Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

What happens after “The End?” After the villain is vanquished and order is restored? When the heroes go on to the rest of their lives? The gifted, prolific fantasy author Sarah Beth Durst explores this concept in her enthralling new adult novel, The Bone Maker (published by Harper Voyager).

Twenty-five years before, five extraordinary heroes saved Vos from the destructive forces of the evil Eklor, “a man who dealt death the way a card player dealt cards.” While Eklor was slain and his animated minions destroyed, one of the quintet died in battle. With this, the remaining four went their separate ways.

The book opens a quarter of a century after the war, with a crime of body snatching. Kreya, the leader of the good forces, has been on a mission to resurrect her husband, Jentt, who was the fallen warrior. Kreya has used Eklor’s notebooks to bring him back, justifying the use of her enemy’s research. “Knowledge itself isn’t evil. It’s how you use it.” But the decision haunts her.

In this society, the bone makers and their ilk are permitted to use animal bones for their magic. Kreya’s dilapidated tower home is populated by a host of benign creatures. But utilizing human bones is forbidden, adding to Kreya’s moral dilemma. Until now, she had been collecting bones from unlit pyres. Now, she wants to revisit the field of battle to acquire what she needs once and for all.

All of this is part of the exceptional world-building for which Durst is known and so adept. She creates a detailed, accessible universe and accompanying mythology that are always true onto themselves. At the center are the people who deal in these enchantments:

As far as the guild was concerned, there were only three types of bone workers: bone readers, who used animal bones to reveal the future, understand the present, and glimpse the past; bone wizards, who created talismans out of animal bones that imbued their users with speed, stealth, and other attributes; and bone makers, like Kreya, who used animal bones to animate the inanimate. Ships, weaving machines, cable cars … all the advances of the past few centuries had been fueled by bone makers.

In addition to the human bones, Kreya must offer part of her own life force to bring Jentt back. The resurrection spell is one of inverse power: Every day Jentt lives again, she will have one day fewer. She has revived him for short periods, but the suspense in the first part of the book builds to his complete restoration.

When she decides that she must visit his death site to acquire the bones from Vos’s fallen soldiers, she recruits Zera, the bone wizard from her team, who now lives in lavish and hedonistic excess. Zera, a master of talisman creation seems shallow and petty, having parlayed her victory into extraordinary wealth and position. She is engagingly sly, quick with a quip, and outwardly narcissistic. “I require pie before I desecrate a mass grave.” Gradually, her depths are revealed, but she never loses her wicked charm and turn of phrase.

Kreya and Zera venture to the site, returning with the bones and a suspicion that Eklor either never died or has been brought back. Kreya fully restores Jentt to life. Then, along with Zera, gather the two remaining members of their troupe: Marso, the bone reader, whose skill “far exceeded the skills of other bone readers,” and Stran, “a warrior with the experience in using bone talismans to enhance his already prodigious strength.” However, Marso, plagued by doubt and perhaps a touch of madness, sleeps naked on the streets of the least savory of Vos’s cities. Stran has entered a life of contented domesticity, living happily with his wife and three children on a farm. Kreya must reunite this disparate group to bring order once again.

Kreya and Zera venture to the site, returning with the bones and a suspicion that Eklor either never died or has been brought back. Kreya fully restores Jentt to life. Then, along with Zera, gather the two remaining members of their troupe: Marso, the bone reader, whose skill “far exceeded the skills of other bone readers,” and Stran, “a warrior with the experience in using bone talismans to enhance his already prodigious strength.” However, Marso, plagued by doubt and perhaps a touch of madness, sleeps naked on the streets of the least savory of Vos’s cities. Stran has entered a life of contented domesticity, living happily with his wife and three children on a farm. Kreya must reunite this disparate group to bring order once again.

Paramount is that then, and now, Kreya is their leader. As Zera states: “Ahh, but what not everyone knows is this: the legend says that the guild master tasked five, but he did not. He tasked only one. Kreya. She chose the rest of us. All that befell us is her fault. All the glory, and all the pain.” Kreya carried this responsibility during the first war and will do so again.

The Bone Maker refreshingly lacks preciousness. The characters struggle with darkness, inner demons, and attitude. The core team shares common bonds: fear and love, blended with resentments and guilt. The reluctance to take on this new adventure comes from a place of maturity. But once called, they embrace their fates and understand the need — and risk — of sacrifice for the greater good. But even then, they question their actions.

