By Victoria Espinoza

Fishing is a nearly $2 billion industry on Long Island, bringing hundreds of jobs to Suffolk County annually. Rising water temperature has the potential to drastically change the business.

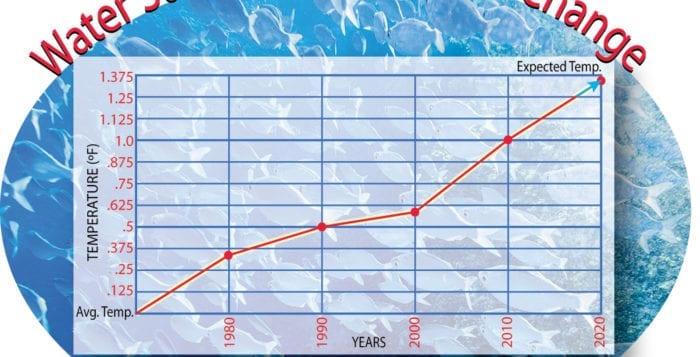

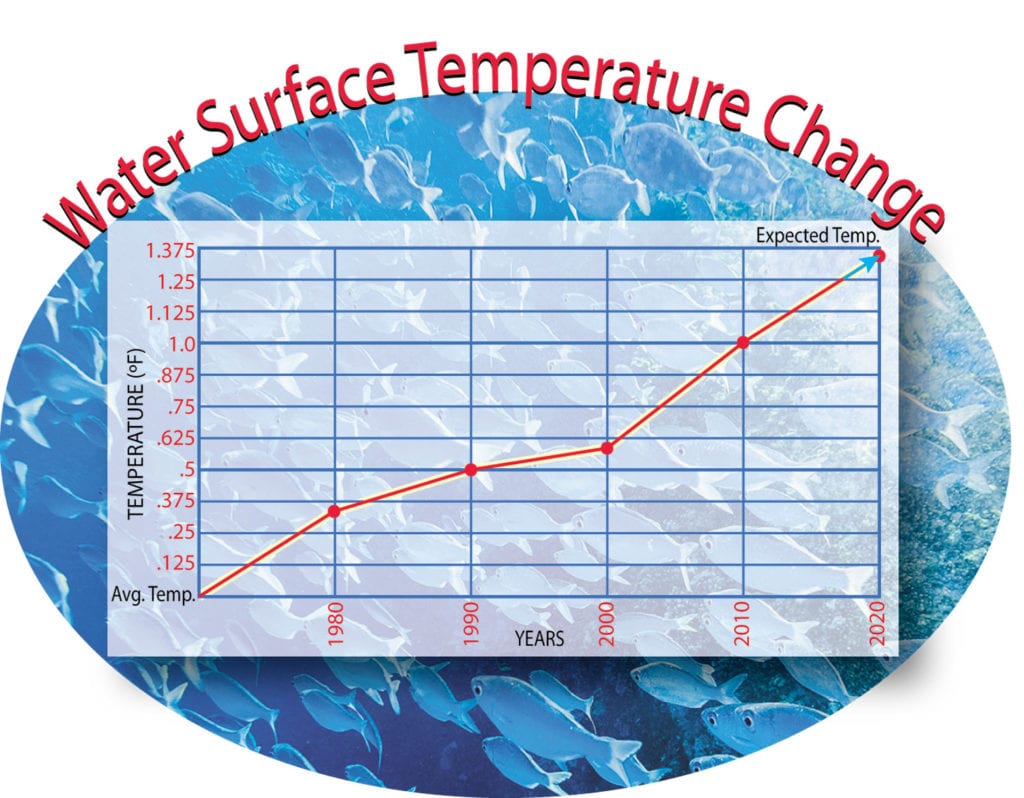

Water temperatures have been consistently increasing, and scientists and professionals said this trend could disrupt and permanently alter the species of fish that reside in local waters.

