A new biomedical research tool that enables scientists to measure hundreds of functional proteins in a single cell could offer new insights into cell machinery. Led by Jun Wang, Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Stony Brook University, this microchip assay — called the single-cell cyclic multiplex in situ tagging (CycMIST) technology – may help to advance fields such as molecular diagnostics and drug discovery. Details about the cyclic microchip assay method are published in Nature Communications.

While newer technologies of single-cell omics (ie, genomics, transcriptomics, etc.) are revolutionizing the study of complex biological and cellular systems and scientists can analyze genome-wide sequences of individual cells, these technologies do not apply to proteins because they are not amplifiable like DNAs. Thus, protein analysis in single cells has not reached large-scale experimentation. Because proteins represent cell functions and biomarkers for cell types and disease diagnosis, further analysis on a single-cell basis is needed.

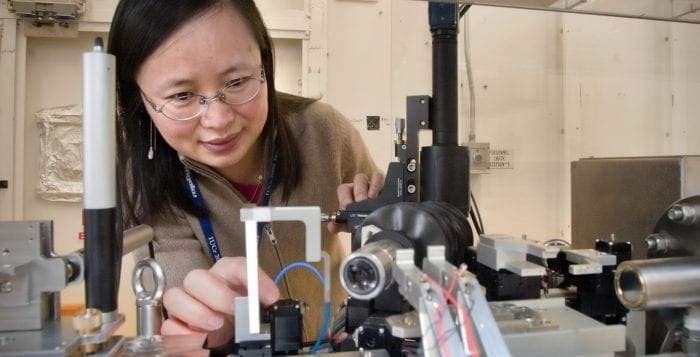

“The CycMIST assay enables comprehensive evaluation of cellular functions and physiological status by examining 100 times more protein types than conventional immunofluorescence staining, which is a distinctive feature not achievable by any other similar technology,” explains Liwei Yang, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar within the Wang research team and Multiplex Biotechnology Laboratory.

Wang, who is affiliated with the Renaissance School of Medicine and Stony Brook Cancer Center, and colleagues demonstrated CycMIST by detecting 182 proteins that include surface markers, neuron function proteins, neurodegeneration markers, signaling pathway proteins and transcription factors. They used a model of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in mice to validate the technology and method.

By analyzing the 182 proteins with CycMIST, they were able to perform a functional protein analysis that revealed the deep heterogeneity of brain cells, distinguished AD markers, and identified AD pathogenesis mechanisms.

With this detailed way to unravel proteins in the AD model, the team suggests that such functional protein analysis could be promising for new drug targets for AD, for which there is not yet an effective treatment. And they provide a landscape of potential drug targets at the cellular level from the CycMIST protein analysis.

The authors believe that CycMIST could also have enormous potential for commercialization.

They say that before this study model with CycMIST, researchers could only measure and know a tip of protein types in a cell. But this new approach enables scientists to identify and know the actions of each aspect of a cell, and therefore they can potentially identify if a cell is in a disease status or not – the first step in a possible way to diagnose disease by analyzing a single protein cell. And compared with standard approaches like flow cytometry, their approach with CycMIST can analyze 10 times the amount of proteins and on a single-cell level.

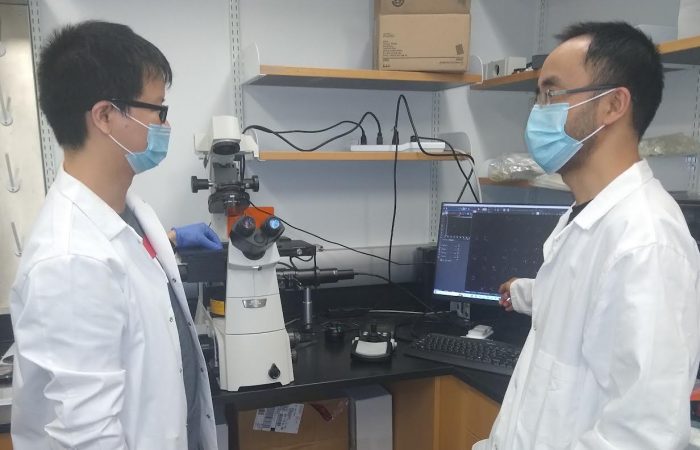

The researchers also suggest that the cyclic microchip assay is portable, inexpensive, and could be adapted to any existing fluorescence microscope, which are additional reasons for its marketability if it proves to be effective with subsequent experimentation.

Much of the research for this study was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Aging (grant # R21AG072076), other NIH grants, and a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant.