Valentine’s Day history in Three Village

By Beverly C. Tyler

The tradition of sending messages, gifts and expressions of love on Valentine’s Day goes back to at least the 15th century.

In 1477, in Britain, John Paston wrote to his future wife, “Unto my ryght wele belovyd Voluntyn – John Paston Squyer.”

The celebration of Feb. 14 began as an ancient Roman ceremony called the Feast of the Lupercalia, held each year on the eve of Feb. 15. It was on the eve of the Feast of the Lupercalia in the year 270 that Valentinus, a Roman priest, was executed.

According to a 1493 article in the Nuremberg Chronicle, “Valentinus was said to have performed valiant service in assisting Christian Martyrs during their persecution under Emperor Claudius II.”

Giving aid and comfort to Christians at that time was considered a crime, and for his actions, Valentinus was clubbed, stoned and beheaded. The Roman pagan festivals were spread all over the world as the Romans conquered various lands.

It is thought that when the early Christian church reorganized the calendar of festival, they substituted the names of Christian Saints for the pagan names and allocated Feb. 14 to St. Valentine. By the 17th century, Valentine’s Day was well established as an occasion for sending cards, notes or drawings to loved ones.

An early British Valentine dated 1684 was signed by Edward Sangon, Tower Hill, London.

“Good morrow Vallentine, God send you ever to keep your promise and bee constant ever.”

In America, the earliest known valentines date to the middle of the 18th century. These handmade greetings were often very artistically done and included a heart or a lover’s knot. Like letters of the period they were folded, sealed and addressed without the use of an envelope. Until the 1840s, the postal rate was determined by the distance to be traveled and the number of sheets included, so an envelope would have doubled the cost.

In 1840, Nichols Smith Hawkins of Stony Brook sent a valentine to his cousin Mary Cordelia Bayles. The original does not exist, but her reply, written two days after Valentine’s Day, says a great deal.

“I now take this opportunity to write a few lines to you to let you know that I received your letter last evening. I was very happy to hear from you and to hear that you hadent forgot me and thought enough of me to send me a Valentine. I havent got anything now to present to you but I will not forget you as quick as I can make it conveinant I will get something for you to remember me by. You wrote that you wanted me to make you happy by becoming yourn. I should like to comfort you but I must say that I cannot for particular reasons. It isn’t because I don’t respect you nor do I think that I ever shall find anyone that will do any better by me. I sincerely think that you will do as well by me as anyone. I am very sorry to hear that it would make you the most miserable wretch on earth if I refused you for I cannot give you any encouragement. I beg to be excused for keeping you in suspense so long and then deny you. Believe me my friend I wouldn’t if I thought of denying you of my heart and hand. I think just as much of you now as ever I did. I cannot forget a one that I do so highly respect. You will think it very strange then why I do refuse you. I will tell you although I am very sorry to say so it is on the account of the family. They do oppose me very much. They say so much that I half to refuse you. It is all on their account that I do refuse so good an offer.”

Four days later, Mary again replied to a letter from Nichols.

“Dear Cousin – I received your letter yesterday morning. I was very sorry to hear that you was so troubled in mind. I don’t doubt but what you do feel very bad for I think that I can judge you by my own feelings but we must get reconciled to our fate … Keep your mind from it as much as you can and be cheerful for I must tell you as I have told you before that I cannot relieve you by becoming your bride, therefore I beg and entreat on you not to think of me anymore as a companion through life for if you make yourself unhappy by it, you will make me the most miserable creature in the world to think that I made you so unhappy.“

At least two other letters, written the following year, were sent to Nichols from Mary. The letters continued to express the friendship that existed between them. The story does not end at this point. Mary’s father died in 1836 and her mother in 1838, and it is possible that she lived for a time with her aunt Elizabeth and uncle William Hawkins — Nichols’ parents.

Whatever the circumstances that brought them together, their love for each other continued to bloom.

On Feb. 11, 1849, Nichols Smith Hawkins, age 34 married Mary Cordelia Bayles, age 27. Nichols and Mary raised three children who lived beyond childhood — two others died in 1865 within a month.

Nichols was a farmer and the family lived in Stony Brook. Mary died in 1888 at the age of 66 and Nichols died in 1903, at the age of 88. They are buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Stony Brook.

Valentines became fancier and more elaborate through the second half of the 19th century. After 1850 the valentine slowly became a more general greeting rather than a message sent to just one special person.

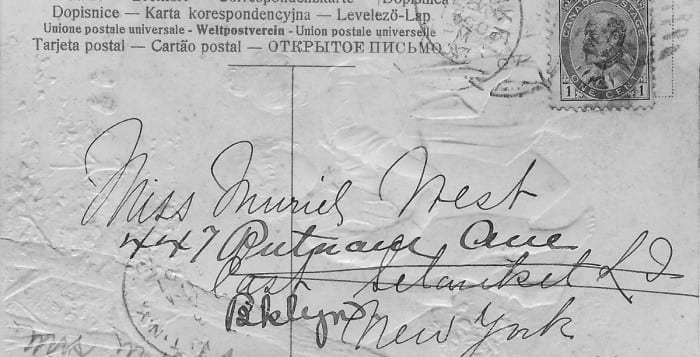

The advent of the picture postal card in 1907, which allowed messages to be written on one half of the side reserved for the address, started a national craze that saw every holiday become a reason for sending a postcard and Valentine’s Day the occasion for a flood of one cent expressions of love.

Beverly Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the Three Village Historical Society.