By Daniel Dunaief

For scientists, meetings and conferences aren’t just a chance to catch up on the latest research, gossip and see old friends: they can also provide an intellectual spark that enhances their careers and leads to new collaborations.

Amid the pandemic, almost all of those in-person conferences stopped, including the annual courses and meetings that Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory hosts. The internationally renowned lab has run meetings since 1933, with a few years off between 1943 and 1945 during World War II.

While scientists made progress on everything from basic to translational research, including in laboratories that pivoted towards work on the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, they missed out on the kinds of opportunities that come from in-person interactions.

Assuming COVID infection rates are low enough this fall, CSHL is hoping to restart in-person conferences and courses, with the first conference that will address fifty years of the enzyme reverse transcriptase scheduled for Oct. 20th through the 23rd. That event was originally scheduled for October of 2020.

One of the planned guest speakers for that conference, David Baltimore, who discovered the enzyme that enables RNA to transfer information to DNA and is involved in retroviruses like HIV, won the Nobel Prize.

“I am hoping that there will be significant participation by many eminent scientists, so that is in itself somewhat [of] a ceremonial start,” wrote David Stewart, Executive Director of meetings and courses at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

To attend any of the seven in-person meetings on the calendar before the end of the year, participants need to have vaccinations from either Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson or AstraZeneca.

Attendees will have to complete an online form and bring a vaccination card or certificate. Scientists who don’t provide that information “will not be admitted and will not get a key to their room or be able to attend the event,” Stewart said.

CSHL also plans to maintain the thorough and deep cleaning procedures the lab developed.

Stewart hopes that 75 to 80 percent or more of the talks presented will be live, with a virtual audience that could be larger than the in-person attendance.

“It is important to have a critical mass of presenters and audience in-person, but there’s no real limit on how large the virtual audience could be,” he explained.

Typically, the courses attract participants from over 50 countries. Even this year, especially with travel restrictions for some countries still in place, Stewart expects that the majority of participants will travel from locations within the United States.

The Executive Director explained that CSHL was planning to introduce a carbon offset program for all travel to conferences and courses that the facility reimburses starting in 2020. After evaluating several options, they plan to purchase carbon offsets from Cool Effect and will encourage participants paying their own way to do the same or through a similar program.

The courses, meanwhile, will begin on October 4th, with macromolecular crystallography and programming for biology. CSHL hopes to run six of these courses before the end of the year, including a scientific writing retreat.

“We are looking to 100 percent enrollment for our courses, so likely this year that will largely be domestic,” Stewart explained.

The courses, which normally have 16 participants, may have 12 students, as the lab tries to run these training opportunities safely without masks or social distancing.

From March of 2020 through the end of last year, the lab had planned 25 meetings and 25 courses. As the pandemic spread, the lab pivoted to virtual meetings. “I felt like a car salesman trying to sell virtual conferences,” Stewart recalled. For the most part, the lab was able to keep to its original schedule of conferences, albeit through a virtual format.

In addition to the scheduled meetings, CSHL decided to add meetings to discuss the latest scientific information related to COVID research.

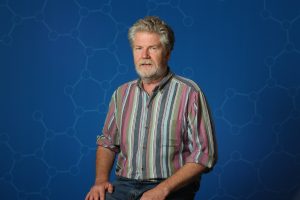

Stewart approached Hung Fan, a retired virologist at the University of California at Irvine, to help put together these COVID exchanges. Those meetings occurred in June, July, August, October, and January. The sixth one recently concluded.

The meetings addressed “everything around the science of the virus,” Stewart said, which included the biology, the origin, the genomics, the immune response, vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics, among other scientific issues.

“There was a lot of excellent work being done around SARS-CoV-2,” Stewart said. “We were trying to identify that early on. It was helpful to have people who knew the field well.”

Fan said he combed through preprints like the CSHL-based bioRxiv and related medRxiv every day for important updates on the disease.

Fan described the scientific focus and effort of the research community as being akin to the Manhattan Project which built the atomic bomb during World War II, where “everybody said, ‘We have a common enemy and we want to apply all our capabilities to combating that.”

While Fan is pleased with the productive and valuable exchanges that occurred amid the virtual conferences, he recognized the benefit of sharing a room and a drink with scientific colleagues.

“A lot of the productive interactions at meetings take place in a social setting, at the bar, over dinner” and in other unstructured gatherings, he said. “People are relaxed and can share their scientific thoughts.”

After presentations, Fan described how researchers discuss the work presented and compare that to their own efforts. It’s easier to talk with people in person “as opposed to making a formalized approach through letters and emails.”