Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Antebellum, the new psychological horror film, opens with a William Faulkner epigraph: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

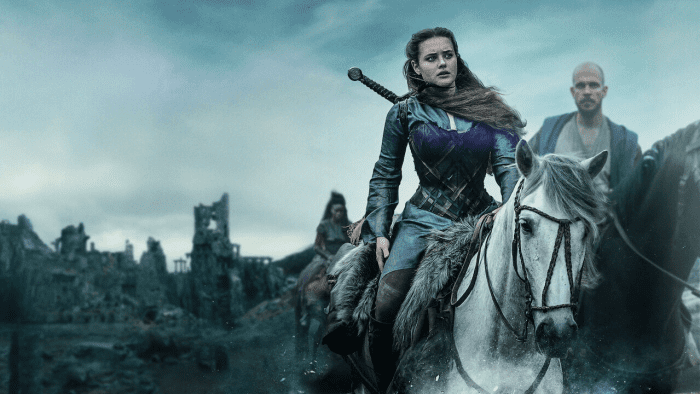

This immediately segues into a bucolic image of a plantation in the Confederate south. The sky is a vivid blue and the grass a verdant green. It is a rich and welcoming landscape, contrasting with an ominous soundtrack of soaring strings. And, like a twisted version of Colonial Williamsburg, this bright backdrop enhances the ugly and chilling murder of a runaway slave.

The horror of life on this plantation is seen through the eyes of a slave named Eden. Commandeered by the Confederate army, the slaves are not allowed to speak, are constantly tortured, and the women are sexually abused. It is a savage and sadistic portrayal. There is a feeling that this is presented as a distortion to the soft-sell of Gone with the Wind.

About forty minutes in, a ringing cell phone shifts the entire narrative. Eden wakes up, and it is revealed at that she is actually Dr. Veronica Henley, a sociologist and activist, living with her loving husband and daughter in a well-appointed, if sterile, townhouse in present time. Henley flies to New Orleans to promote her new book, Shedding the Coping Persona. Following a dinner with friends, she is abducted and is next seen [spoiler alert] back on the plantation, where she once again is shown fighting for her life.

Antebellum is a twisty thriller in the vein of M. Night Shyamalan, where things are not what they seem. The remainder of the film is watching Veronica/Eden struggle from captive to victor. It is unflinching in its violence and viciousness which is certainly not inappropriate but sometimes feels voyeuristic.

Writer-directors Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz had a great concept and have directed the film with high style, leaning into this not-quite-real world. Initially, the slow unwinding of the mystery is highly effective. They present an intriguing premise and drive it with relentless tension. For a good part of the film, there is anticipation with the promise of revelation: a horrifying puzzle that will disclose its solution in due course.

However, the dialogue is stilted and the character development wanting. We never know who these people are; both victims and perpetrators are reduced to types rather than fully realized human beings. Given that Antebellum is offered as part of the horror genre, this would almost be acceptable. However, the film strives to be more. It is trying to make a statement about then and now — about the “unresolved past wreaking havoc on the present.” In this area, it doesn’t quite land. There are nods to the continuing social divide and the subtler forms of racism — a rude concierge, a bad table at a restaurant — but we’re never sure if this is part of the nightmare scenario or the social commentary. Maybe they are suggesting it is both but the lack of clarity muddles the point. There is also a great deal of heavy-handed symbolism that feels very film-school-clever.

Perhaps its biggest flaw is the unsatisfying conclusion. The ending fails to explain what has really happened. The absence of the who and the how make for an ambivalent collapse of the story and serves neither the social argument nor the narrative.

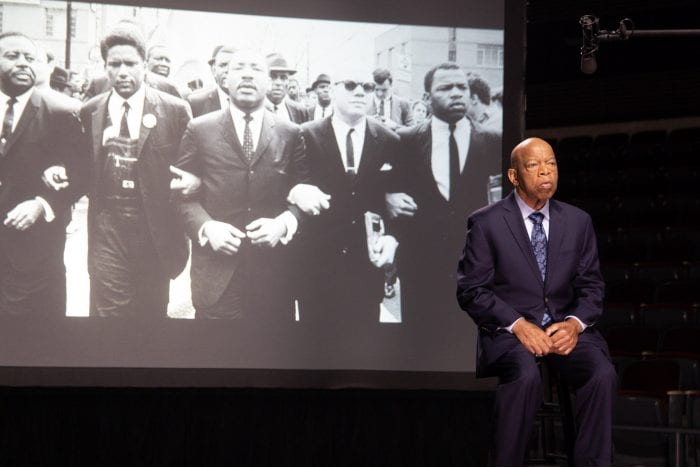

The radiant Janelle Monáe (Moonlight, Hidden Figures, Harriet) anchors the film as Veronica/Eden. Her extraordinary ability makes both worlds believable and present. She navigates the pitfalls, and there is never a wasted gesture. Her performance is a tribute to the economy of good acting, and she makes some of the more dramatic excesses real.

Gabourey Sidibe (best known for her exceptional, award-winning performance in Precious), as Veronica’s gal-pal Dawn, has a vivacity that would seem more at home in a rom-com. However, she infuses her screen time with a much needed energy. Jena Malone (Contact, The Hunger Games series) plays the over-the-top antagonist with great style, but it all feels rather James Bond villain.

Robert Aramayo, as Veronica’s husband, Daniel, is a warm and likable helpmate but he is barely in the movie. As for the rest of the cast, it is composed of slaves and soldiers who are not developed beyond standard tropes. An example is Tongayi Chirisa who makes the most of his few moments, but his story is left in the periphery, and we are never allowed to see who he really is.

Pedro Luque’s cinematography shifts from the lush plantation to the harsh, stark whites of the townhouse, to the murky city night, and back to the plantation. His strong, if on-the-nose, visuals successfully enhance the overall disconnect.

It is inevitable that comparisons with Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Us are going to be made. With those films, the creators skillfully blended horror with social awareness. They told their stories well and that clarity helped to further the commentary without sacrificing the artistry. Ultimately, Antebellum had the potential to transcend genre — but potential unfulfilled.

Rated R, Antebellum is now on demand.