simplest. A study showed a 700 percent increased risk of GERD for those who ate within three hours of bedtime, compared to those who ate four hours or more prior to bedtime (13). Therefore, it is best to not eat right before bed and to avoid “midnight snacks.” While drugs have their place in the arsenal of options to treat GERD, lifestyle changes are the first, safest, and most effective approach in many instances.

References:

(1) Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25(1):75. (2) Gut. 2014 Jun; 63(6):871-80. (3) emedicinehealth.com. (4) Gut 2004 Dec; 53:1730-1735. (5) Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1392. (6) Kane SP. Proton Pump Inhibitor, ClinCalc DrugStats Database, Version 2022.08. Updated August 24, 2022. Accessed October 11, 2022. (7) World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(38):4794–4798. (8) www.FDA.gov. (9) Linus Pauling Institute; lpi.oregonstate.edu. (10) Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965-971. (11) JWatch Gastro. Feb. 16, 2005. (12) Gastroenterology 2006 Mar; 130:639-649. (13) Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Dec;100(12):2633-2636.

Dr. David Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management. For further information, visit www.medicalcompassmd.com.