By Daniel Dunaief

An increasingly complex time filled with extreme stressors such as man-made and natural disasters creates conditions that can lead to post traumatic stress disorder.

PTSD, which can cause anxiety even amid safer conditions, can have adverse effects on the ability to enjoy life.

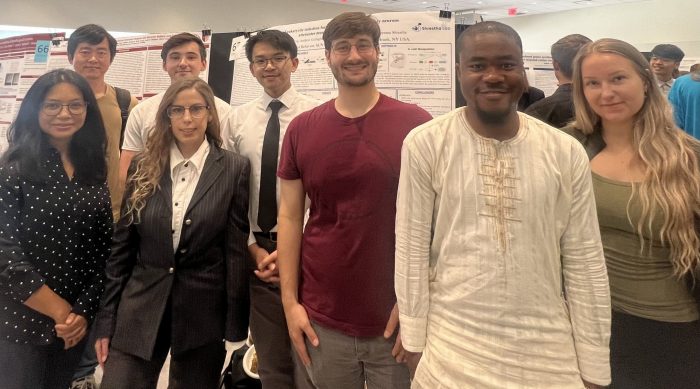

Stony Brook University Assistant Professor Prerana Shrestha, who joined the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at the Renaissance School of Medicine in 2021, recently received a four-year $2.2 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to study the molecular mechanisms underlying stabilization of emotional memories in the brain, which is relevant for PTSD.

“Her work will help us understand how the brain stores these traumatic memories,” said Alfredo Fontanini, chair of the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior. “The tools she has developed really are making possible a series of experiments that, before, were impossible to think about.”

Shrestha hopes to develop a druggable target that could “block a key machine inside neurons that are relevant for traumatic emotional memories,” she explained.

Using a mouse model, Shrestha plans to understand the neural signature at the level of molecules, neurons, and neural circuits, exploring the creation and stabilization of these potentially problematic memories and emotional reactions through a multi-disciplinary study.

Shrestha has developed and applied chemogenetic tools to block a key part of the memory process inside neurons that store traumatic emotional memories.

By developing tools to explore neural circuits in particular areas of the brain, Shrestha can help scientists understand the molecular mechanism involved in PTSD, Fontanini said.

‘From the ground up’

In humans, memories from traumatic events are over consolidated, creating an excessive avoidance behavior that can be a debilitating symptom.

“We are trying to understand the neurological basis for why these memories are so robust,” Shrestha said. She is looking at “what can we do to understand the mechanism that supports these memories from the ground up.”

With her chemogenetic tools, Shrestha can block protein synthesis in specific neuron populations in a time period of a few hours. She is developing new tools to improve the precision of blocking the protein synthesis machinery from hours to minutes.

Shrestha is trying to weaken the salient emotional memory while leaving all other processes intact.

The Stony Brook Assistant Professor said she has methods to create a targeted approach that limits or minimizes any off target or collateral damage from inhibiting the synthesis of proteins.

“Up until now, whenever scientists wanted to study the role of the synthesis of new proteins in memory formation” including those involved in the formation of aberrant memories such as those in PTSD, they had to “use drugs which would manipulate and affect protein synthesis everywhere in the brain,” said Fontanini.

The plan over the next four years is to understand and develop molecules to target cells in the prefrontal cortex, which, Shrestha said, is like the “conductor of an orchestra,” providing top-down executive orders for the brain.

She is focusing on neurons that interact specifically with the amygdala, which is the emotional center of the brain, exploring what happens in these streams of information between brain regions.

By increasing or reducing protein synthesis in the prefrontal cortex, Shrestha can see an enhanced or diminished avoidance response in her mouse experiments.

She is interested in how a memory is stabilized, and not as much in what is involved in its retrieval.

Shrestha works with inbred mice that are more or less genetically identical. Her experimental group has the transgenic expression of the chemogenetic tool to block protein synthesis and receive a drug after learning that triggers the tool to block the machinery from making new proteins.

When she introduces the inhibitor of protein synthesis, she found that the wave involved in stabilizing what the animal previously learned is finite in time.

Using a drug to block protein synthesis within an hour alters future behavior, with the animal showing little or no fear. Blocking protein synthesis after that hour, however, doesn’t affect the fear response.

In the first year of the grant, which started in December, Shrestha would like to send out some papers for publication based on the research her team members — postdoctoral researcher Sunghoon Kim and graduate student Matthew Dickinson — has already done. She also hopes to use some of the funds from this grant to hire another postdoctoral researcher to join this effort.

She has data on how the regulators of ribosomes are recruited in the prefrontal cortex, which stabilizes memories.

In other preliminary data, she has identified neurons in the prefrontal cortex that project into the amygdala that are selectively storing information for recent parts of emotional memory.

To be sure, while this research offers a potential window into the mechanisms involved in forming emotional memories in a mouse model, it is an early step before even considering any new types of diagnostics or treatment for humans.

Nepal roots

Born and raised in Kathmandu, Nepal, Shrestha received a full scholarship to attend Bates College, in Maine, where she majored in biological chemistry. She received a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fellowship for an internship at Harvard Medical school during her junior year. While preparing for a pre-medical track, she “got spoiled after getting a taste of research in my junior year,” she said. “The idea of trying something new for the first time and seeing how things work was so cool.”

Shrestha lives about eight miles west of Stony Brook and is married to Sameer Maskey, the founder and CEO of an advanced machine learning company called FuseMachines Inc. They have a nine-year old daughter and a two-year-old son.

As for her ongoing work, Shrestha is eager to combine her expertise with those of people from different backgrounds. “It’s a fascinating time to combine molecular approaches,” she said.

Fontanini, who helped recruit Shrestha, has been impressed with the work she’s done.

“She’s on an outstanding trajectory,” he said.

Operation-Initiative Foundation will present a Holistic Healing Workshop for Veterans with PTSD and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury at Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church, 716 Route 25A, Rocky Point on Saturday, April 14 from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. This event will feature speakers that will address the advances made in their respective disciplines and in Complementary and Alternative Medicine that are at the forefront in treating veterans who have been diagnosed as having PTSD. Additional discussion will focus on supportive needs of their family caregivers. All veterans and caregivers should bring a copy of their DD 214. All information is kept completely confidential. Seating is limited and lunch will be provided. To reserve your spot, call 631-744-9355.

Operation-Initiative Foundation will present a Holistic Healing Workshop for Veterans with PTSD and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury at Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church, 716 Route 25A, Rocky Point on Saturday, April 14 from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. This event will feature speakers that will address the advances made in their respective disciplines and in Complementary and Alternative Medicine that are at the forefront in treating veterans who have been diagnosed as having PTSD. Additional discussion will focus on supportive needs of their family caregivers. All veterans and caregivers should bring a copy of their DD 214. All information is kept completely confidential. Seating is limited and lunch will be provided. To reserve your spot, call 631-744-9355.