Chest pain is only one indicator

By David Dunaief, M.D.

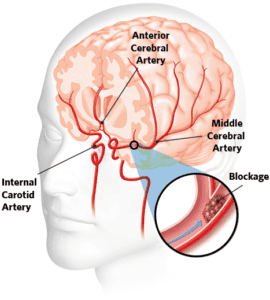

Heart disease is the most common chronic disease in America. When we refer to heart disease, it is an umbrella term; heart attacks are one component. Fortunately, the incidence of heart attacks has decreased over the last several decades, as have deaths from heart attacks. However, there are still 720,000 heart attacks every year, and more than two-thirds are first heart attacks (1).

How can we further improve these statistics and save more lives? We can do this by increasing awareness and education about heart attacks. It is a multifaceted approach: recognizing the symptoms and knowing what to do if you think you’re having a heart attack.

If you think someone is having a heart attack, call 911 as quickly as possible and have the patient chew an adult aspirin (325 mg) or four baby aspirins. Note that the Food and Drug Administration does not recommend aspirin for primary prevention of a heart attack. However, the use of aspirin here is for treatment of a potential heart attack, not prevention. It is also very important to know the risk factors and how to potentially modify them.

Heart attack symptoms

The main symptom is chest pain, which most people don’t have trouble recognizing. However, there are a number of other, more subtle, symptoms such as discomfort or pain in the jaw, neck, back, arms and epigastric, or upper abdominal, areas. Others include nausea, shortness of breath, sweating, light-headedness and tachycardia (racing heart rate). One problem is that less than one-third of people know these other major symptoms (2). About 10 percent of patients present with atypical symptoms — without chest pain — according to one study (3).

It is not only difficult for the patient but also for the medical community, especially the emergency room, to determine who is having a heart attack. Fortunately, approximately 80 to 85 percent of chest pain sufferers are not having a heart attack. More likely, they have indigestion, reflux or other non-life-threatening ailments.

There has been a raging debate about whether men and women have different symptoms when it comes to heart attacks. Several studies speak to this topic. Let’s look at the evidence.

Men vs. women

There is data showing that, although men have heart attacks more commonly, women are more likely to die from a heart attack (4). In a Swedish prospective (forward-looking) study, after having a heart attack, a significantly greater number of women died in hospital or near-term when compared to men. The women received reperfusion therapy, artery opening treatment that consisted of medications or invasive procedures less often than the men.

However, recurrent heart attacks occurred at the same rate, regardless of sex. Both men and women had similar findings on an electrocardiogram; they both had what we call ST elevations. This was a study involving approximately 54,000 heart attack patients, with one-third of them being women.

One theory about why women are treated less aggressively when first presenting in the ER is that they have different and more subtle symptoms — even chest pain symptoms may be different. Women’s symptoms may include pain in the lower portion of the chest or upper portion of the abdomen and may have significantly less severe pain that could radiate or spread to the arms. But, is this true? Not according to several studies.

In one observational study, results showed that, though there were some subtle differences in chest pain, on the whole, when men and women presented with this main symptom, it was of a similar nature (5). There were 34 chest pain characteristic questions used to determine if a difference existed. These included location, quality or type of pain and duration. Of these, there was some small amount of divergence: The duration was shorter for a man (2 to 30 minutes), and pain subsided more for men than for women. The study included approximately 2,500 patients, all of whom had chest pain. The authors concluded that determination of heart attacks with chest pain symptoms should not factor in the sex of patients.

This trial involved an older population; patients were a median age of 70 for women and 59 for men, with more men having had a prior heart attack. This was a conspicuous weakness of an otherwise mostly solid study, since age and previous heart attack history are important factors.

Therefore, I thought it apt to present another observational study with a younger population, where there was no significant difference in age; the median age of both men and women was 49. In this GENESIS-PRAXY study, results showed that chest pain remained the most prevalent presenting symptom in both men and women (6). However, of the patients who presented without distinct chest pain and with less specific EKG findings (non-ST elevations), significantly more were women than men. Those who did not have chest pain symptoms may have had some of the following symptoms: back discomfort, weakness, discomfort or pain in the throat, neck, right arm and/or shoulder, flushing, nausea, vomiting and headache.

If the patients did not have chest pain, regardless of sex, the symptoms were, unfortunately, diffuse and nonspecific. The researchers were looking at acute coronary syndrome, which encompasses heart attacks. In this case, independent risk factors for disease not related to chest pain included both tachycardia (rapid heart rate) and being female. The authors concluded that there need to be better ways to calibrate non-chest pain symptoms.Some studies imply that as much as 35 percent of patients do not present with chest pain as their primary complaint (7).

Let’s summarize

So what have we learned about heart attack symptoms? The simplest lessons are that most patients have chest pain, and that both men and women have similar types of chest pain. However, this is where the simplicity stops and the complexity begins. The percentage of patients who present without chest pain seems to vary significantly depending on the study — ranging from less than 10 percent to 35 percent.

Therefore, it is even difficult to quantify the number of non-chest pain heart attacks. This is why it is even more important to be aware of the symptoms. Non-chest pain heart attacks have a bevy of diffuse symptoms, including obscure pain, nausea, shortness of breath and light-headedness. This is seen in both men and women, although it occurs more often in women. When it comes to heart attacks, suspicion should be based on the same symptoms for both sexes. Therefore, know the symptoms, for it may be your life or a loved one’s that depends on it.

References:

(1) Circulation. 2014;128. (2) MMWR. 2008;57:175–179. (3) Chest. 2004;126:461-469. (4) Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1041-1047. (5) JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Feb. 1;174:241-249. (6) JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1863-1871. (7) JAMA. 2012;307:813-822.

Dr. Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management.