By Beverly C. Tyler

A book titled “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory,” by Anne Farrow, uses a log of three voyages over a period of 20 months in the first half of the 18th century, recorded by a young Connecticut man who went on to captain slave ships and privateers, to tell a much wider and disturbing story.

Farrow’s book connects Dudley Saltonstall, the Connecticut man who kept the log books, to the unknown slaves who were transported from Africa, then to the men in Africa who first enslaved them, to the ships that transported them across the Atlantic, and finally to the men who purchased them to work to death in the Caribbean sugar plantations and in the rice plantations of America’s southern colonies.

Farrow, a former Connecticut newspaper reporter, said the story of African-American people must be told over and over, from the beginning. She said she believes that it has not yet been absorbed into the family of stories told and retold about America and that the story of injustice and suffering still has not made its way into the national narrative.

Unknown to most Americans is the fact that colonial Connecticut had been a major hotbed of British West Indies plantations where slaves were growing and processing sugar in a monoculture that yielded huge profits to England. In addition, Rhode Island men were at the helm of 90 percent of the ships that brought the captives to the American south, an estimated 900 ships.

Farrow noted that over the course of two centuries an estimated three million Africans were carried to islands in the Caribbean to grow sugar.

Farrow’s book, compact enough to be read in just a few days, is an engaging, local and personal history. The story of the Connecticut and Long Island Sound men who took part in the slave trade is disturbingly real.

It brings into focus the way many of our own prosperous and influential Long Island families made their fortunes. It doesn’t change who they were or who we are, but it provides us with a clearer understanding of the pain and suffering caused by their actions.

Farrow emphasizes that we should acknowledge what was done and keep it as a reminder of man’s inhumanity to man and how we are continually striving, often unsuccessfully, to make our lives better for all.

The book is also the story of her mother’s declining memory due to dementia, the memories her mother would never recover, and the log books, the story she did recover.

Farrow wrote, “I couldn’t avoid the contrast between what was happening to my mother’s memory and the historical memory I was studying, which seemed so fractured and incomplete.”

It is again and again evident from Farrow’s research and gripping prose that slavery was not just a southern problem. Slavery served white people in the north and in the south. Farrow notes that the killing uncertainties of life as a captive were linked to the state of bondage not geography.

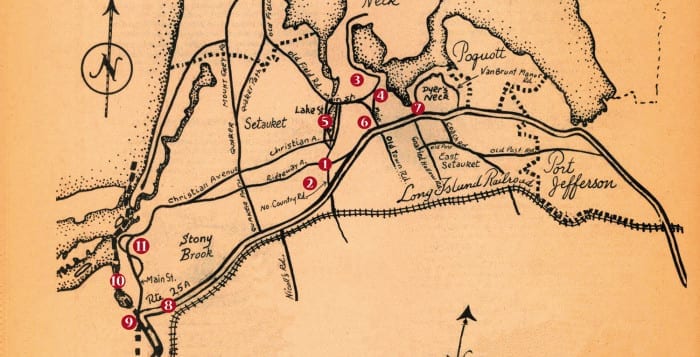

In spite of the federal law prohibiting the importation of slaves from Africa, slaves were still being transported from Africa across the Atlantic until at least the beginning of the American Civil War. The story of one of our own East Setauket slave ships, Wanderer, was detailed in my column two weeks ago. I must apologize that the name of the primary author of that article, William B. Minuse, was omitted from the opening credits.

Beverly Tyler is the Three Village Historical Society historian.