They named it Apollo. Though the moniker has become synonymous with human achievement, a scientific milestone, the merging of a collective national conscience, the Greek god Apollo was known for many things, but the moon was not one of them. If scientists had to choose, there was the Titan Selene, or perhaps Artemis or Hecate, all Greek gods with connection to the great, gray orb in the night’s sky.

Abe Silverstein, NASA’s director of Space Flight Programs, proposed the name, and he did so beyond the surface of using a well-known god of the pantheon. In myth, Apollo was the sky charioteer, dragging Helios, the Titan god of the sun, in an elliptical high over humanity’s head.

If anything was going to bring humanity to the moon, it would be Apollo.

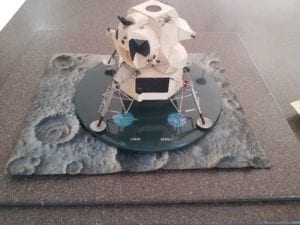

Despite this, it wasn’t a myth that allowed man to take his first steps on the moon, it was humankind. Billions of dollars were spent by companies across the nation, working hand in hand with NASA to find a way to make it into space. Here on Long Island, the Bethpage-based Grumman Corporation worked to create the lunar module, the insect-looking pod that would be the first legs to test its footing on the moon’s surface.

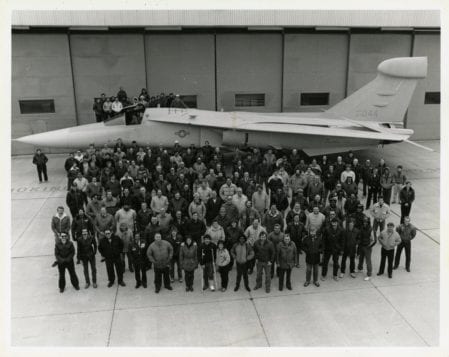

Thousands worked on the lunar module, from engineers to scientists to accountants to everyone in between.

Half a century later some of these heroes of science, engineers and other staff, though some may have passed, are still around on the North Shore to continue their memories.

Pat Solan — Port Jefferson Station

By Kyle Barr

Pat Solan of Port Jefferson Station can still remember her late husband, Mike, back when the U.S. wanted nothing more than to put boots far in the sky, on the rotating disk of the moon.

Mike worked on the Apollo Lunar Module at Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, where he was at the head of several projects including mock-ups of the pod and working on its landing gear. He can be seen in a movie presented by NASA as workers create a scale diorama of the surface of the moon, craters and all.

“The space program was important — people don’t realize it was a huge endeavor,” she said.

Pat met her husband in Maryland when she was only 21. Mike had worked with military aviation projects all over the country, but the couple originally thought they would end up moving to California. Instead, one of Mike’s friends invited him to come to Long Island to try an interview with Grumman. Needless to say, he got the job. The couple would live in Port Jefferson for two years before moving to Setauket.

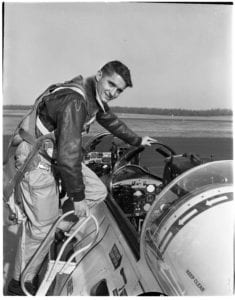

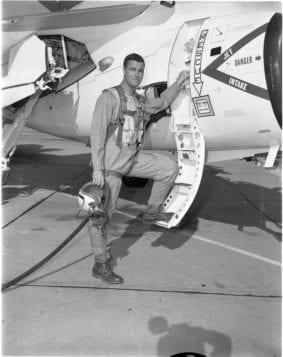

Pat said her husband always had his eye on the sky. Aviation was his dream job, and she remembered how he was “thrilled to pieces” to step into the cockpit of a Grumman F-14 Tomcat.

Mike would be constantly working, so much that during those years of development on the module she would hardly see him at home.

“He was working double shifts and he was going in between Calverton and Bethpage,” she said. “I hardly saw him at all.”

