By Beverly C. Tyler

“Roots,” a new version and a new vision.

This past week the cable channels History, A&E and Lifetime presented a new look at Alex Haley’s 1976 novel, which tells the story of his Mandinka ancestor Kunta Kinte and his descendants. Born in the village of Juffure, West Africa, in 1750, Kunta Kinte and other Mandinka men and women were captured, transported to America and there suffered brutal enslavement. In 1977 “Roots” became an ABC network miniseries watched by millions of viewers. It was a slavery story that many Americans were learning for the first time. Now a new generation of Americans, sadly less informed about our history, can benefit from this new adaptation of Haley’s historical novel.

“Roots,” 2016, benefits from new scholarship giving viewers a broader understanding of the Mandinka culture in which Kunta Kinte grew to manhood, factors that led to a culture of enslavement by the Africans themselves, and the brutal conditions on the British and Americans ships that transported Africans to the Americas. The story continues in America with a more detailed story of the enslaved Africans and less about the white slavers and plantation owners than in the 1977 ABC miniseries.

If you missed the original production last week, you will be able to see it repeated on the cable channels or on the web at https://roots.history.com/. The Web site also includes more details on the show and on the featured characters and actors.

On a more local level, the book, “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory,” by Anne Farrow uses a log book of three voyages, over 20 months in the first half of the 18th century, recorded by a young Connecticut man who went on to captain slave ships and privateers, to tell a much wider and disturbing story.

Farrow’s book connects Dudley Saltonstall, the Connecticut man who kept the log books, to the slaves transported from Africa, then to the African men who enslaved them, to the ships that transported them across the Atlantic, and finally to the men who purchased them to work to death in the Caribbean sugar plantations and rice plantations of America’s southern colonies.

Farrow, a former Connecticut newspaper reporter, feels the early story of African people in America must be told over and over, from the beginning. She believes that it has not yet been absorbed into the family of stories told and retold about America, that the story of injustice and suffering still has not made its way into the national narrative.

Unknown to most Americans is the fact that colonial Connecticut was a major provisioner of British West Indies plantations where slaves were growing and processing sugar and yielding huge profits. In addition, Rhode Island men were at the helm of 90 percent of ships that brought captives to the American south, an estimated 900 ships.

The story of the Connecticut and Long Island Sound men who took part in the slave trade is disturbingly real. It brings into focus the way many of our own prosperous and influential Long Island families made their fortunes. It doesn’t change who they were or who we are, but it provides us with a clearer understanding of the pain and suffering caused by their actions.

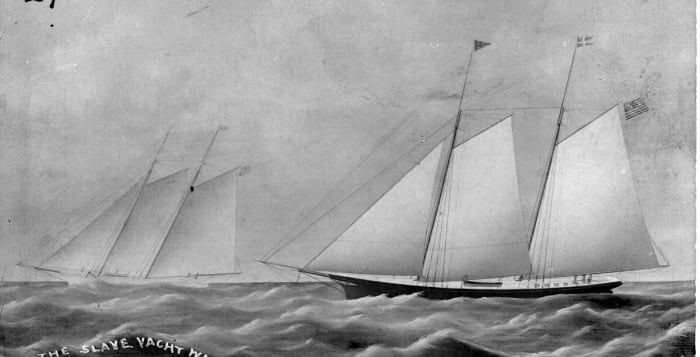

In spite of the federal law (1807) prohibiting the importation of slaves from Africa, slaves were still being transported from Africa until the beginning of the American Civil War. On an even more local level is the story of our own East Setauket slave ship, Wanderer.

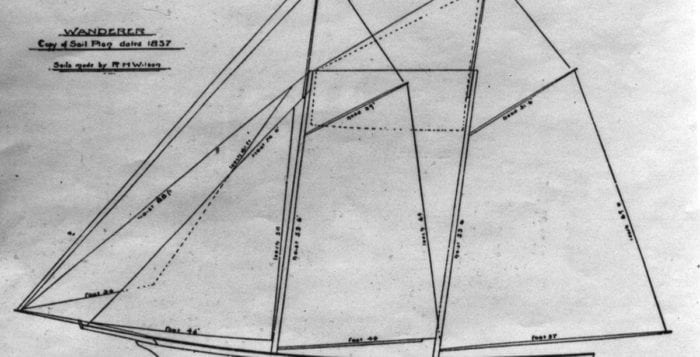

East Setauket’s Joseph Rowland built the schooner-yacht Wanderer in 1857 for Colonel John D. Johnson, a New York Yacht Club member and a wealthy New Orleans sugar planter. The sails for the Wanderer were made in Port Jefferson in the Wilson Sail Loft.

Johnson sold the Wanderer in 1858 to William Corey, and she reappeared in Port Jefferson where large water tanks were installed. Despite numerous checks by the U.S. Revenue Service the Wanderer was allowed to sail.

Slavers were rigged to outrun the slave squadrons of Great Britain and America, both of which were trying to stop the now illegal slave trade. Wanderer took aboard some 600 people from the west coast of Africa and sailed for America.

On Nov. 28, 1858, she landed 465 Africans on Jekyll Island, Georgia. The ship was seized by federal authorities; however, the Africans, now on Georgia soil, a slave state, were sold at auction.

A walking tour of the maritime and wooden shipbuilding area along Shore Road in East Setauket will be conducted Saturday, June 18, beginning at 3 p.m. from the Brookhaven Town Dock for a tour of the homes and shipyards that built ships that sailed around the world. The tour includes the home of the Wanderer shipbuilder and his story.

Beverly Tyler is the Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the Three Village Historical Society.