By John L. Turner

As you begin to read this article please pause for a moment and take stock of your immediate surroundings. What do you feel? Your fingertips feel the largely smooth texture of the surface of the newspaper (perhaps using Meissner corpuscles as I have since learned) and your legs and back feel the chair you’re sitting in. What do you see? Obvious is the fine print of this article and other articles and different shades of color contained in this edition. Lift your gaze to look around a palette of several dozen colors. As for smell? Maybe the aroma of your morning coffee or tea accompanying this reading experience.

Maybe your dog is curled up nearby. While you’d have no reason at this moment to think about it, the worlds you and your dog are currently experiencing are very different. Our entire set of sensory skills — which allows us to perceive and react to the world, varies markedly from a dog’s. We see color while dogs experience a more limited palette. We can detect many scents and odors but is far surpassed by the capability of dogs.

Some research papers indicate their ability to detect smells — “their sense to detect scents” — is 100,000 times more sensitive than ours. And as far as hearing goes, your furry pet far surpasses your ability in what it can hear, especially noises at higher ranges (remember a dog whistle which, when blown, cannot be heard by the person blowing it but is definitely heard by the dog?)

Now, let’s expand this idea outward to capture, say, some animal groups that might inhabit your backyard, such as birds, bats and insects. These groups perceive a very different world than we do. It is well known that some bird and insect species, for example, perceive ultraviolet or UV light, which humans, with rare exceptions, cannot (UV is the light spectrum below a wavelength of 380 nanometers). And a UV illuminated world for them is very different than the world illuminated for us. Certain floral patterns which we can’t see stand out as runways on flower petals for UV capable insects. Birds that have, to our eye, plumage that looks drab, actually have feather coats that radiate under UV light.

As for bats, their famous ability to echolocate — emitting high pitch sounds (too high for us to hear) to locate prey with a high degree of accuracy — is a sense and capability so far outside the realm of human experience as to seem “other worldly.” Several bird species also are capable of echolocation. In the Western Hemisphere that includes the oilbirds of northern South America.

Numerous marine mammal species also are known to echolocate — dolphins, as but one example. And unlike bats whose echolocation skills enable them to “only” detect the outer contours of their prey, dolphins can “see” inside their targets to perceive their organs and skeleton.

Another hard to grasp sense of birds is their ability to detect and utilize the Earth’s magnetic fields which they use to migrate effectively. Researchers aren’t fully sure of the mechanism allowing them to achieve this, but it appears to involve proteins in a bird’s retina.

And I do mean hard to grasp — I’ve read, several times, the same explanatory article in Scientific American on the details of the current hypothesis regarding magnetic field perception in birds and how it aids their migration and I don’t fully understand what’s going on — involving stuff like cytochrome proteins in a bird’s retina, a blue photon hitting the cytochrome causing an electron to jump from an amino acid to a dinucleotide molecule which create a certain spinning of electrons that are, in turn, influenced by the Earth’s magnetic fields which the bird is able to utilize in determining direction. And I’ve left off the last most complicated steps…call me stupid but amazed!

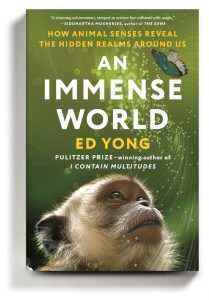

Many other species, such as sea turtles and spiny lobsters, but not us humans, also are known to navigate by using the planet’s magnetic fields but the mechanisms they employ are less well understood. These “other worldly” abilities, and so many more which are so different from ours, are richly revealed in a wonderful, recently published book, An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, by Ed Yong. As the subtitle suggests, Yong takes the reader through dozens of examples of how animals perceive the world in a very different way than we do, using senses we either don’t have or that are far more sensitive or acute. The book is 355 pages of profound discovery and a most worthwhile read.

As an example of the first are animals that can hear or transmit infrasound (below 20Hz), like whales and elephants. Humans can hear sounds as low as about 20 Hz, sounds lower than that are imperceptible to us unless extremely loud, so infrasound is outside our normal perceptive world. Not so with elephants who regularly communicate with infrasound, often involving elephant herds separated by impressive distances such as several miles.

Whales, using the medium of water, easily make sounds that easily exceed this distance, with the blue whale, the largest animal on the planet, generating sounds that can carry many hundreds, if not thousands of miles, in the ocean. When first suggested the idea was thought implausible even ridiculed; it is now widely accepted.

Photo by Urzula Soltys

Or how about being able to feel the warmth of another person’s body that is not close to you but rather is several feet away?

Well, you’ve entered the realm of rattlesnakes which can detect the infrared radiation given off by a mouse from several feet away. And their ability to strike prey just by heat detection is so accurate that blindfolded rattlesnakes can successfully hunt.

As for senses more acute than ours we turn to the hearing of a barn owl. In well-known (and well designed) experiments, barn owls were capable of routinely seizing prey in complete and utter darkness and they have a special feature we lack. Their ear openings are asymmetrically placed, positioned at slightly different heights on the side of the head. So not only can they accurately determine if a sound is coming from their left or right, in the vertical plane (something we do well), they can also tell where the maker of the sound is in the horizontal plane, since if the sound is coming from below, sound waves will reach the lower ear milliseconds before they reach the higher ear, the bird’s brain can process this information and pinpoint its prey.

And then there’s electricity generation. Electricity runs through the human body and is vital to human life. Elements like sodium, magnesium, calcium, and potassium, which we ingest through food and supplements, have electrical charge and enable us to perform basic tasks like nerve generation and transmission and the creation of a heartbeat through muscular contraction. It is reported that the energy output of a resting human adult is equivalent to powering a 100 watt light bulb.

Some animals take electricity, though, to a new level. The best example involves electric eels. By discharging ions within electrocytes, which are specialized cells in specialized organs, the world champion eel has the ability to generate 860 volts of electricity — that’s nearly eight times the strength of the electricity available from your home’s wall outlet and is enough to debilitate and perhaps kill you. While we have little to worry about, not so for the fish and other aquatic animals that share the eel’s domain.

As Yong’s impressively detailed book repeatedly illustrates, the animals that share our planet display a mind-bogglingly rich suite of survival skills for which one article cannot begin to do justice. Let me prove it by one tiny slice of life — a single shorebird species — the Red Knot, a medium sized bird with a robin red colored breast and a spangled pattern of gold, buff, tan, and black on its back. Overwintering in the southern part of South America, flocks of Red Knots move north on the continent in April, launching in mid-May from the beaches of northern Brazil, driven by invisible impulses which we cannot understand, flying unerringly north toward the East Coast of the United States.

Shaming human triathletes by their efforts, they will fly nonstop for several days as they traverse the waters of the western Atlantic, using the Earth’s magnetic fields, perhaps also using the Sun’s polarized light, propelled by breathing in a way so much more efficient than the human respiratory system. Their heart will have beaten perhaps a million beats and their wings flapped several hundred thousand times during this leg.

They land, perhaps along Long Island’s South Shore or southern New Jersey, and begin to feed voraciously, sustained by tiny packets of protein in the form of horseshoe crab eggs — the perfect snack food. They feed so effectively that in a week to ten days they can add 50% more weight onto the weight they had upon arrival; in some cases they may double their weight in the form of subcutaneous fat.

Gaining enough stored energy they head further north for the last leg of their improbable flight, landing in the High Arctic, perhaps guided by those magnetic fields to the same hummock of dwarf tundra plants where, the year before, they established a breeding territory. They have finished their almost impossible to comprehend 9,000 mile long journey. Just one remarkable story illustrating the unique senses and abilities of species, in a global tapestry of species’ stories that collectively form the planet’s book of life.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.