Nature Matters: A little night magic

By John L. Turner

Travis and I got our chairs positioned to be comfortable waiting for the show to begin. Facing west about a half hour after sunset on this July 4th evening, Venus dominated the sky shining brightly over a dark grey bank of clouds.

And then the show began, first a bright flash above us and to our left and then to our right and a third in the middle, higher still. And then several scattered across the sky in a triangle shape. A fireworks display to celebrate the holiday at a public park? Nope, a firefly display in our backyard!

Each night in early summer brings this show — free of charge — to a location near you, perhaps too in your backyard. It’s the annual mating flash of the firefly or as one prominent firefly expert calls it: “Silent love songs flashing their hearts out.” This yearly show is one of the joys of summer with so many childhoods having been enriched by children dashing to and fro temporarily capturing a few in a glass jar with some grass blades to watch the flashing fireflies up close. For us it’s fun to watch but for fireflies it involves the serious business of reproducing.

I remember a firefly display I witnessed about a decade ago at the NYSDEC’s Oak Brush Plains Preserve at Edgewood (located in Deer Park). I was there in the dark to listen for whip-poor-wills, the population of which might represent the westernmost breeding group remaining on Long Island. I headed into the property and broke north along a trail bordering an open meadow.

In the meadow were many fireflies and I do want to stress many — what had to number in the hundreds winking and flashing in and along the edges of the meadows. Some flashed while perched on the top of tall grass. There were so many fireflies I was mesmerized and after a few minutes of watching thousands of flashes and blinks I found it almost disorienting.

Fireflies are also known as lightning bugs but to be accurate they are neither flies nor bugs. Rather, they are beetles belonging to the family Lampyridae. (This is one of the few insect family names I’ve remembered by playing a little trick: these insects produce their own light just as lamps do.) Currently 173 species have been documented in North America with the majority occurring in the eastern half of the continent.

Staff from the New York Natural Heritage Program (NYNHP) have been assessing the diversity and abundance of fireflies in New York. According to Katie Hietala-Henschell, a zoologist with the state program, “27 species occur in NY” but believes the number will very likely increase, as she notes “there could potentially be 37 species.”

She further states: “For Long Island in particular, there are at least 10 species (probably more!) that have been documented. However, this is a very conservative estimate and likely an underestimate of the number of Long Island species.”

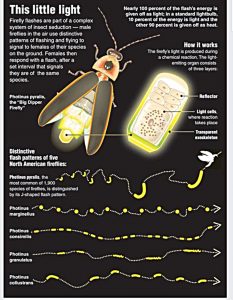

The most common species both in the eastern United States and here is Photinus pyralis commonly known as Common Eastern Firefly or the Big Dipper Firefly, probably due to its flash pattern appearing reminiscent of the well-known star pattern.

As for rare firefly species that may occur on Long Island, Katie indicates “The only documented IUCN Red List species that has occurred on Long Island is Photuris pensylvanica (Dot-dash Firefly) ranked as Vulnerable. … I suspect at least two other IUCN species that may occur on Long Island. It could be a long shot, but there is potential for Pyractomena ecostata (Keel-necked Firefly) ranked as Endangered and possibly Photuris bethaniensis (Bethany Beach Firefly) ranked as Critically Endangered by IUCN and petitioned to be federally listed as Endangered.”

As for rare firefly species that may occur on Long Island, Katie indicates “The only documented IUCN Red List species that has occurred on Long Island is Photuris pensylvanica (Dot-dash Firefly) ranked as Vulnerable. … I suspect at least two other IUCN species that may occur on Long Island. It could be a long shot, but there is potential for Pyractomena ecostata (Keel-necked Firefly) ranked as Endangered and possibly Photuris bethaniensis (Bethany Beach Firefly) ranked as Critically Endangered by IUCN and petitioned to be federally listed as Endangered.”

As I soon learned the dot-dash firefly is aptly named as its flash pattern consists of a short greenish colored flash (the dot) followed by a longer flash that lasts several seconds (the dash).

We have a pretty clear understanding of the underlying but complicated chemistry producing the magical flash in fireflies. Using organs in their abdomens, oxygen mixes with calcium, a chemical named luciferin, an enzyme — luciferase, and ATP (adenosine phosphate; remember this from the cellular biology you learned in high school?). Oxygen, the release of which fireflies can control, appears to be the “switch” that sets off the process. Nitric oxide gas also plays a role. This illumination is extremely efficient with the firefly giving off very little heat while emitting lots of bright light.

Their flash is an excellent example of bioluminescence — light made by living things. Bioluminescence is known across the living world — besides fireflies, a number of jellyfish, worms, squid (to be precise it’s the luminescent ink they shoot out to avoid predation), many fish species including deep-sea fish, algae, and fungi produce and emit light. There are approximately 1,500 species of fish alone that are bioluminescent!

In the category “the world is always more complicated than we think,” most female fireflies can’t fly since they lack wings or possess only vestigial wings, rendering them earthbound from where they flash (we know them as glowworms); the males of a few firefly species also cannot fly; and not all fireflies use flashing light to attract, with some employing scent attractants known as pheromones — species-specific chemicals that attract the opposite sex. And not all flashing is designed to entice mating. In some cases female fireflies mimic the male flash of other species to entice them so the females can dine on their bodies and incorporate the poisons contained within. A firefly femme fatale, if you will.

Fireflies, like so many insect species, are declining. Habitat loss and pesticide use are culprits. But perhaps the number one problem facing this iconic group of insects is excessive night lighting. As more homes are built and more of us leave front and back porch lights on, more ambient light is created, creating confusion for and competition to the flashing fireflies. This brightening glow of night lighting disorients migrating birds, dims the stars and the Milky Way, and, now, is having an adverse effect upon fireflies.

If you want to know what you can do to protect fireflies: Turn off outdoor lights as the lighting competes with the flashes of fireflies. Additionally, avoid using pesticides or chemical fertilizers and leave the leaves for the benefit of female fireflies and some firefly larvae which are found on the ground.

Here’s to hoping that fireflies make summertime memories for jar-carrying kids and their parents for countless summers to come.

A resident of Setauket, author John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

A resident of Setauket, author John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.