But there were a few perks. Solan and her husband would see many astronauts as Grumman brought them in to test on the simulators. She met several of the early astronauts, but perhaps the most memorable of them was Russell “Rusty” Schweickart, all due to his quick wit and his outgoing personality compared to the stauncher, military-minded fellow astronauts. Schweickart would be pilot on the Apollo 9 mission, the third crewed space mission that would showcase the effectiveness of the lunar module, testing systems that would be critical toward the future moon landing.

She, along with Mike, would also go down to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and there she was allowed to walk in the silo. Standing underneath the massive girders, it was perhaps the most impressive thing she has ever seen in her life.

“It was absolutely mind-boggling — it was very impressive,” she said. “I can still remember that. I was stricken.”

On the day of the landing, July 20, 1969, Pat was hosting a party to watch the dramatic occasion at her home, then in Setauket. It could have barely been a more auspicious day, as she had just given birth to her daughter Rolin July 8.

Eventually, Mike would have multiple strokes through the late 1970s and ’80s, and the stress of it would cause him to retire in 1994. He died a few years later.

“He really felt he was not capable of doing presentations to the government anymore,” she said.

But being so close to the work tied to getting man into space has left an impression on her. Herself being an artist, having sold paintings, both landscapes and impressionistic, along with photography and felt sculptures, the effort of the people who put a human on the moon showed her the extent of human and American achievement.

“It was a time of such cooperation — I think it’s sad we don’t see that now,” she said.

Despite current events, she said she still believes the U.S. can achieve great things, though it will take a concerted effort.

“People have to move outside their own persona,” she added. “People are too wrapped up, everything is centered on oneself instead of a bigger picture, the whole.”

Joseph Marino — Northport

By Donna Deedy

Fifty years ago, on July 20, 1969, man walked on the surface of the moon.

Northport resident Joseph Marino spent 10 years on the Apollo mission as a Grumman systems engineer, involved from the very beginning of the project in 1962 to the last landing on the moon. He still finds the achievement remarkable.

“It was the most exciting program — the peak of my career — no question,” he said. “I couldn’t have been more pleased with the results of such a successful project.”

Marino oversaw the design of the systems for the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), as it was originally known, and managed 300 engineers and also psychologists who were needed to work out the man/machine interface that dictated equipment design, such as visual display systems the crew relied upon during precarious moments of landing and docking.

An error in timing, particularly during landing, he said, could be disastrous.

“Astronauts are the coolest characters capable of handling any situation imaginable,” Marino said. “It’s crucial for the crew to know when you make contact with the surface, so they know when to shut off the engine.”

The team ultimately created an alert system with red flashing lights wired to 3- to 4-foot-long probes positioned on the module’s landing gear.

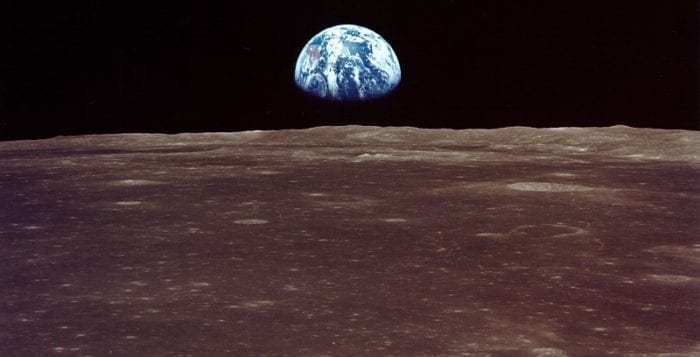

The most dramatic, awe-inspiring moment of all during the Apollo missions, Marino said, was when the astronauts witnessed the Earth rising above the horizon of the moon’s cratered landscape. The event was memorialized in what has become an iconic photo that most people today have seen. Marino cherishes that shot.