There is no generic nobility. Fallible human beings inhabit this world of fantasy. Kreya is a portrait of loneliness, living like a hermit with her creations, who she calls “my little ones,” monomaniacally focused on raising her husband. Jentt, alive, reflects that “Every time I wake, all I remember is life.” He has lost all the time in between. Stran yearns to return to his fulfilling family life. And Marso, the most fragile and tormented, desires nothing more than peace of mind.

Even with exploring ethical issues, there are plenty of thrills with a host of unusual and dangerous monsters, including venom-laced stonefish and croco-raptors who hunt in deadly packs. There are rousing battles and daring escapes. Eklor’s formally dormant army of the reanimated is poised for invasion. The guild-led government struggles with shadows of self-interest that tip towards corruption. The citizens of Vos do not want to accept the possibility of another war: “There aren’t many who will believe the dangers of the past have anything to do with them and their lives … they want to believe it’s over.” The plot twists and turns, building to a revelation midway through the book, shifting the story’s entire course to a gripping confrontation and satisfying denouement.

Sometimes labeling a book fantasy can be reductive — that it is “good for that genre.” But whether it is confronting issues of sacrifice, delving into a highly original and unique world of magic, or reveling in the banter of old friends facing new quest, The Bone Maker is a rich and complex tapestry — and a great novel on any terms.

———————————————–

Award-winning author Sarah Beth Durst lives in Stony Brook with her husband, her children, and her ill-mannered cat. The Bone Maker is her 22nd novel and is available at Book Revue in Huntington, Barnes & Noble and on Amazon. For more information, visit sarahbethdurst.com.

I always really enjoyed writing as a child — I loved writing stories and poetry. I went to Emerson College in Boston, where I studied writing and acting, but I mostly focused on screenwriting for TV and movies. Emerson has a Los Angeles program, so I was able to move out to California right after I graduated.

I always really enjoyed writing as a child — I loved writing stories and poetry. I went to Emerson College in Boston, where I studied writing and acting, but I mostly focused on screenwriting for TV and movies. Emerson has a Los Angeles program, so I was able to move out to California right after I graduated.

Who illustrated this book? How did you connect?

Who illustrated this book? How did you connect? Major: Presidential Pup is available at Book Revue in Huntington and online retailers including Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To keep up with Jamie and Erica, their book and animals in need, visit http://linktr.ee/MajorPresidentialPup.

Major: Presidential Pup is available at Book Revue in Huntington and online retailers including Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To keep up with Jamie and Erica, their book and animals in need, visit http://linktr.ee/MajorPresidentialPup.

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

But it’s live oak leaves, Tallamy explains, where the value of oaks come into full focus. More than 500 species of butterflies and moths feed on oak leaves, including many geometrid caterpillars (or inchworms as we learned in our childhoods). Many hundred more other insect species eat oak leaves (or tap into the sap of oaks too), including leafhoppers, treehoppers, and cicadas, among others. These leaf-eating species, in turn, sustain many dozens of songbird species we love to watch — warblers, orioles, thrushes, wrens, chickadees, grosbeaks and more.

But it’s live oak leaves, Tallamy explains, where the value of oaks come into full focus. More than 500 species of butterflies and moths feed on oak leaves, including many geometrid caterpillars (or inchworms as we learned in our childhoods). Many hundred more other insect species eat oak leaves (or tap into the sap of oaks too), including leafhoppers, treehoppers, and cicadas, among others. These leaf-eating species, in turn, sustain many dozens of songbird species we love to watch — warblers, orioles, thrushes, wrens, chickadees, grosbeaks and more.

Where do you get your inspiration?

Where do you get your inspiration?

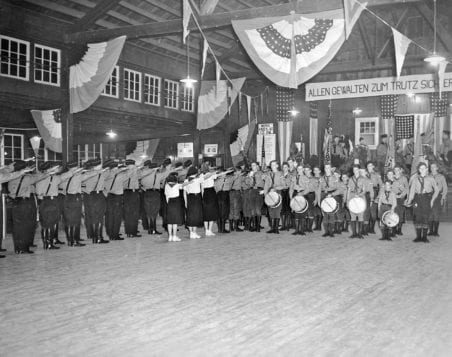

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

Troy’s presence has always been a negative force, and incarceration has made him both bitter and dangerous. Now, he has concocted a murder and kidnapping scheme based on a chance encounter at a service station. Once set in motion, he recruits Mac, a former prison mate, to facilitate the latter part of the crime. Troy forces Lorraine into taking part:

Troy’s presence has always been a negative force, and incarceration has made him both bitter and dangerous. Now, he has concocted a murder and kidnapping scheme based on a chance encounter at a service station. Once set in motion, he recruits Mac, a former prison mate, to facilitate the latter part of the crime. Troy forces Lorraine into taking part: