By Daniel Dunaief

This part one of a two part series.

It’s a bit like shaking corn kernels over an open flame. At first, the kernels rustle around in the bag, making noise as they heat up, preparing for the metamorphosis.

That’s what can happen in any of the many laboratories scattered throughout Long Island, as researchers pursue their projects with support, funding and guidance from lab leaders or, in the science vernacular, principal investigators.

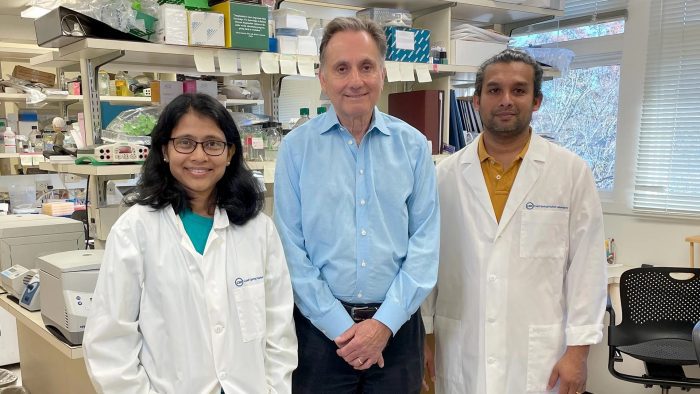

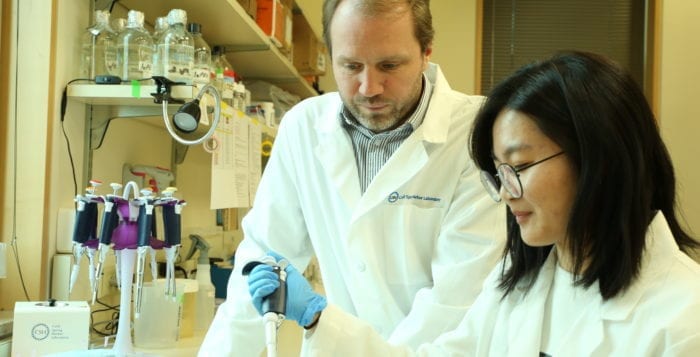

Sometimes, as happened recently at the benches of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Assistant Professor Tobias Janowitz, several projects can pop at around the same time, producing compelling results, helping advance the careers of developing scientists and leading to published papers.

PhD graduate Miriam Ferrer Gonzalez and MD/ PhD student Sam Kleeman recently published separate studies.

In an email, Janowitz suggested the work for these papers is “time consuming and requires a lot of energy.” He called the acceptance of the papers “rewarding.”

In a two-part series, Times Beacon Record News Media will describe the research from each student. This week, the focus is on Ferrer Gonzalez. Check back next week for a profile of the work of Kleeman.

Miriam Ferrer Gonzalez

Miriam Ferrer Gonzalez was stuck. She had two results, but couldn’t seem to figure out how to connect them. First, in a mouse model of the ketogenic diet — heavy on fats, without including carbohydrates —cancer tumors shrunk. That was the good news.

The bad news, which was even more pronounced than the good, was that this diet was not only starving the tumors, but was triggering an earlier onset of cachexia, in which bodies weaken and waste away. The cachexia overpowered the mice, causing them to die sooner than if they had a normal diet.

Ferrer, a student in residence from Spain who was conducting her research at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory while earning her PhD at the University of Cambridge in the UK, thought the two discoveries were paradoxically uncoupled. A lower tumor burden, she reasoned, should have been beneficial.

In presenting and discussing her findings internally to the lab group, Ferrer received the kind of feedback that helped her hone in on the potential explanation.

“Finding out the mechanism by which a ketogenic diet was detrimental for both the body and the cancer was the key to explaining this uncoupling,” Ferrer explained.

The adrenal glands of mice fed a ketogenic diet were not producing the necessary amount of the hormone corticosterone to sustain survival. She validated this broken pathway when she discovered higher levels of corticosterone precursors that didn’t become functional hormones.

To test this hypothesis, she gave mice dexamethasone, which boosted their corticosterone levels. These mice had slower growing tumors and longer lives.

Ferrer recently published her paper in the journal Cell Metabolism.