NASA’s moon mission has been an endless source of inspiration for mankind. In fact, people can thank the space program for popularizing inventions big and little. Computers, very primitive versions of what are popular today, were first used by NASA. Velcro, Marino said, was also invented during the Apollo program and later became broadly popular.

Looking back, now that 50 years have passed, Marino said it’s disturbing to him that there’s been such a wide gap in time since the last moon landing and today.

He recently spoke to his granddaughter’s high school class and told them, “Not only did man walk on the surface of the moon before you were born, likely it occurred before your parents were born.”

The bond Marino has developed with his aerospace colleagues has lasted a lifetime. Each month, he still meets with a dozen co-workers for lunch at the Old Dock Inn in Kings Park.

For the 50th anniversary, Marino says that he’s been enjoying the special programming on PBS. He recommends its three-part series called “Chasing the Moon.”

Frank Rizzo — Melville

By Rita J. Egan

For Frank Rizzo, his experience of working on the Apollo program while a Grumman employee was more about dollars and cents.

Rizzo, 85, was with the aerospace engineering company for 33 years. While he retired as a vice president, in the years leading up to the moon landing, he was an accounting manager with the Grumman lunar module program. The Melville resident said it was an exciting time at Grumman.

Work, he said, began on the project a few years before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first steps on the moon. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration established a work package budgeting system with Grumman, and Rizzo, who lived in Dix Hills at the time, said he was responsible for giving the team in the Houston space center the monthly estimate to complete the actual expenditures from an external point of view and also determine profit and loss from an internal point of view.

Rizzo and his co-workers traveled to Houston frequently to review the program with NASA to give the current status from the financial, engineering and manufacturing viewpoints, though sometimes the meetings took place on Long Island. The former accounting manager said many times stand-up meetings were held due to the theory that people become too comfortable when they sit, and stand-up meetings enable for more to get done in less time.

Rizzo said he remembers the original contract, signed in the latter part of 1962, to be valued around $415 million at first. He likened the project to building a house, where it evolves over the years. Revisions come along, and just like one might choose to move a door or window, the budget would need to change regularly.

“When they discovered something from an engineering viewpoint, they had to change the manufacturing scope and materials,” he said.

Rizzo said an example of a significant change was when Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger B. Chaffee were killed in a cabin fire during a launch rehearsal test in 1967. The trio would have been the first crew to take part in the first low Earth orbital test. Due to the horrific incident, a change was made to ensure all material within the lunar module was fireproof.

“That was a major change,” he said. “That entitled us to additional funds to put new materials in it. So those things happened quite frequently — a change to the contract.”

When all was said and done, Rizzo said the contract value between NASA and Grumman totaled more than $2 billion.

During the project, Rizzo said many members of the press would come to visit the Grumman office, including Walter Cronkite who anchored “CBS Evening News” at the time.

“Here was a little place on Long Island being responsible for the actual vehicle that landed on the moon,” he said.

Since the moon landing, Rizzo said seeing similar NASA activities like the Space Shuttle program haven’t been as exciting as the Apollo program.

“A lot of people said it was a waste of money, but that money was spent here for jobs, and many of the things that we got out of the research and development, like cellphones or GPS, and so forth, the basic research and development came out of that NASA program back in the ’60s and ’70s,” he said.

Kicking off tonight with a discussion and reception, the Port Jefferson Village Center will present an exhibit titled Grumman on Long Island, A Photographic Tribute featuring photographs and memorabilia from Grumman. The company, which became part of Northrop Grumman in 1994, started in 1929 and was involved in everything from the design of F-14 fighter jets to the lunar excursion module that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the surface of the moon 50 years ago this July.

Kicking off tonight with a discussion and reception, the Port Jefferson Village Center will present an exhibit titled Grumman on Long Island, A Photographic Tribute featuring photographs and memorabilia from Grumman. The company, which became part of Northrop Grumman in 1994, started in 1929 and was involved in everything from the design of F-14 fighter jets to the lunar excursion module that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the surface of the moon 50 years ago this July.