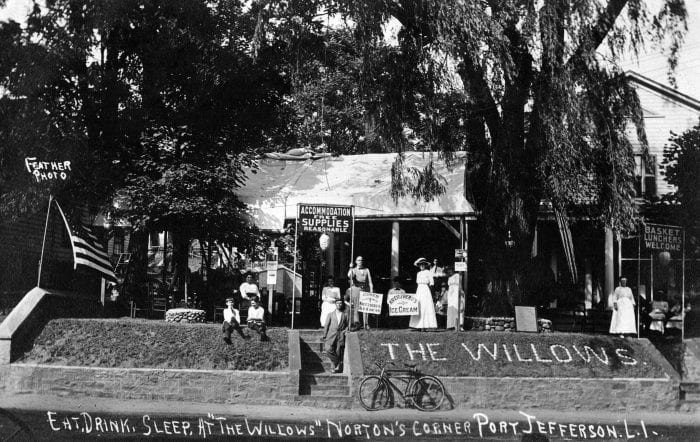

Smith’s Hotel was established in 1870 and located in Port Jefferson on the east side of Main Street, a short distance from the waterfront.

William R. Thompson began leasing the venerable hotel in 1908 from its longtime proprietor Lizzie Smith before actually buying the establishment in 1910.

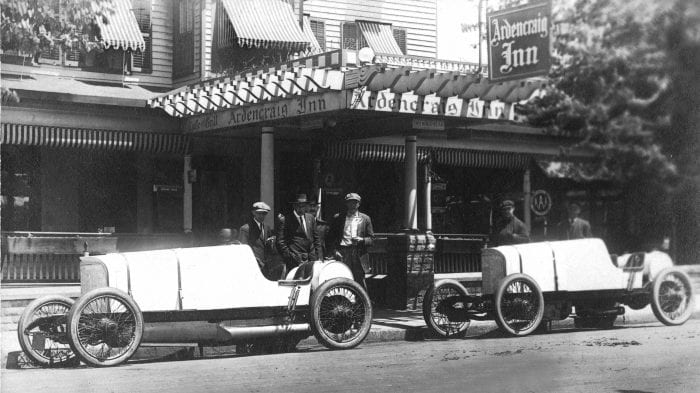

Besides renaming the hotel the Ardencraig Inn, Thompson made other changes at the premises, adding guest rooms, enlarging the dining room, installing Blau-Gas lighting and introducing sanitary plumbing.

More important, Thompson recognized how automobiles were revolutionizing travel, giving people the freedom to explore the open road, and creating a new class of tourists no longer dependent on ships and trains.

To tap into this burgeoning market and popularize the Ardencraig, Thompson geared his publicity toward motorists.

The inn was featured in travel guides favored by car aficionados such as The American Motorist and The Automobile Blue Book.

With the ferry Park City running between Bridgeport and Port Jefferson, the Ardencraig was described in the Connecticut press as being ideally located to host “automobile parties” from New England.

A car enthusiast himself, Thompson was a member of the Automobile Club of Port Jefferson, which sponsored both the 1910 and 1911 Hill Climbs on the village’s East Broadway.

As a service for the motorists who were registered at the Ardencraig, Thompson had a garage constructed behind the inn. Besides providing accommodations for chauffeurs, the garage was manned day and night.

While welcoming motorists to his hotel, Thompson did not neglect tourists who had arrived in Port Jefferson by rail or yacht. Events such as Old Home Week in 1911 brought thousands to the village, numbers of whom stayed at the Ardencraig.

Advertised in Port Jefferson’s newspapers as a “popular place for particular people,” the inn was also known among villagers for family gatherings, wedding receptions, card parties and balls.

After years of success, the Ardencraig’s run of good luck ended on March 2, 1920, when the inn was destroyed by a fire that purportedly originated with a defective flue. The hotel’s staff and guests, as well as Thompson and his wife, all escaped the burning building.

Following the blaze, Thompson presented plans to replace the Ardencraig with a 75-room hotel and an adjoining 1,300-seat theater, but without a sufficient number of investors, the project died.

Undaunted, Thompson built a new business on the site of his former hotel. Opening in 1920, the Ardencraig Bowling Alleys and Billiard Parlor was located on the north side of Arden Place. Known as the “Annex,” the structure featured three Brunswick alleys and four billiard tables on the first floor and a rooming house on the second.

The Ardencraig Alleys flouted the prohibition laws, leading to Thompson’s arrest in both 1922 and 1923 for illegally selling alcoholic beverages. After more violations of the Volstead Act, a judge granted a padlock injunction closing the business for one year.

The Ardencraig Alleys reopened in 1924, but without Thompson as the proprietor. He had leased the establishment to managers who had pledged to respect the dry laws.

Thompson left Port Jefferson in 1926 and became the treasurer of the Long Island Association. His move triggered more talks about building a hotel on the Ardencraig site, but again nothing materialized.

Meanwhile, the renamed Ardencraig Bowling and Billiard Academy operated under a succession of managers but closed because of lagging business. There was a call to purchase the property and use the building as a community center, but the proposal fell on deaf ears.

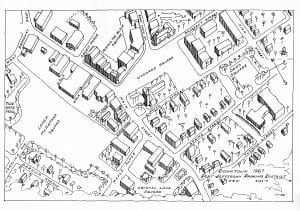

Although there was little interest in developing a hotel or community center on the Ardencraig site, the land was valued for other purposes.

The Port Jefferson Fire Department often used the empty Ardencraig property to hold its annual summer carnivals.

Because of its prized location in downtown Port Jefferson, the vacant Ardencraig space was also seen as an ideal location for a public parking lot.

In 1937, the Port Jefferson Merchants Association leased the Ardencraig site from its owner, Mary Thompson, the widow of William R. Thompson.

A portion of the Ardencraig property was quickly transformed into a parking lot, which opened in 1937 to applause from shoppers and shopkeepers alike.

Following Mary Thompson’s death in 1942, the Ardencraig property was sold at auction with the winning bid going to Port Jefferson’s First National Bank.

Under the Bank’s direction, the dilapidated “Annex” was demolished. The east end of the Ardencraig property was then graded and opened for free parking in 1943.

In 1948, Robert F. Wells purchased the Ardencraig property, where he built an Oldsmobile showroom and service center. Opening in 1949, the dealership itself was located on the corner of Main Street and Arden Place. A parking area for customers and a used car lot was to its rear.

With the closing of the Oldsmobile agency, the space was home to a Gristede’s supermarket and later The GAP. As of this writing, the building is unoccupied. The balance of the former Ardencraig property is now the site of a Port Jefferson Village parking lot.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.