Stony Brook’s Lorna Role finds way to maximize, minimize memories

Not all memories are created equal. Some moments, like the time we first hold our child tower in the memory landscape over the moments we clip our toenails.

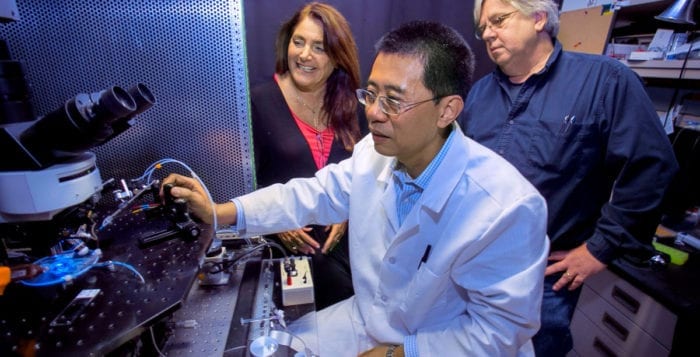

Focused on how we hold onto some of these more important memories, Lorna Role, SUNY distinguished professor and chair of the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior who is also a professor at the Neurosciences Institute at Stony Brook Medicine, used an animal model to test the way a neurotransmitter she’s studied for years, called acetylcholine, might affect memories of a recent, fear-inducing event.

Collaborating with several other scientists, including her husband David Talmage, a professor of pharmacological sciences at Stony Brook University, Role found that stimulating the axons of nerves in the amygdala region of the brain to release acetylcholine during a traumatic event affected the mouse’s behavior for a longer period of time.

On the other hand, reducing acetylcholine in that region during a traumatic event reduced the response. They recently published their work in the journal Neuron.

This research may have applications for conditions such as post traumatic stress disorder. In PTSD, memories of a traumatic event may be significant and painful enough to reduce the quality of life.

To be sure, Role recognizes that there’s a long way to go between what she’s discovered and any potential human therapy. “There are a lot of steps between the basic science set of observations and the applications,” she said. “I don’t have an answer for how it will be done.”

Still, she hopes this type of information could lead to an approach to treating PTSD with nonpharmacological therapies. It also might provide a better target for drug therapies. The results are also consistent with prior work suggesting that cigarette smoking can worsen PTSD. Nicotine is a drug form of acetylcholine.

Role targeted the release of acetylcholine by the cholinergic neurons. Along with Talmage and several other collaborators, Role used the relatively new molecular biology technique of optogenetics. With light, they can activate a select class of neurons without affecting other neurons nearby.

The group went to the axons, which extend far from the cell body, and activated them. “We wanted to go into a particular region associated with a kind of memory and activate the cholinergic terminals,” said Role. They were only releasing acetylcholine in the amygdala.

The group played a tone at the same time the mouse had an unpleasant experience. If the animal had a higher level of acetylcholine for a brief time during that experience, the mouse continued to react in fear in response to the tone even when the sound didn’t occur at the same time as something unpleasant.

“It made the memory essentially indelible. It was much harder to eradicate the memory,” Role said.

When the animal’s acetylcholine levels were lower during the combination of a negative event and the tone, the animal didn’t exhibit fear in response to the sound. “We didn’t expect we could block the recollection of this pairing” of the tone and the unpleasant experience, she said.

One of the next experiments will involve exploring how to decrease the effect of these traumatic experiences after they’ve already occurred.

Talmage, who has a shared lab with Role, said the idea for this set of experiments originated during a meeting in Chicago. The concept was a compelling idea, but “everybody has ideas. It’s what you do with having a crazy idea” that matters. He credits Role with “putting together the team that’s willing to take a risk” to do work that may not pan out as they had hoped. He suggested she spearheaded the research “exceedingly well.”

Role’s broader research interest is in slowing down or reversing memory loss. She is aware of the difficulties families endure when a member has a cognitive decline where that person can’t recognize a loved one.

“It is my hope that not only will we be able to use some of these techniques to strengthen memories that have been diminished, but also to strengthen positive emotionally salient memories,” she said.

Role can envision increasing acetylcholine in these key areas that are important for memory recollection. Cognitive declines can affect the quality of life for people with diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Memories that are critical to Role include moments with her daughters, Lindsay Standeven, who is a psychiatrist and resident at Johns Hopkins, and Masha Role, who is receiving her training as a clinical psychologist.

Role and Talmage, whose descendants include the founding families in Southampton and Bridgehampton and members of the Setauket spy ring during the American Revolution, live in Port Jefferson.

To continue with her research and serve as the chairman of her department, Role wakes up at 4 in the morning and is most productive between 4 a.m. and 9 a.m. She recognizes that collaborating with her doesn’t involve producing numerous papers with incremental results. She’s looking for a broad understanding of what she has discovered before publishing the results and said she discusses the results all the time, because the more feedback she can get, the better.

“Everything I’ve published has been a labor of love over a long time course,” Role said. Her collaborators recognize her need to put all the pieces together before publishing. “I’ve been at this neuroscience research for more than 35 years. I prefer to work to publish as complete a story as possible.”