By Daniel Dunaief

Paintings can be so evocative that they bring images and scenes to life, filling a room with the iridescent flowers from an impressionist or inspiring awe with a detailed scene of human triumph or conflict. While the paints themselves remain inanimate objects, some of them can change over time, as reactions triggered by anything from light to humidity to heat can alter the colors or generate a form of soap on the canvas.

Recently, a team led by Silvia Centeno, a research scientist of the Department of Scientific Research at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, explored the process that caused lead-tin yellow type I to form an unwanted soap. Soap formation “may alter the appearance of paintings in different ways, by increasing the transparency of the paints, by forming protrusions that may eventually break through the painting surface, or by forming disfiguring surface crusts,” Centeno explained in an email.

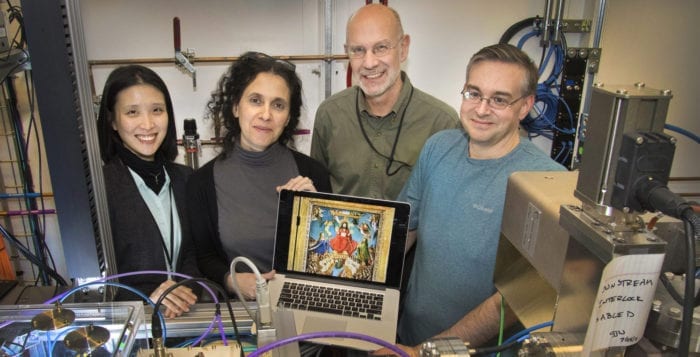

A team that included Karen Chen-Wiegart, who is an assistant professor at Stony Brook University and has a joint appointment at Brookhaven National Laboratory, looked specifically at what caused a pigment common in numerous paintings to form these soaps. The research proved that the main component in lead-tin yellow pigment reacts, Centeno said. The causes may be environmental conditions and others that they are trying to discover. Lead-tin yellow changes its color from yellow to a transparent white. The pigment was widely used in oil paintings.

The pigment hasn’t shown the same deterioration in every painting that has the reactive ingredients, which are heavy-metal-containing pigments and oil. This suggests that specific environmental conditions may contribute to the pace at which these changes occur. Most of the time, the changes that occur in the paintings are below the surface, where it may take hundreds of years for these soaps to form.

The scientists are hoping this kind of research helps provide insights that allow researchers to protect works of art from deterioration. Ideally, they would like a prognostic marker that would allow them to use noninvasive techniques to see intermediate stages of soap formation. That would allow researchers to follow and document change through time. The scientists analyzed a microscopic sample from the frame of a painting from Jan Van Eyck called “Crucifixion,” which was painted in 1426.

Samples from works of art are small, around several microns, and are usually removed from areas where there is a loss, which prevents any further damage. Samples are kept in archives where researchers can do further analysis. In this case, a microscopic sample was taken from the frame of the painting, from an area where there was already a loss.

Centeno worked with a group led by Cecil Dybowski, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Delaware, who has used solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy available at the university to study soap formation since 2011.

She also partnered with Chen-Wiegart to work at BNL’s National Synchrotron Light Source II, a powerful tool with numerous beamlines that can see specific changes on an incredibly fine scale. Centeno said she was very pleased to add Chen-Wiegart’s expertise, adding that she is “an excellent collaborator.”

When they started working together, Chen-Wiegart worked at BNL as an assistant physicist, and then became an associate physicist. As a beamline scientist, she worked at a beamline led by Juergen Thieme, who is a collaborator on this project as well. The researchers see this as an initial step to understand the mechanism that leads to the deterioration of the pigment.

The team recently applied for some additional beamline time at the NSLS-II, where they hope to explore how porosity, pore size distribution and pore connectivity affect the movements of species in the soap formation reactions. The humidity may have more impact in the soap formation. The researchers would like to quantify the pores and their effects on the degradation, Chen-Wiegart said.

In addition, Centeno plans to prepare model samples in which she accelerates the aging process, to understand, at a molecular level, what might cause deterioration. She is going to “try to grow the soaps in the labs, to see and study them with sophisticated techniques.”

Chen-Wiegart will also study the morphology at microscopic and macroscopic levels from tens of nanometers to microns. Both Centeno and Chen-Wiegart are inspired by the opportunity to work with older paintings. “I feel fortunate to have the opportunity to enjoy works of art as part of my daily work,” Centeno said.

Chen-Wiegart was eager to work with art that was created over 500 years ago. “The weight of history and excitement of this connection was something enlightening,” she said. “Thinking about it and processing it was a unique experience.”

A resident of Rocky Point, Chen-Wiegart lives with her husband Lutz Wiegart, who is a beamline scientist working at the Coherent Hard X-ray Scattering beamline at BNL. People assume the couple met at BNL, but their relationship began at a European synchrotron called ESRF in France, which is in Grenoble.

The couple volunteers at the North Shore Christian Church in Riverhead in its Kids Klub. For five days over the last five summers, they did science experiments with children who are from 4 to 11 years old.

The scientific couple enjoys the natural beauty on Long Island, while traveling to the city for cultural events. They kayak in the summer and visit wineries.

As for her work, Chen-Wiegart is excited about continuing her collaboration with Centeno.“The intersection between science, art and culture is inspiring for me.”