Your Turn: Curious things upon my book shelf

By John L. Turner

This is the second of a two-part series.

In part one of “Curious Books Upon My Bookshelf” (March 26 issue of Arts & Lifestyles) I focused on items I’ve collected through the years on walks along Long Island’s shoreline. In this part we go “inland” to discuss a few of Mother Nature’s gifts I’ve found while exploring Long Island’s fields and forests.

I like to stray off paths to “bushwhack” through a forest (a habit that has led me to meet more ticks than I’ve ever desired!), walking quietly, slowly and carefully in search of wildflowers, bird nests, snakes, box turtles and other objects of interest. It’s a bit like the method people use when walking around an old store filled with interesting antiques and nicknacks. If you do this (in the forest and not the store) it’s just a matter of time before you find one or more of these objects.

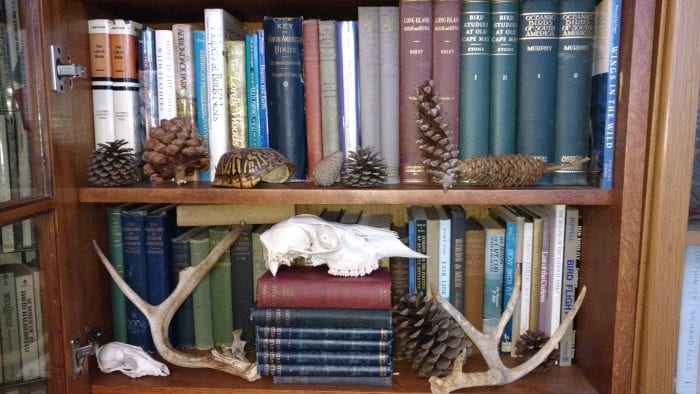

On numerous occasions I’ve come across the remains of a white-tailed deer — ribs, a pelvic girdle, vertebrae, sometimes skulls, but most often their shed antlers, laying amidst the leaves, slowly melting back into the earth. Their final resting spots are a solemn place and I invariably wonder what caused their death. Predator? (not yet at least, not until coyotes become more fully established on Long Island) Starvation? An accident? Succumbing to wounds from a hunting slug?I almost always don’t know.

Deer antlers are a thing of beauty; while they are generally variations on a central theme of a main shaft with arms or “points” emanating from it, each antler is unique. Grown and shed each year (unlike horns on a bison or bighorn sheep which are not shed but grow continuously throughout an animal’s lifetime), antlers generally get larger as the animal matures so an eight year buck will have a larger set of antlers than a three-year-old.

On occasion I’ll find an antler that has been extensively gnawed upon — this is not surprising. Antlers are composed of bone and contain calcium and minerals and a number of animals will take advantage of this prized “dietary supplement.” A four-state study to learn which animals eat antlers determined that grey squirrels most often gnawed on them; eleven species were tallied in all including, not surprisingly, other gnawing animals — chipmunks, rabbits, mice and woodchucks. A little more surprising were raccoons, coyotes, opossum, river otter and one beaver.

I occasionally encounter other mammal skulls besides deer. I have a few raccoon skulls, a woodchuck skull, a red fox skull, and my prized skull — that of a grey fox. This secretive and beautiful mammal is less well known than the more common red fox (the first grey fox I ever saw had climbed a persimmon tree in Maryland and was chowing down on tree ripe persimmons).

On Long Island I’ve been fortunate to have seen  live grey fox, the most recent experience in the autumn two years ago. Spying him before he saw me as I fortuitously was hidden behind a bushy, young Pitch Pine tree, this beautiful grizzled looking animal was patrolling along a sandy trail in the Dwarf Pine Plains of the Long Island Pine Barrens.

live grey fox, the most recent experience in the autumn two years ago. Spying him before he saw me as I fortuitously was hidden behind a bushy, young Pitch Pine tree, this beautiful grizzled looking animal was patrolling along a sandy trail in the Dwarf Pine Plains of the Long Island Pine Barrens.

Speaking of pines, pine cones are one of my favorite objects to collect; they adorn my shelves. Their varied but unifying symmetry is always a visual delight. I have many Pitch Pine cones, a few from White Pine, a Lodgepole Pine, a Norway Spruce, and even a Stone Pine from the west coast of Italy.

The smallest, most inconspicuous cone I have is my favorite though. It is a cone from a Pitch Pine but it doesn’t look like the other Pitch Pine cones I have; this one is a “closed” or “serotinous” pine cone from a dwarf pitch pine growing in the Dwarf Pine Plains on Long Island.

On tree-sized pitch pines the cones look like normal cones — as they mature the scales open up and the winged seeds flutter to the ground. But the pine cones that grow on the dwarf pine trees don’t typically open upon maturing. Rather, they remain resolutely closed, sometimes for decades — unless and until burned in a wildfire.

That this closed cone trait evolved with the dwarf pines makes sense because in a wildfire all of the dwarf stature trees are likely to burn, unlike in a forest of fifty-foot tall pines. If the pygmy pines had “normal” cones it is very likely all of the seeds would perish in a wildfire. The closed cones, however, protect the sensitive pine seeds inside the cone. It is a finely tuned system — the resins that hold the scales together in a serotinous cone melt in fire, allowing the scales to spread open over the course of hours, thereby releasing the seeds onto a forest floor with lots of available ash, nutrients, and sunlight — great conditions to start a new generation of dwarf pines in this fire-dependent forest.

The Dwarf Pine Plains, a globally rare part of the Long Island Pine Barrens, are situated in Westhampton. A circular interpretive hiking trail leads into the forest from the southern end of the parking lot of the Suffolk County Water Authority building located on the east side of County Route 31 about 200 yards south of the Sunrise Highway x County Route 31 intersection. That is where I saw the grey fox. If you go maybe you too will be lucky enough to see a fox sniffing in the sand in search of food!

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.