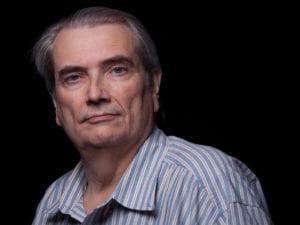

By Daniel Dunaief

Michael Schatz, Adjunct Associate Professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, saw some similarities to his own life when he met the then 14-year old Aspyn Palatnick.

Palatnick, who was a student at Cold Spring Harbor High School, had been developing games for the iPhone. When he was that age, Schatz, who is also a Bloomberg Distinguished Associate Professor of Computer Science and Biology at Johns Hopkins University, stayed up late into the evening programming his home computer and building new software systems.

Meeting Palatnick eight years ago was a “really special happenstance,” Schatz said. He was “super impressed” with his would-be young apprentice.

When he first met Schatz, Palatnick explained in an email that he “realized early on that he would be an invaluable mentor across research, computer science, and innovation.”

Palatnick was looking for the opportunity to apply some of the skills he had developed in making about 10 iPhone games, including a turtle racing game, to real-world problems.

Knowing that Palatnick had no formal training in computer science or genetics, Schatz spent the first several years at the white board, teaching him core ideas and algorithms.

“I was teaching him out of graduate student lecture notes,” Schatz said.

Schatz and Palatnick, who graduated with a bachelors and master’s from the University of Pennsylvania and works at Facebook, have produced a device which they liken to a “tricorder” from Star Trek. Using a smart phone or other portable technology, the free app they created called iGenomics is a mobile genome sequence analyzer.

The iPhone app complements sequencing devices Oxford Nanopore manufactures. A mobile genetic sequencer not only could help ecologists in the field who are studying the genetic codes for a wide range of organisms, but it could also be used in areas like public health to study the specific gene sequences of viruses like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19.

In a paper published in GigaScience, Schatz and Palatnick describe how to use iGenomics to study flu genomes extracted from patients. They also have a tutorial on how to use iGenomics for COVID-19 research.

While developing the mobile sequencing device wasn’t the primary focus of Schatz’s work, he said he and others across numerous departments at Johns Hopkins University spent considerable time on it this summer, as an increasing number of people around the world contracted the virus.

“It very rapidly became how I was spending the majority of my time,” said Schatz.

Palatnick is pleased with the finished product.

“We’ve made DNA sequence analysis portable for the first time,” he explained in an email.

Palatnick said the app had to use the same algorithms as traditional genomics software running on supercomputers to ensure that iGenomics was accurate and practical. Building algorithms capable of rendering DNA alignments and mutations as users tapped, scrolled and pinched the views presented a technical hurdle, Palatnick wrote.

While Schatz is optimistic about the vaccinations that health care workers are now receiving, he said a mass vaccination program introduces new pressure on the virus.

“We and everyone else are watching with great interest to see if [the vaccinations] cause the virus to mutate,” Schatz said. “That’s the big fear.”

Working with the sequences from Nanopore technology, iGenomics can compare the entire genome to known problematic sequences quickly. Users need to get the data off the Oxford Nanopore device and onto the app. They can do that using email, from Dropbox or the web.

In prior viral outbreaks, epidemiologists traveled with heavier equipment to places like West Africa to monitor the genome of Ebola or to South and Central America to study the Zika virus genome.

“There’s clearly a strong need to have this capability,” Schatz said.

Another iGenomics feature is that it allows users to airdrop any information to people, even when they don’t have internet access.

Schatz urged users to ensure that they use a cloud-based system with strong privacy policies before considering such approaches, particularly with proprietary data or information for which privacy is critical.

As for COVID-19, people with the disease have shown enough viral mutations that researchers can say whether the strain originated in Europe or China.

“It’s kind of like spelling mistakes,” Schatz said. “There are enough spelling mistakes where [researchers] could know where it came from.”

Palatnick described iGenomics as an “impactful” tool because the app has increased the population of people who can explore the genome from institutional researchers to anyone with an iPhone or iPad.

In the bigger picture, Schatz is broadly interested in learning how the genome creates differences.

“It’s important to understand these messages for the foods we eat, the fuels we use, the medicines we take,” Schatz said. “The next frontier is all about interpretation. One of the most powerful techniques is comparing one genome to another.”

Schatz seeks out collaborators in a range of fields and at numerous institutions, including Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Schatz and W. Richard McCombie, Professor at CSHL, are studying the genomes of living fossils. These are species that haven’t evolved much over millions of years. They are focusing on ancient trees in Australia that have, more or less, the same genetic make up they did 100 million years ago.

As for Palatnick, Schatz described his former intern and tricorder creating partner as a “superstar in every way.” Schatz said it takes considerable fortitude in science, in part because it takes years to go from an initial idea on a napkin to something real.

Down the road, Schatz wouldn’t be surprised if Palatnick took what he learned and developed and contributed to the founding of the next Twitter or Facebook.

“He has that kind of personality,” Schatz said.