Obituary: Longtime Rocky Point resident, Plainview teacher remembered

By Christine Zammarco

It started with a hoarse voice that seemed like part of a lingering cold that wouldn’t go away. Then one morning, Peter Sammarco, then 48-years-old, was shaving when he coughed up blood and right away knew something was wrong. After meeting with the doctors, Sammarco was diagnosed; it was throat cancer. Yet, rather than being concerned about what lay ahead, the Plainview history teacher, Rocky Point resident, father and husband met the challenge head on.

“I was pretty hopeful,” he recalled at the age of 81, and speaking by projecting air through his diaphragm.

He was more upset about retiring from his job than he was about losing his voice or even the risk of dying, but Sammarco is from tough stock and from a generation which knew how to work hard and how to fight. He was born in 1930 during the Great Depression. He remembers the absence of his older brothers away serving in the military as he grew up. His Father, Petero, was a tailor and able to trade making suits in exchange for doctor and dentist visits or other services for the family.

As a boy, Sammarco would go to the tailor shop during his lunch breaks in grammar school and enjoyed conversations with two part time Jewish men who worked there — one of whom would become his mentor. The worker would give him history lessons and talk about Hitler and what life was like in Germany, where he immigrated from.

Between the knowledge Sammarco picked up from the workers and the letters he received from his brothers stationed overseas in different parts of the world, he was always learning about current events going on in the world. His teacher would often ask the young man, “how’d you know that?” The teacher even asked him to report current events to the class.

When his brother, Bob, whom Sammarco hadn’t seen in five years, came back from serving in the military, one of the first things he did was grab his younger brother by his collar and take him to St. Ann’s Academy school to enroll. It was an all-boys private school with a cost of $12 a month, which was a lot of money back then, but Bob and his father paid for it. Sammarco was always an above average student with good grades across the board. He graduated in 1948 and planned to go into the military, but again Bob had other plans for him, and took him to Queens College to enroll. He was only the second person in the whole neighborhood to go to college.

“I graduated Sunday, and the Monday after I graduated [the next day] I was sworn into the military,” said Sammarco.

He was in charge of communications in Korea for 17 months. The highlight of his time in Korea was helping the local orphaned children who had no food, clothes, or even underwear. He used his leadership to get the troops stationed there to build an orphanage. He went from tent to tent collecting money. Three days later, a truckload of clothes arrived.

“That was one of the best times of my life because they knew I was responsible for it,” said Sammarco.

The children were amazed by how fast the buildings went up, and Sammarco felt good to leave something of himself behind.

“I came home from Korea in 1954 on military discharge and I said, what am I going to do now?” Sammarco recalled.

Bob guided him and told him about a job at an insurance company. He did very well financially, but working sales wasn’t for him.

“I loved teaching. I always loved teaching,” said Sammarco.

He went back to college at Long Island University’s Brooklyn Campus. He was only there a week when he was called to the office.

“I asked, ‘was there a problem with my check?’ And they said, ‘no’ and offered me a job teaching,” Sammarco recalled. “I said, “but I’ve only been going to school here a week.” The new job was at an all-girls school, namely William Maxwell Commercial High School in Brooklyn.

He went in for the interview not knowing much about the position. Amazingly, they hired him on the spot.

“They didn’t ask me any questions, they said, here you go, room 401.”

He was in a class with 52 female students where Sammarco taught history for three years, but eventually it came time to settle down in the suburbs, and the commute to the city became too much. A friend helped him get a job at Plainview High School teaching history. He was there for 19 years. He spent his free time teaching at a Jewish community center and homeschooling sick children at a mental institution.

“The parents said he was such a wonder to their kids,” said his wife, Janet Sammarco.

One year, the journalist Geraldo Rivera ran a feature story about wanting to raise money for schools with special needs. Sammarco decided to throw a carnival at the high school and get his senior students involved. They raised $9,000 dollars.

“Some parents in Plainview say it was the best thing that ever happened to Plainview… that all the kids did something good,” said Sammarco.

But it was not just one single event that stands out to him. “The whole experience was rewarding,” he said. “Seeing kids grow. I had the same kids for a year so I could see the difference between when they started and the end. Plainview had really good students. Oh, they were bright. It was a good feeling, if you don’t get that feeling. Don’t teach.”

Sammarco still remembers receiving the news of his cancer and how the idea of having to resign pained him, as he would no longer be able to teach without a voice. The students all walked him out to his car on that last day.

“All the girls were crying,” Sammarco recalled. “That was a bad day, let me tell you… I loved teaching… that was very sad. I drive out of the parking lot and they were all waving.”

He had surgery shortly after, and the whole school waited for news. Someone made an announcement on the loud speaker, saying “Mr. Sammarco made it through the surgery, he is okay.”

They could have taken only one vocal cord and left him with a voice, because the tumor was only on one vocal cord, but it was large and if even meniscal traces were on the second one the cancer would have spread further. The operation saved his life. With speech therapy he started with a method using burping up air, one he learned to laugh about. His more recent pattern of projecting air became more natural, allowing him to verbally communicate.

“People would be scared and feel bad if they couldn’t understand what he was saying,“ said Janet Sammarco. “I think we were closer. He needed me more than ever before.”

It also brought the community together and showed him how many people cared. People came to him and prayed for him.

“Losing my voice didn’t affect the quality of my life. I can’t complain about my life. I was good to my country, I helped people grow, I’m very positive about my life,” said Sammarco.

The radiation from chemotherapy led to blood and kidney cancer years later. He believed the water he drank while in Korea that had been contaminated with gasoline also contributed. Drinking that water and smoking socially are his only regrets in life, but he says he wouldn’t have changed anything.

“Did I appreciated what I had? Not really. I do now. We take things for granted… after the third cancer I was like, O.K God, I get it,” He laughed lightheartedly with a big warm smirk.

Still a young man after the surgery, Sammarco still needed to work. Sammarco went on to be the groundskeeper at his local church, St. Anthony of Padua R.C Church in Rocky Point after resigning from teaching.

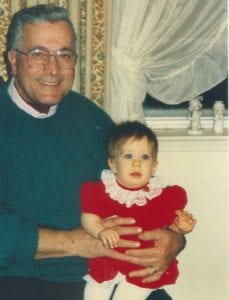

Sammarco passed away June 24. He was 88, and is survived by his wife of 60 years, Janet; his children, Peter and Jennifer; two granddaughters, Jennifer and Christine; two great-grandsons, Connor and Bryce; and his only surviving brother, Richard.

He was preceded in death by his son Robert.

“I enjoyed the 19 years working at the church and planting trees… it wasn’t that bad,” Sammarco said. “The trees will outlive me, and people will look at them and remember me driving around on the tractor.”