Remedy Plan proposes a non-toxic approach to cancer treatment

Say what you will about Gen-Xers, but the founders of Remedy Plan could just change the world.

Greg Crimmins, CEO and co-founder of Remedy Plan, is a molecular and cell biologist, working on a way to stop the spread of cancer.

Yes, you read that correctly. A way to stop cancer. That’s huge.

Though they’re not there yet, the plan is very much in place — “Stop the spread of cancer without stopping your life.”

With Vice President Joe Biden chairing the first meeting of the Cancer Moonshot Task Force in February, we are all reminded of the toll the deadly disease takes on its victims, their families and their friends. And any new perspectives are welcome in the battle to end the disease’s tyranny.

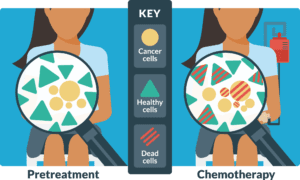

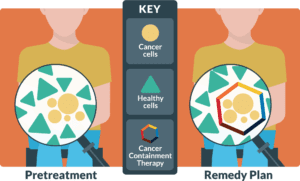

Departing from the traditional approach to cancer treatment, Remedy Plan won’t kill cancer cells. Crimmins said it will contain them so that they can’t spread.

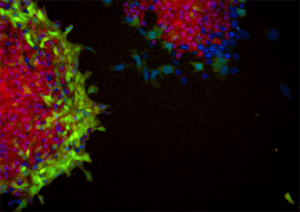

Cancer cells, he explained, are actually cells that have regressed to an embryonic state and hold properties that are only present in the very early stages of human development.

“We’re not attaching molecular atomic bombs to try to kill any cells at all,” he said.

“We are targeting embryonic properties of cells which are not present in any healthy cells.”

Based on co-founder Ron Parchem’s research in embryonic stem cell biology and Crimmins’ background creating phenotypic screens, the former University of California, Berkeley classmates were able to develop a tool to easily identify the most dangerous cancer cells and to “measure quickly and effectively which drugs can remove the metastatic properties of cancer cells,” Crimmins said.

He talked about what it was like when he and his friend realized that they were on to something big.

“It was that moment where this sort of light gets flicked on, and everything that was dark all of a sudden, you can see it for a moment….” Crimmins said.

“The potential was so big, and the science was solid.”

So big and so solid, in fact, that Crimmins, 35, turned down a tenure-track position at the University of Maryland to pursue Remedy Plan and to begin screening drugs to determine the initial group of potential candidates.

While his wife Allison, an environmental scientist, started a new job at the Environmental Protection Agency in D.C., Crimmins spent about three months — and his savings — sleeping on a friend’s couch in San Francisco getting the project off the ground.

Crimmins and Parchem, a professor at Baylor College of Medicine, assembled an advisory team of scientists from Tufts School of Medicine, University of California, Berkeley and University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Cancer Center.

To raise seed money for the project, the founders developed a business plan before going to investors, applying for grants and even launching an Indiegogo campaign.

While most people don’t exactly associate crowdfunding with a for-profit biotech start-up, the $102,925 the campaign raised was crucial to Crimmins being able to test 1,000 FDA-approved drugs.

“Part of doing a crowdfunding campaign is you’re pulling all of these people in. You’re letting them be a part of science,” said Allison Crimmins, who also functions as director of strategy for Remedy Plan.

“You have a responsibility too — you’ve got to maintain these updates or blog or something that lets them be a part of your successes and failures along the way,” she said.

Their more than 280 contributors helped them surpass their $100,000 goal and made it possible for Crimmins to leave his “day” job — he was a research fellow at the Food and Drug Administration — to open his lab in Rockville, MD earlier this winter.

Ultimately, they will need about $1.5 million and are continuing to approach angel investors. The funds will go toward hiring additional staff and testing drugs for safety and their ability to stop metastatic cancer in animal models. It will also go toward optimizing the chemistry of the drug candidates that are most likely to make the cut for clinical trials.

Though this could take a few years, Crimmins is in it for the long haul.

“This is something that could change the system of cancer treatment if we’re successful,” he said.