Exercise and sleep are crucial to clearing the clutter

By David Dunaief, M.D.

Considering the importance of our brain to our functioning, it’s startling how little we know about it.

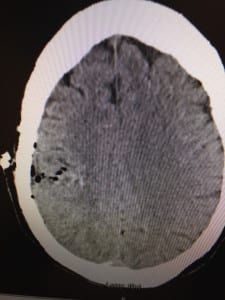

We do know that certain drugs, head injuries and lifestyle choices negatively impact the brain. There are also numerous disorders and diseases that affect the brain, including neurological (dementia, Parkinson’s, stroke), infectious (meningitis), rheumatologic (lupus and rheumatoid arthritis), cancer (primary and secondary tumors), psychiatric mood disorders (depression, anxiety, schizophrenia), diabetes and heart disease.

Although these diseases vary widely, they generally have three signs and symptoms in common: they either cause altered mental status, physical weakness or change in mood — or a combination of these.

Probably our greatest fear regarding the brain is a loss of cognition. Fortunately, there are several studies that show we may be able to prevent cognitive decline by altering modifiable risk factors. They involve rather simple lifestyle changes: sleep, exercise and possibly omega-3s.

Let’s look at the evidence.

Clutter slows us down as we age

The lack of control over our mental capabilities as we age frightens many of us. Those who are in their 20s seem to be much sharper and quicker. But are they really?

In a study, German researchers found that educated older people tend to have a larger mental database of words and phrases to pull from since they have been around longer and have more experience (1). When this is factored into the equation, the difference in terms of age-related cognitive decline becomes negligible.

This study involved data mining and creating simulations. It showed that mental slowing may be at least partially related to the amount of clutter or data that we accumulate over the years. The more you know, the harder it becomes to come up with a simple answer to something. We may need a reboot just like a computer. This may be possible through sleep, exercise and omega-3s.

Get enough sleep

Why should we dedicate 33 percent of our lives to sleep? There are several good reasons. One involves clearing the mind, and another involves improving our economic outlook.

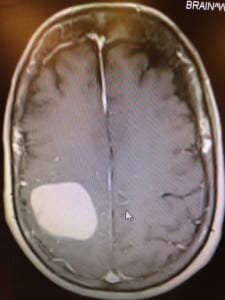

For the former, a study done in mice shows that sleep may help the brain remove waste, such as those all-too-dangerous beta-amyloid plaques (2). When we have excessive plaque buildup in the brain, it may be a sign of Alzheimer’s. When mice were sleeping, the interstitial space (the space between brain gyri, or structures) increased by as much as 60 percent.

This allowed the lymphatic system, with its cerebrospinal fluid, to clear out plaques, toxins and other waste that had developed during waking hours. With the enlargement of the interstitial space during sleep, waste removal was quicker and more thorough, because cerebrospinal fluid could reach much farther into the spaces. A similar effect was seen when the mice were anesthetized.

In another study, done in Australia, results showed that sleep deprivation may have been responsible for an almost one percent decline in gross domestic product for the country (3). The reason? People are not as productive at work when they don’t get enough sleep. They tend to be more irritable, and concentration may be affected. We may be able to turn on and off sleepiness on short-term basis, depending on the environment, but we can’t do this continually.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, four percent of Americans reported having fallen asleep in the past 30 days behind the wheel of a car (4). And “drowsy driving” led to 83,000 crashes in a four-year period ending in 2009, according to The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Prioritize exercise

How can I exercise, when I can’t even get enough sleep? Well there is a study that just may inspire you.

In the study, which involved rats, those that were not allowed to exercise were found to have rewired neurons in the area of their medulla, the part of the brain involved in breathing and other involuntary activities. There was more sympathetic (excitatory) stimulus that could lead to increased risk of heart disease (5). In rats allowed to exercise regularly, there was no unusual wiring, and sympathetic stimuli remained constant. This may imply that being sedentary has negative effects on both the brain and the heart.

This is intriguing since we used to think that our brain’s plasticity, or ability to grow and connect neurons, was finite and stopped after adolescence. This study’s implication is that a lack of exercise causes unwanted new connections. Human studies should be done to confirm this impact.

Consume omega-3 fatty acids

In the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study, results showed that those postmenopausal women who were in the highest quartile of omega-3 fatty acids had significantly greater brain volume and hippocampal volume than those in the lowest quartile (6). The hippocampus is involved in memory and cognitive function.

Specifically, the researchers looked at the levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in red blood cell membranes. The source of the omega-3 fatty acids could either have been from fish or supplementation.

It’s never too late to improve brain function. Although we have a lot to learn about the functioning of the brain, we know that there are relatively simple ways we can positively influence it.

References:

(1) Top Cogn Sci. 2014 Jan.;6:5-42. (2) Science. 2013 Oct. 18;342:373-377. (3) Sleep. 2006 Mar.;29:299-305. (4) cdc.gov. (5) J Comp Neurol. 2014 Feb. 15;522:499-513. (6) Neurology. 2014;82:435-442.

Dr. David Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management. For further information, visit www.medicalcompassmd.com.