By John L. Turner

On my way to redeem some bottles, involving some brands of craft beer that were thoroughly enjoyable, I did a double take passing by what I thought was a small bit of wind-blown garbage, moved by a gentle breeze, along the curb in a supermarket parking lot. Something about its movement caught my eye though and upon a closer look this was no multi-colored piece of trash but rather was something alive, fluttering weakly against the curb. Bending down to take a closer look I suddenly realized I was staring, improbably, at a male Polyphemus Moth (I could tell it was a male by its quite feathery antennae).

I picked the moth up and moved it out of harm’s way, placing it under a nearby row of shrubs, realizing all I did was buy it a little more time free from a certain death by a car tire or pedestrian foot. Having no mouth with which it can feed (all of its energy is carried over from the caterpillar stage) a trait it shares with related species, its life as an adult is short-lived.

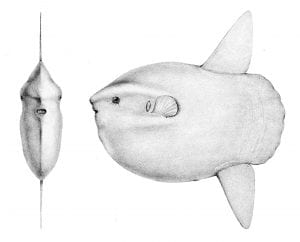

The Polyphemus Moth is one of more than a dozen species of Giant Silk Moths found on Long Island. This family contains some of the largest moths in the world and they range from attractive to beautiful to spectacular.

Take the Polyphemus Moth as an example. Tan colored with bands of peach on the forewings and black on the hind wings, the moth has four eye spots with the two on the hind wings being especially prominent. The center of the eyespots appears cellophane-like and is translucent. The central eyespot gives rise to the species name as it is reminiscent of the eye of the cyclops of Greek mythology with the same common name as the moth.

The eye spots also play a role in the family name — Saturnidae, as some eye spots have concentric rings like those of the planet Saturn. And as moths go this creature has a huge wingspan, being as much as five inches from the tip of one forewing to the other. Its caterpillars feed on oak trees.

The richly-colored brown, olive, and orange Cecropia moth, with its bright orange body, is slightly larger than the Polyphemus and its eyespots are more in the shape of a comma. They have a purple patch of the tip of each forewing that reminds me of the ghosts in Pac-Man, the popular video game. Cecropia prefer cherry trees as a food plant.

The most tropical looking member of the family is undoubtedly the lime green-colored Luna Moth, a feeder of walnut leaves. The hindwings of the species, also possessing two eye spots, are longer than other Giant Silk Moth members and have a distinctive twist to the two “tails.” The spots on the fore or front wings are smaller, oval and are connected by a line to the purplish/maroon-colored line that runs along the front of the forewing. It is a showstopper!

A non-native Giant Silk moth has been introduced to Long Island — the Ailanthus Silk Moth also known as the Cynthia Moth. It can be seen in areas of the island where Ailanthus trees commonly grow such as Brooklyn and Queens.

Two beautiful, closely related silk moths are the Tulip-tree Silk Moth and the Promethea Moth. The latter species is sexually dimorphic, meaning the male and female look different as they are of “different morphs or forms.” The female is a rich blend of browns with an orange body while the male is a deep charcoal grey with olive to tan borders on both wings. As the name suggests, the former species as a caterpillar feeds on the leaves of the Tulip Tree, a spectacular columnar tree that grows in richer soils along Long Island’s north shore.

Related to these other Giant Silk Moths is a smaller inhabitant found in the Long Island Pine Barrens — the Eastern Buck Moth. And unlike other giant silk moths, and moths in general, the buck moth is strictly diurnal, flying from late morning through mid-afternoon on days in late September through mid-October. Why the radical difference in lifestyle compared to typical night flying moths? It has to do with living in a fire-prone environment. Unlike other members of the family, buck moths don’t pupate by forming a cocoon that hangs from a branch because it would run the real risk of being destroyed by fire. Rather, the buck moth pupates in an earthen cell underground, out of harm’s way, waiting until the threat of the fire season lessens. This means a shift in emergence to the fall, and since it can get cold at night, buck moths have shifted their active period to the warmer daytime.

In the same subfamily as the buck moth is the beautiful Io Moth. This species too is dimorphic with the female being darker than the male’s bright yellow coloration. Both sexes have large eyespots on their hindwings which are revealed when the forewings are thrown forward by a disturbed moth; suddenly the here-to-fore innocuous insect appears to be the face of a mammal which may deter predation or allow the momentarily confused predator to give enough time for the Io moth to escape.

In yet another subfamily are the remarkable Pine Devil moth, Royal Walnut Moth (which as a caterpillar is the famous hickory horned devil!), Imperial Moth, three species of oak webworms common in the Pine Barrens, and the Rosy Maple Moth, the color of raspberry and lemon sherbet.

Unfortunately, all of these species have become less common on Long Island with some perhaps on the verge of extirpation (local extinction), done in by a loss of habitat and the widespread use of pesticides. Their rarity, paired with exceptional beauty, makes seeing a member of the Giant Silk moth family a special visual treat. Good luck!

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.