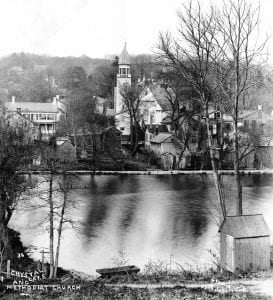

Cedar Hill Cemetery is located in Port Jefferson on a commanding site high above the village’s downtown and harbor.

Among those at rest in the cemetery, there are over 40 soldiers and sailors who served with the North during the Civil War.

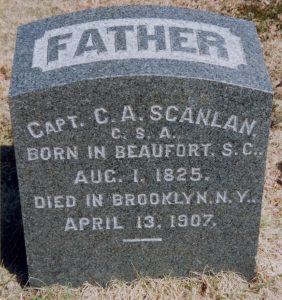

Capt. C. A. Scanlan is also buried in the cemetery, but he fought against the Union forces in the South’s Lost Cause. His tombstone is inscribed with “C.S.A.,” the initials representing the Confederate States of America.

Who was this former Rebel officer and how did he become one of Port Jefferson’s permanent residents?

Charles Anthony Scanlan was born in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1825. Married twice, he had a daughter with his first wife.

Scanlan worked as a shipsmith on the docks in Charleston, South Carolina, worshipped at the city’s First Baptist Church, was a Freemason, and belonged to the local militia.

Photo by Kenneth C. Brady

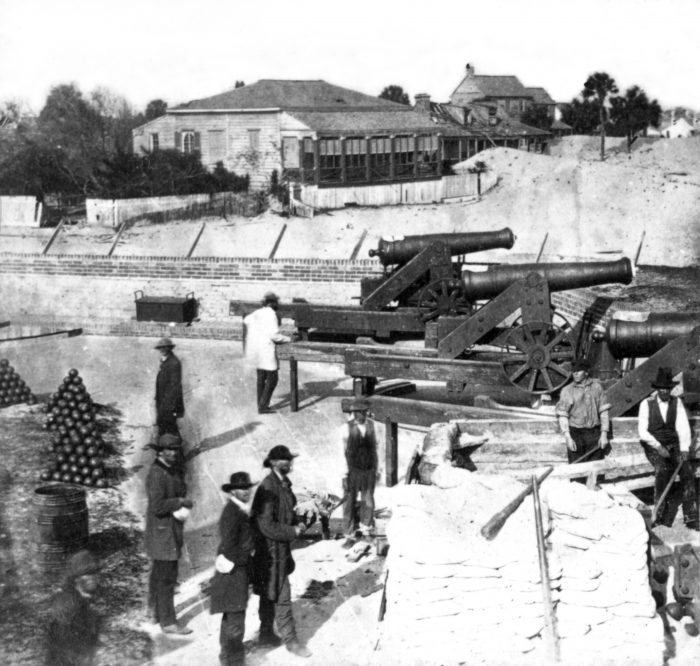

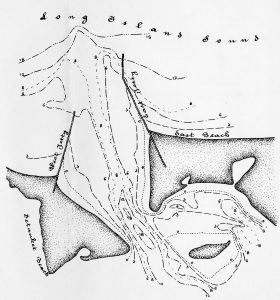

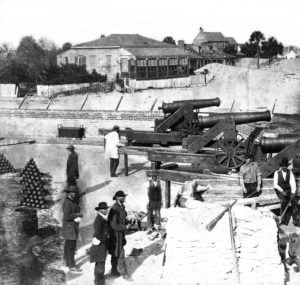

After South Carolina seceded from the Union, Federal troops transferred from the garrison at Fort Moultrie to the stronger Fort Sumter, both part of Charleston’s harbor defenses. Scanlan was among the Carolinians who then occupied the abandoned Fort Moultrie.

Scanlan began his duties at the emplacement on Jan. 1, 1861, served as an acting military storekeeper and readied the stronghold’s guns and ordinance for what would become the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

The action began on April 12, 1861, when a ring of Confederate batteries around Charleston Harbor hammered Fort Sumter, the barrage announcing the start of the Civil War. Described as a “sergeant” in a later account of the assault, Scanlan led a detachment of six men in Fort Moultrie’s magazine, one of the emplacements blasting the Union forces

Following the evacuation of the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter, Scanlan was assigned to Fort Walker on South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island. In official accounts of the battle, Scanlan was identified as a “lieutenant” and commended for his work in the citadel’s magazine.

After tours at South Carolina’s Castle Pinckney and Fort Beauregard, Scanlan was assigned to Fort Sumter, where he was wounded in August 1863 during the Union’s bombardment of the Confederate stronghold.

Scanlan ended his days in the military as a captain. He returned to Charleston where he resumed his work as a shipsmith, later pursuing an entirely new career.