Lobster

More than twenty years ago, Northport and other coastal towns and villages on Long Island enjoyed a prosperous lobster fishing market. Flash forward to 2017, and that market is a distant memory. In the late 1990s, the lobster population effectively “died out” in the Long Island Sound. Kim McKown, unit leader for marine invertebrates and protected resources for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation said at the time scientists declared it “a commercial fishing disaster.”

“Researchers felt that it was the perfect storm,” McKown said in a phone interview. She said studies done concluded increased water temperatures led to added stress for lobsters, which affected their immune system and caused their demise. It was discovered lobsters in the Sound had suffered from hypoxia, a lack of oxygen in the water. Hypoxia is caused by warmer water, as warm water is able to hold less oxygen than cold — and this condition can also cause an increase in nitrogen levels, another harmful effect on fish. Hypoxia has occurred in the summer months in the Sound for decades, varying in longevity and density.

According to the Long Island Sound Study, “Sound Health 2012,” conducted by the NYSDEC, the area where hypoxia occurred in that summer “was the fifth largest since 1987 — 289 square miles, about 13 times the size of Manhattan.” It also lasted “80 days, 23 more than average between the years 1987 and 2012.” As water temperature levels rise, so does the duration of hypoxia in the water.

“Water temperatures were so high [then], scientists also found a new disease in lobster.”

—Kim McKown

“Water temperatures were so high [then], scientists also found a new disease in lobster,” McKown said. The disease was calcinosis, which results in calcium deposits forming crystals in the lobsters’ antenna glands. It was discovered in the remains of dead lobsters.

According to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, the organization tracking lobster population in southern New England, including the Long Island Sound, the population has continued to dwindle since the late ’90s. A record low population count occurred in 2013 and the organization said the stock is “severely depleted.”

“These declines are largely in response to adverse environmental conditions including increasing water temperatures over the last 15 years,” the ASMFC said in a study.

Huntington fishing captain James Schneider substantiated the data based on his own observations, saying the lobster population has not bounced back in full since then, although he has started to see more in recent years.

Winter flounder

Lobsters are not the only species in the Sound impacted by increased water temperatures. “Ask any fisherman the last time they caught a winter flounder,” Mark Tedesco, the director of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Long Island Sound Office, said in a phone interview. “They’ll probably tell you, boy, there aren’t too many of them out there.”

Tedesco’s claim was backed up by another captain. “Winter flounder have been diminished big time,” Northport fishing captain Stuart Paterson said in a phone interview.

He remembers fishing for winter flounder all the time as a kid in the spring and the fall. That’s no longer the case. “It’s really been a shame,” he said.

The ASMFC’s tracking of winter flounder proves the fish has had a species dip mirroring the southern New England lobster. In 1984 winter flounder landing, or total catch, was at almost 35 million pounds. In 2010 the winter flounder hit their lowest landing total — just 3.5 million pounds.

“The flounders are on the same levels as the lobsters, it’s a slow and grueling comeback,” Schneider said. He also said he saw winter flounder suffering from a familiar foe — hypoxia and increased levels of nitrate.

The reason for the disappearing fish is indicated in its name — a winter flounder has a hard time thriving in a Long Island Sound with warming temperatures. The ASMFC cites habitat degradation as one of the reasons the population has decreased, along with overfishing and low genetic variability.

That’s not to say all flounder species are vanishing from the water. Fishermen agree flukes, also known as summer flounder, are seeing steady growth.

“There is a lot more fluke flounder than there used to be,” Paterson said. “Their stock is vibrant.”

The trend is not surprising to the Long Island Sound Study. “Many cold water species common in Long Island Sound have been declining in abundance over the last two decades, while many warm water fishes have been increasing,” its “Sound Health 2012” report stated.

“Historic sea surface temperature data…show[s] a significant warming trend along the U.S. coast… that exceeds local atmospheric temperature increases and is comparable to the warming rates of the Arctic.”