To date, the literature on the ketogenic diet and cancer has been “confusing,” she said, with studies that show positive and negative effects.

“In our study, we go deeper to explain the mechanism rather than only talking about glucose-dependency of cancer cells and the use of nutritional interventions that deprive the tumor of glucose,” said Ferrer. She believed those factors are contributing to slower tumor growth, but are not solely responsible.

Thus far, there have been case studies with the ketogenic diet shrinking tumors in patients with cancer and, in particular, with glioblastoma, but no one has conducted a conclusive clinical trial on the ketogenic diet.

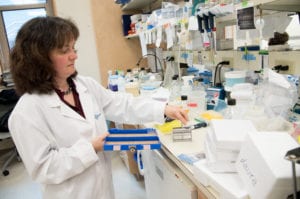

Researchers have reported on the beneficial effects of this diet on epilepsy and other neurological diseases, but cancer results have been inconclusive. For the experiments in Janowitz’s lab, Ferrer and technician Emma Davidson conducted research on mouse models.

Ferrer, who is the first author on the paper, has been working with this system for about four years. Davidson, who graduated from the College of Wooster in Ohio last year and is applying to MD and MD/PhD programs, contributed to this effort for about a year.

Next steps

Now that she earned her PhD, Ferrer is thinking about the next steps in her career and is considering different institutions across the country. Specifically, she’s interested in eating behavior, energy homeostasis, food intake and other metabolic parameters in conditions of stress. She would also like to focus on how hormonal cycles in women affect their eating behavior.

Originally from a small city in Spain called Lleida, which is in the western part of Catalonia, Ferrer appreciated the opportunity to learn through courses and conferences at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Until she leaves the lab in the next few months, Ferrer plans to work with Davidson to prepare her to take over the project for the next year.

The follow up experiments will include pharmacologically inducing ferroptosis of cancer cells in mice fed a ketogenic diet. They hope to demonstrate that early induction of ferroptosis, or a type of programmed cell death, prevents tumor growth and prevents the tumor-induced reprogramming of the rest of the body that causes cachexia.

These experiments will involve working with mice that have smaller and earlier tumors than the ones in the published paper. In addition, they will combine a ketogenic diet, dexamethasone and a ferroptosis inducing drug, which they didn’t use in the earlier experiments.

Janowitz has partnered with Ferrer since 2018, when she conducted her master’s research at the University of Cambridge. As the most senior person in Janowitz’s lab, Ferrer has helped train many of the people who have worked in his lab. She has found mentoring rewarding and appreciates the opportunity to invest in people like Davidson.

Ferrer, who is planning a wedding in Spain in September, is a fitness and wellness fan and has taken nutrition courses. She does weight lifting and running.

Ferrer’s parents don’t have advanced educational degrees and they supported their three children in their efforts to earn their degrees.

“I wanted to be the best student for my parents,” said Ferrer, who is the middle child. She “wanted to make my parents proud.

The hand off

For her part, Davidson is looking forward to addressing ways to implement further treatment methods with a ketogenic diet and supplemental glucocorticoids to shrink tumors and prevent cachexia.

Davidson appreciated how dependable Ferrer was during her time in the lab. Just as importantly, she admired how Ferrer provided a “safe area to fail.”

At one point, Davidson had taken all the cells she was planning to use to inject in mice. Ferrer reminded her to keep some in stock.

“Open lines of communication have been very beneficial to avoid more consequential failures,” Davidson said, ”as this mistake would have been.”

Davidson developed an interest in science when she took a high school class called Principles in Biological Science and Human Body Systems. When she was learning about the cardiovascular system, her grandfather had a heart attack. In speaking with doctors, Davidson acted as a family translator, using the language she had studied to understand what doctors were describing.

Like Ferrer, Davidson lives an active life. Davidson is preparing for the Jones Beach Ironman Triathlon in September, in which she’ll swim 1.2 miles, bike 56 miles and run a half marathon. She plans to train a few hours during weekdays and even more on weekends for a competition she expects could take about six hours to complete.

Davidson started training for these events with her father Mark, an independent technology and operations consultant and owner of Exoro Consulting Group.

Longer term, Davidson is interested in medicine and research. After she completes her education, she will try to balance between research and clinical work.