By Daniel Dunaief

The cardiovascular skies may be clear and sunny, but there could also be a storm lurking behind them. About one in eight people who get a normal reading for their blood pressure have what’s called masked hypertension.

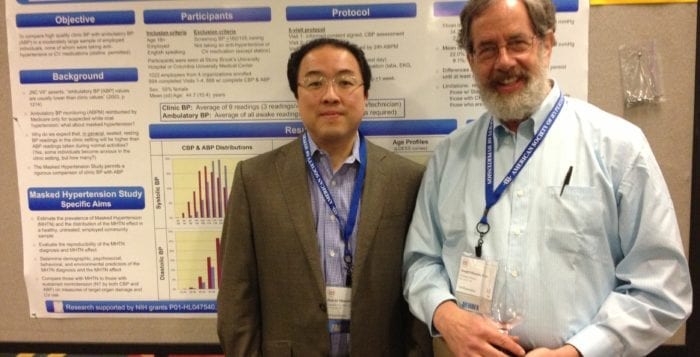

That’s the finding in a recent study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology led by Joseph Schwartz, a professor of psychiatry and sociology at Stony Brook University and a lecturer of medicine at the Columbia University Medical Center. Schwartz said his research suggests that some people may need closer monitoring to pick up the kinds of warning signs that might lead to serious conditions.

“The literature clearly shows that those with masked hypertension are more likely to have subclinical disease and are at an increased risk of a future heart attack or stroke,” Schwartz explained in an email.

Schwartz and his colleagues measured ambulatory blood pressure, in which test subjects wore a device that records blood pressure about every half hour, collecting a set of readings as a person goes about the ordinary tasks involved in his or her life. Through this reading, he was able, with some statistical monitoring, to determine that about 17 million Americans have masked hypertension, a term he coined in 2002.

Schwartz, who started studying ambulatory blood pressure in the late 1980s, has been actively exploring masked hypertension for over a decade. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is more effective at predicting subclinical disease such as left ventricular hypertrophy and the risk of future cardiovascular events, said Schwartz. “There was some rapidly growing evidence it was a better predictor of who would have a heart attack or stroke than in the clinic, even when the blood pressure in the clinic was properly measured,” he said.

To be sure, the expense of 24-hour monitoring of ambulatory blood pressure for everyone is unwieldy and unrealistic, Schwartz said. The list price for having an ambulatory blood pressure recording is $200 to $400, he said. Wearing the device is also a nuisance, which most people wouldn’t accept unless it was likely to be clinically useful or, as he suggested, they were paid as a research participant.

Schwartz said he used a model similar to one an economist might employ. Economists, he said, develop simulation models all the time. He said over 900 people visited the clinic three times as a part of the study. The researchers took three blood pressure readings at each visit. The average of those readings was more reliable than a single reading.

The study participants then provided 30 to 40 blood pressure readings in a day and averaged those numbers. He collected separate data for periods when people were awake or asleep. A patient close to the line for hypertension in the clinical setting was the most likely to cross the boundaries that define hypertension. “You don’t have that far to go to cross that boundary,” Schwartz said.

After analyzing the information, he came up with a rate of about 12.3 percent for masked hypertension of those with a normal clinic blood pressure. The rate was even higher, at 15.7 percent, when the researchers used an average of the nine readings taken during the patient’s first three study visits.

William White, a professor of medicine at the Calhoun Cardiology Center at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington was a reviewer for one of these major studies. “They are excellent,” said White, who has known Schwartz for about a decade. “We should be monitoring blood pressure more outside of the clinical environment.”

Indeed, patients have become increasingly interested in checking their blood pressure outside of the doctor’s offices. “We have a 200 to 300 percent increase in requests for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring from our clinical lab during the last five to ten years — in all age groups, genders and ethnicities,” explained White.

The challenge, however, is that tracking hypertension closely for every possible patient is difficult clinically and financially. “There are no obvious clinical markers for masked hypertension other than unexpectedly high self-blood pressure or unexplained hypertensive target organ damage,” White added.

Schwartz himself has a family history that includes cardiovascular challenges. His father, Richard Schwartz, who conducted nonmedical research, has a long history of cardiovascular disease and had a heart attack at the age of 53. His grandfather had a fatal heart attack at the same age. When Schwartz reached 53, he said he had “second thoughts,” and wanted to get through that year without having a heart attack. He’s monitoring his own health carefully and is the first one in his family to take blood pressure medication.

Schwartz, who grew up in Ithaca, New York, came to Stony Brook University in 1987. He called his upbringing a “nonstressful place to grow up.” He now lives in East Setauket with his wife Madeline Taylor, who is a retired school teacher from the Middle Country school district. The couple has two children. Lia lives in Westchester and works at Graham Windham School and Jeremy lives in Chelsea and works for Credit Suisse.

As for his work, Schwartz said the current study on masked hypertension was a part of a broader effort to categorize and understand pre-clinical indications of heart problems and to track the development of hypertension.

Now that he has an estimate of how many people might have masked hypertension, he plans to explore the data further. That analysis will examine whether having masked hypertension puts a patient at risk of having cardiovascular disease or other circulatory challenges. “We are very interested in whether certain personality characteristics and/or circumstances (stressful work situation) makes it more likely that one will have masked hypertension,” he explained.