—University of Connecticut study

Lori Severino, public information officer for the NYSDEC said in an email as black sea bass numbers have increased, fish like winter flounder have dwindled.

“A number of colder water species have declined, including American lobster and the winter flounder,” she said.

Long Island Sound Study leader Tedesco said he wouldn’t rule out the possible impact of water temperatures in the shifts in population of fish species in the Sound.

“Fishermen are used to seeing changes in populations, and sometimes that’s because of fishing pressure but it can also be because of these larger changes in climate,” Tedesco said.

The future of species in the Sound is far from clear if climate change continues and water temperatures continue to rise.

“It’ll change the mix of species,” Tedesco said. “You had one species [lobsters] that were obviously important

to humans, but also helped structure the environment in the Long Island Sound. You lose that and there are other species that will take its place — and we’ll see that [happening] if waters continue to warm. Some species will get a competitive advantage over others.”

In a study conducted by the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection and the University of Connecticut from 1984 to 2008, it was proven — from tracking finfish in the Sound — water temperatures were causing warm water fish species to increase and cold water fish species to decrease. It also confirmed average catch in the spring has significantly decreased throughout the years — when the water is colder — while mean catch in the fall has increased, when the water is warmer.

“Collectively the abundance of cold-adapted species declined significantly over the time series in both spring and autumn,” the study found. “In contrast the abundance of warm-adapted species increased.”

The Connecticut research also said the trend in the Long Island Sound is consistent with trends and forecasts at larger biogeographic scales.

“Historic sea surface temperature data recorded from 1875 to 2007 show a significant warming trend along the U.S. coast north of Cape Hatteras [North Carolina] that exceeds local atmospheric temperature increases and is comparable to the warming rates of the Arctic,” the study continued. “It should be expected that the warming trend along the northeastern coast will continue.”

NYSDEC spokesperson Severino agreed North Shore water is rapidly warming.

“The western north Atlantic, Long Island Sound included, is one of the fastest warming places on the earth,” she said.

And the fishermen on Long Island may be discovering firsthand what a more powerful predatory species could do to diversity among fish in the Sound.

Black sea bass

“The problem is the predation from the black sea bass, we see lobster antenna in their mouths when we catch them,” Schneider said. “They’re expanding and spreading.”

His fellow North Shore fisherman agreed. “They’re eating everything — they eat juvenile everything,” Paterson said. “I would say [black sea bass] is 200 percent above even where they were last year.”

Severino, confirmed the warming water temperature in the Sound has played a part in the black sea bass population increase.

“Black sea bass are aggressive, highly opportunistic predators feeding on everything from amphipods to crabs to squid to fish.”

—Lori Servino

“Shifts in the distribution in the number of fish possibly associated with warming waters have been seen over the last decade,” she said in an email. “Generally, fish formerly associated with the Mid-Atlantic [area] are now more prominent in southern New England, including … the Long Island Sound. Black sea bass is an example of this.”

Severino also agreed black sea bass can be a formidable carnivore.

“Black sea bass are aggressive, highly opportunistic predators feeding on everything from amphipods to crabs to squid to fish,” she said. Further upstate in New York, the same changes in aquatic life are happening.

Hemlock forests, known for the shade and cool temperatures, have been declining due to an increase of an invasive insect population that’s thriving due to warmer winters. As hemlock habitats decline, so do New York state’s fish — and the brook trout that rely on that habitat.

“The loss of brook trout will cause changes in New York’s fishing economy and may have disproportionate effects on small, fishing-dependent communities in which millions of dollars are spent by tourists who come to fish for trout,” a study entitled “Responding to Climate Change in New York State” said. The report was carried out by Columbia University, CUNY and Cornell University for the state Energy Research and Development Authority. “Hunting, fishing and wildlife viewing make significant contributions to New York state’s economy. More than 4.6 million people fish, hunt or wildlife watch in the state, spending $3.5 billion annually.”

The future of the Long Island Sound remains uncertain, but in a warming climate the one thing guaranteed is change.