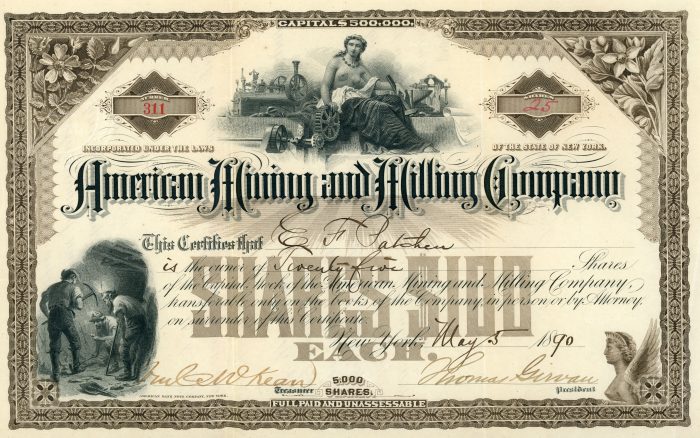

Phosphate rocks, which existed in large quantities near Charleston, were used in the manufacture of commercial fertilizer. Scanlan fabricated machinery that improved the dredging of the valuable rock from South Carolina’s riverbeds. Securing patents on his inventions in 1877 and 1883, Scanlan profited handsomely from the extensive phosphate digging in the Ashley River region.

During the mining operations, fossils were found in the phosphate deposits. Fascinated with natural history, Scanlan began gathering the specimens, amassing the largest private collection of fossils in South Carolina and among the largest in the nation.

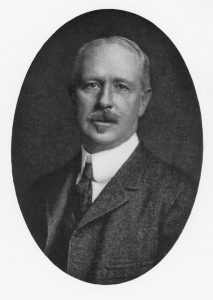

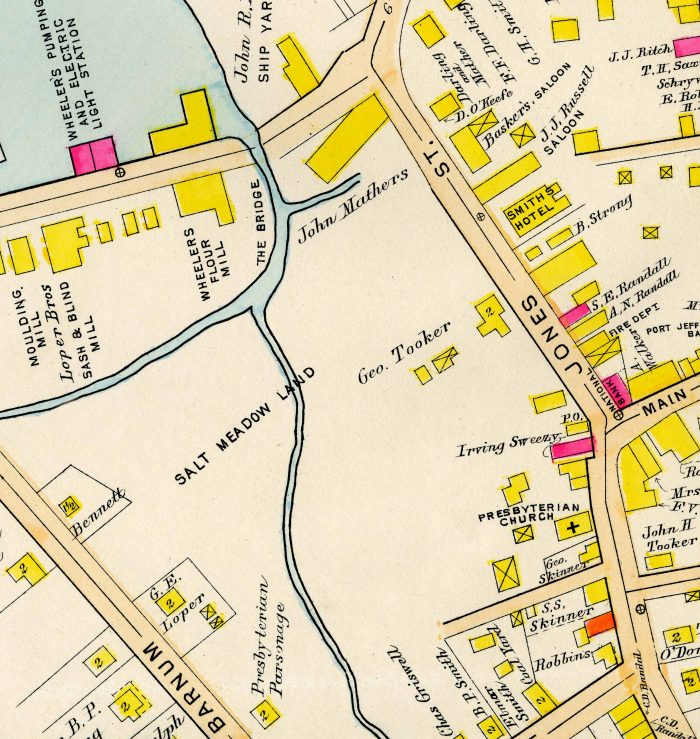

Following the death of his second wife Eliza in 1890, Scanlan moved to Port Jefferson to live with his daughter Mary Estelle who had married Henry Randall, a prominent Port Jefferson businessman and banker.

The Randalls spent summers at their house on Port Jefferson’s Myrtle Avenue and winters at their home in Brooklyn, with the elder Scanlan joining in the seasonal move.

Scanlan quickly became well-known in Port Jefferson. In 1893, he exhibited portions of his fossil collection at the village’s Athena Hall (Theatre Three) and later in many of Port Jefferson’s storefronts.

But two events brought Scanlan even wider acclaim. His fossils were displayed at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and at the Agricultural Palace during the Charleston Exposition, both shows earning Scanlan rave reviews for his superb collection.

Besides providing his fossils for public viewing, Scanlan donated items from his collection to universities and museums in the United States and abroad, where paleontologists used the specimens in their studies of early forms of life.

Growing older, Scanlan reflected on his years in the military, thinking that at the time of the Civil War he had been “in the right” to support disunion, but later coming to believe he had fought in a “mistaken cause.”

Although he had once worn Confederate Gray, Scanlan was treated respectfully in Port Jefferson by his former foes. During Decoration Day ceremonies at Cedar Hill Cemetery in May 1905, he was among those honored by Lewis O. Conklin Post 627, Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Union veteran organization with a “camp” in the village.

Scanlan died in Brooklyn in 1907. Following Baptist services held at his son-in-law’s Port Jefferson home, Scanlan was buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery.

In 1913, Scanlan’s massive collection of fossils, amounting to over nine barrels of diggings, was sold by his estate to Connecticut’s Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History where Scanlan’s legacy lives on.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as s well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.