By Elana Glowatz & Rachel Shapiro

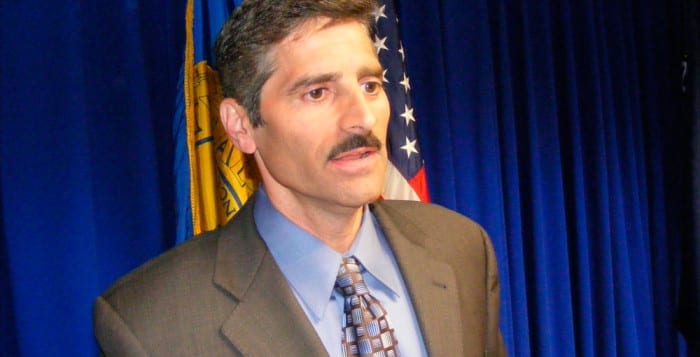

Suffolk County officials, including former County Executive Steve Levy, “intentionally corrupted and undermined” the Ethics Commission and contributed to its disbandment, according to a special grand jury report released April 19.

Testimony in the report by unnamed county officials alleges that County Official E, who worked in the county executive’s office, attempted to influence ethics commissioners’ decisions; tried to use an ethics complaint as leverage against a legislator to influence his vote; and had not received proper authorization to file financial disclosure forms, among other offenses.

Based on previous reporting, this newspaper determined that County Official E is Levy.

Testimony in the report alleges that other county officials colluded with Levy in these actions as well as committed separate offenses. County Official H, the report said, was an Association of Municipal Employees worker who filled out his time sheets and calculated his accruals as a management employee, leading to him receiving more than $14,000 in health benefits he did not earn.

This newspaper, also based on previous reporting, has determined County Official H to be Alfred Lama, the former executive director of the Ethics Commission.

No charges have been filed against the officials, as testimony did not reveal any illegal activity. The grand jury instead made recommendations to the executive and legislative branches — including creating penalties for ethics violations such as improperly influencing the members of an ethics board or commission — and future county ethics bodies, such as enacting procedural guidelines regarding complaints, hearings and decisions.

Levy took issue with the report. It was “based in large part on testimony from political detractors of the county executive,” he said in a statement shortly after it was released Thursday.

He said seeking the commission’s opinion on a potential conflict of interest, as he did in the case of the legislator, “is not an abuse of the Ethics Commission, it’s the very reason you have one,” and that he did not tell Ethics Commission members how to vote on any issue.

The former county executive also took issue with the report saying that while, for a time, he only filed state financial disclosure forms, he was obligated to file county forms, which the report said were more thorough.

Mark Davies, a former executive director of the Temporary State Commission on Local Government Ethics who drafted state ethics law, said in written testimony to the Suffolk County Legislature in September 2010 that “on the whole, the state form is more extensive than the county form.” He argued that because the county form lacked certain categories, such as offices in political parties and organizations and agreements for future employment, it was not in compliance with state law. Legislation has since been introduced to bring the local form into compliance with state law.

Levy also said that state law mandated the county to accept the state form over the county form, something the grand jury report said “remains an open question with advocates on both sides publicly arguing their positions.” Lama advised the former county executive without a ruling from the entire Ethics Commission, saying Levy could file the state form instead of the county form.

The grand jury report also discussed the findings of an audit by the county comptroller. Lama, who was the ethics commission’s executive director from 2004 until it was abolished, was audited last year. According to the document from Comptroller Joe Sawicki’s office, the investigation was to determine whether the director’s hours worked from 2004 to 2011 had been logged correctly, and whether he was given appropriate pay and health benefits according to the hours he had worked.

The grand jury report said Lama, an AME union employee, had filled out his time sheets as if he were a management employee. It also said there was no evidence of fraud on Lama’s part.

Sawicki said in an interview that he began reviewing Lama’s time sheets and found that the director had often worked less than 50 percent of the work week. The audit states, “[Lama] worked 84 percent of the required full-time hours in 2005 and only 49 percent of the required full-time hours in 2010.” The audit states the county attorney did not change the position to part-time so the director would have the flexibility to work full-time if needed.

The comptroller’s audit found that Lama had been overpaid more than $8,000 in wages and had received more than $14,000 in health insurance coverage premiums that he did not reimburse to the county — from periods when he worked less than 50 percent of the work week and therefore, the audit stated, was not entitled to the premiums.

According to the Suffolk County AME contract, part-time employees “must work greater than 50 percent of the established work week to be entitled to benefits.” Those who fall below that mark, the contract says, may purchase health insurance on a pro rata basis.

Lama said in a phone interview Tuesday that he did not know he was a union employee, and filled out his time sheets for the 7.5-hour day of a management employee.

The grand jury report said Lama signed a “new employee orientation” document, acknowledging his “receipt of the collective bargaining agreement for his AME position and his AME enrollment card.” However, Lama said he went to an orientation when he was hired and “they handed me a piece of paper and I signed it. I wasn’t aware that they were going to put me into the union.”

He added that he always tried to be “as truthful as possible” when filling out his logs, and questioned why it took so long for someone to tell him he was filling in his time sheets incorrectly. “Don’t wait until the end of the rainbow and tell me I made a mistake,” he said.