By Daniel Dunaief

Over the course of decades, aging skin tends to wrinkle, revealing laugh or frown lines built up through a lifetime of laughter, tears and everything in between. Similarly, when people age, the proteins in their bodies don’t fold up as neatly. Free radicals cause these misfolded proteins, which are then susceptible to further damage.

The cumulative effect of these misfolded proteins, which is a part of natural cell aging, can contribute to cell death and, ultimately, the death of an individual.

Researchers have typically focused on the way one or two proteins unfold as damage increases from oxygen that has an uneven number of electrons.

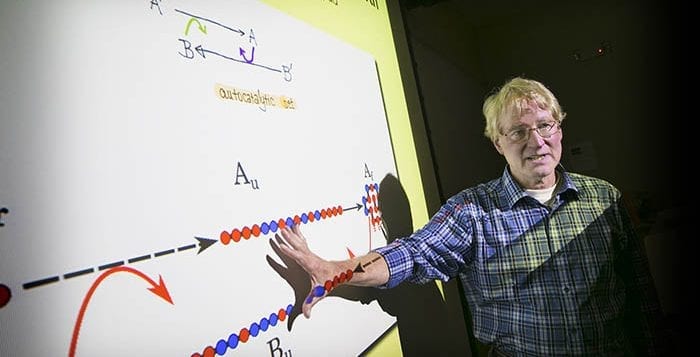

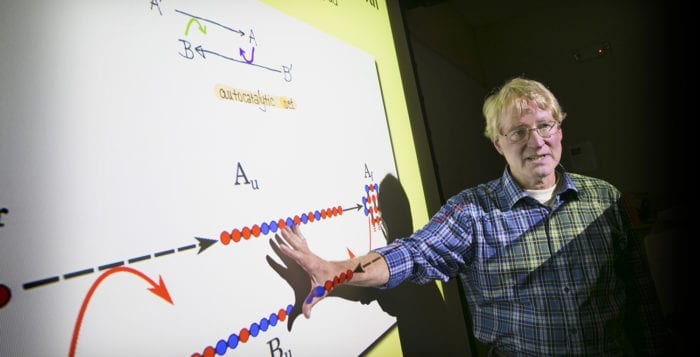

Ken Dill, a distinguished professor and director of the Laufer Center for Physical and Quantitative Biology at Stony Brook University, and colleagues including Adam de Graff, a former postdoctoral researcher in Dill’s lab who is currently a senior scientist at Methuselah Health based in Cambridge, England, and Mantu Santra, a postdoctoral researcher in Dill’s lab, recently published research that explored the global effects of unfolding on the proteome. Their model represents average proteins, not individual proteins, detail by detail.

Researchers use the roundworm as a model of human aging because of the similarity of the main processes. The worm model presents opportunities to explore the cumulative effect on proteins because of its shorter life span. Worms in normal conditions typically live about 20 days. Worms, however, that are subjected to higher temperatures or that live in the presence of free radicals can survive for only a few hours.

The shorter life span correlates with the imbalance between the rate at which cells create new proteins and the collapse of misfolded proteins damaged by free radicals, the scientists explained in a paper published online recently in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While numerous processes occur during aging, including changes in DNA, lipids and energy processes, Dill explained that organisms, from worms, to flies, to mice to humans experience increasing oxidative damage over the course of their lives.

“The evidence made us think about proteome collapse as a dominant process,” Dill said.

De Graff explained that the paper uses the premise that “certain conformations of a protein are much more susceptible to oxidative damage than others. If you’re folded, you’re pretty safe.”

In the past, researchers have considered linking the way protein misfolding leads to cell death to a potential approach to cancer. If, for example, scientists could subject specific cancer cells to oxidative damage and to develop an accumulation of misfolded proteins, they could selectively kill those cells.

A few years ago, researchers explored the possibility of developing a therapeutic strategy that tapped into the mechanism of cell death. To survive with an accumulation of mutated proteins, cancer cells have increased the levels of chaperone concentrations because they need to handle numerous mutated, incorrectly folded proteins.

A drug called 17-AAG aimed to reduce the chaperones. It worked for some cancers but not others and had side effects. New efforts are continuing in this area, Dill said.

Other researchers, including De Graff, are looking at ways to improve protein folding and, potentially, provide therapeutic benefits for people as they age.

At Methuselah Health De Graff and his colleagues are leveraging the fact that certain conformations are more susceptible to damage and thus the creation of altered “proteoforms.” Identifying these proteoforms could be key to the early detection of disease and the development of preventative treatments, De Graff explained.

Methuselah Health is not interested in treating the downstream symptoms of disease but, rather, its upstream causes.

Going forward, Dill hopes other experimental scientists continue to generate data that enables a closer look at the link between oxidative damage, protein misfolding and cell death.

Some people in the aging field look at individual proteins, he explained. In neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, which are associated and correlated with protein misfolding, scientists are taking numerous approaches. So far, however, researchers haven’t found a successful approach to tackle aging or diseases by altering misfolded proteins.

Dill hopes people will come to appreciate a role for modeling in understanding such varied cellwide processes such as aging. “How do we convey to people who are used to thinking about detailed biochemistry why modeling matters at all?” he asked. “We have our work cut out for us to communicate what we think matters and a way forward in terms of drug discovery.”

Theoretically, some proteins that are at a high enough concentration might be more important in the aging and cell death process than others, Dill said. “If you could reduce their concentration, you might pull the cell back from the tipping point for other proteins,” he said, but researchers know too little about if or how they should do this. He credits De Graff and Santra with doing considerable work to bring this study together.

A resident of Port Jefferson with his wife, Jolanda Schreurs, Dill is pleased that their house has solar panels.

The couple’s son Tyler is married and has purchased a house in San Diego. Despite professing a lack of interest in biology at an early age, Tyler is working as a staff development engineer for Illumina, a company that makes DNA sequencing machines.

The couple’s younger son Ryan is earning his doctorate as a physical chemist at the University of Colorado in Boulder. He works with lasers, solar energy and quantum entanglements.

As for the most recent research, Dill suggested that it is “premised on the importance of oxidative damage, including by free radicals, which is now well established,” he explained in an email. “It then seeks to explain their effects on how proteins fold and misfold.”

De Graff added that the model in the PNAS paper attempts to “understand the consequences of slowed protein synthesis and turnover” that occurs during aging.