How the U.S. Made the Fateful Decision to Enter WWI

By Rich Acritelli

With the movie “1917” soon to be widely released in theaters, it’s interesting to look back on how Long Island was a key strategic reason the U.S. entered what was known as “the war to end all wars.”

Over 100 years ago, then President Woodrow Wilson agonized over the rationale for the United States to break with its historic policy of neutrality before America entered World War I against Germany. There were many dangerous periods within our history that surely tested our national leadership. This was no different in 1916-1917. At the end of his first term in office, Wilson sought economic and social reform in the U.S., but he had to contend with the terrible conflict over in Europe. Although the Atlantic Ocean separated the U.S. from the brutal fighting on both the eastern and western fronts, Long Islanders did not have to look far to identify the German military presence of U-boats that operated near their shores. During World War I and II, it was common for the U.S. government to order “light discipline” on the coast. German “Wolf Packs” operated near major cities like New York, surfaced, and were able to determine how close they were to the city by utilizing well-lit homes in waterfront locations like Fire Island. For three years, American ships operated within these hazardous waters to conduct trade with the Allies, where these vessels took heavy losses.

It was an extremely complicated time for Wilson, who tried to keep the country out of this war. The horrific losses seen by the British, French and Germans were well publicized in American papers, and many citizens did not want their sons, friends and neighbors to be killed in what was thought of as a European dispute. Before he was reelected by an extremely close margin in November of 1916, Wilson campaigned on the promise that he kept “Our boys out of this war.” But behind closed doors, it was a different situation. Since the days of George Washington the U.S. economy was built on trade that always saw American ships traveling to Europe. Germany had most of its own ports blockaded by the strength of the British navy, and this warring government did not believe America was neutral through our business dealings with the Allies.

The Germans believed they were forced to attack any civilian, commerce or military shipping that sailed toward British and French harbors. Wilson, like the presidents before the War of 1812, was unable to completely halt American maritime toward these hostile waters. Right away, cruise liners like the Lusitania was attacked off the coast of Ireland, and of the 1,198 people that were killed on the ship, 128 Americans were lost. The German government stated it gathered known intelligence that many of these civilian ships were carrying weapons to the Allies. As Wilson was expected to protect the American people, his own secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, opposed any offensive actions to arm U.S. ships or any threats toward the German leadership. In 1916, the Sussex was sunk, more American lives were lost, and Wilson was conflicted on how to respond against this German adversary who seemed unwilling to halt its policy of targeting American freedom of the seas.

Closer to home, in 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico, where 19 American lives were lost. With the tense relations between the U.S. and Mexico, Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to lead 16,000 soldiers to capture or kill Villa and his men. This U.S. expedition into Mexico demonstrated how unprepared the government was to conduct modern military operations. Pershing was unable to locate Villa within the Mexican terrain and the expedition was considered unsuccessful. This intervention also enhanced resentment by the Mexicans who gravitated closer to the Germans. The “Zimmerman telegram” by the German foreign minister openly stated that if Mexico went to war against the U.S., it would receive German assistance. These words were intercepted by the British and delivered to Wilson who was startled at the extent of German beliefs that Mexico had the ability to regain some of its lost territories that were now American states. Wilson’s fears were abundant, as he bolstered the U.S. defense of Cuba with an additional division of soldiers to guard against a possible German invasion.

Wilson was in a precarious situation, as there were known antiwar feelings against helping the British and French on the western front. During the election year, Wilson fully understood that the two largest immigrant groups in the country were the Irish and the Germans. He knew that some of these citizens had strong ethnic ties to their home countries and were not overly pleased to support the British Empire. While today we see Spanish as a common secondary language, during the early part of the 20th century, German was widely spoken in the Midwest and West. There was a huge German influence among American cities and towns that had ties back to this European power, and Wilson had to analyze the economic relation to this war of the many industrialists and financiers who looked to push the United States to support the Allies. They knew they could surely profit from the massive amount of weapons sold to these warring countries.

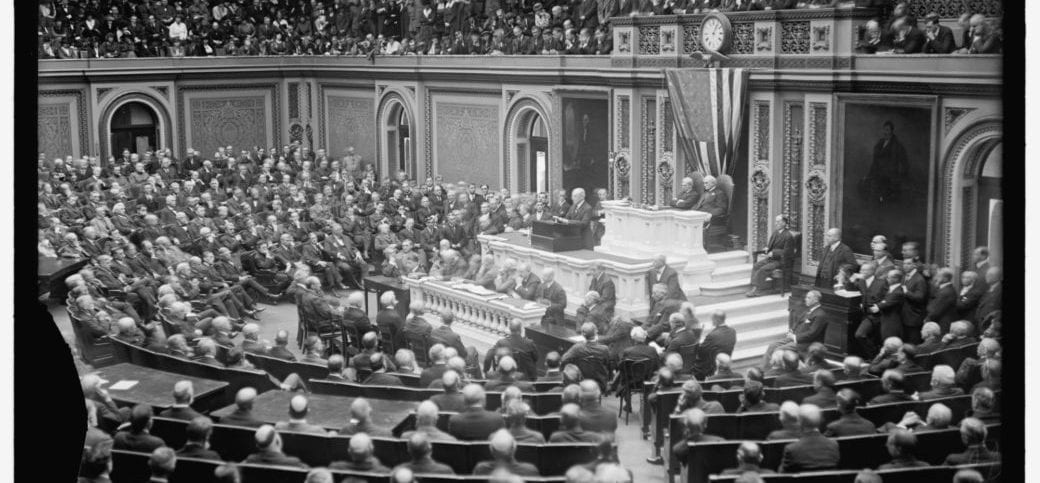

On the eastern front, there was the delicate situation with the ability of Czar Nicholas II to fight the Germans. His government’s conduct of the war was disastrous, and the Russians had abundant shortages of weapons, leadership and food at home. Before declaring war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Wilson watched Russia fall into chaos, as communist groups campaigned on the slogan that they were determined to quickly pull out of this destructive conflict. Although Wilson sided with the Allies and declared war against Germany, it was not without many internal strains. He was surely tested over the eventual American decision to abandon our foreign policy of neutrality that was established in 1789 to side with one European nation over another.

Rich Acritelli is a social studies teacher at Rocky Point High School and an adjunct professor of American history at Suffolk County Community College.