Evelyn Wheeler Cramer. The name now adorns a bench outside the Miller Place Academy Free Library in recognition of a woman who passed away in 2017 at the age of 93, who had long shown care for one of the few lingering historical institutions of the North Shore and Miller Place. It’s also significant, not just because of her passing, but because she had been a part of the two-story, white facade structure for close to a century.

Thomas Cramer, 66, Evelyn’s son, said that after his mother died they asked people to send e digital.donations to the library in lieu of flowers. He also inherited stock in the corporate nonprofit that runs it. Using donations, he bought the bench he said cost about $1,000 and laid bricks, which he had leftover at his own house, as a platform for the bench.

“My mother went to school there when the school district rented it for a while,” Cramer said. “I have quite a history with it, but it’s pretty much the way it’s always been.”

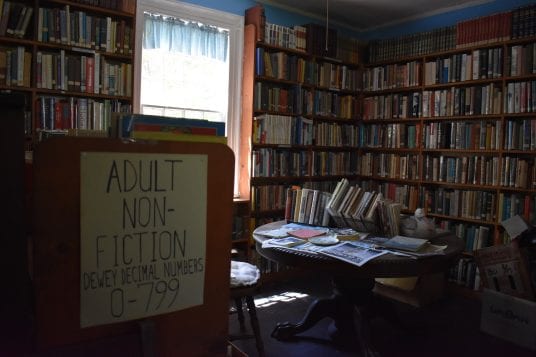

The location is considered a free library, meaning membership does not depend on people paying municipal library taxes. In fact, the location and the people who run both the library and maintain the building reveal a much stronger sense of old-time spirit. There are no computers inside, and instead volunteer librarians run everything off the Dewey Decimal System along with a card catalogue. The inside smells of old wood and dusty tomes. The place is even heated during the cold months the old-fashioned way, with a large black iron stove in the center of the space. It is the only source of heat for the entire building.

It occupies a unique space in Miller Place history. Built in 1834, the building provided secondary education that was not yet provided by New York State. Funds were raised by subscription, and students came from all over Long Island. Both boys and girls participated.

Once New York began providing secondary education, the student numbers declined and the academy was closed in 1868. While in 1894 the academy was used as a public school because the original one-room schoolhouse was in disrepair, it would later be used as a Sunday school for the Mount Sinai Congregational Church, a polling location and a forum for people to speak on various topics. Several notable people spoke there, including Martha Wentworth Suffern, the city vice chair to the suffrage party, who spoke to 80 people on women’s suffrage before they got the right to vote in 1920.

In 1934, members of the academy held their centennial celebration, where two notable old families of the North Shore were present in Corinne M. (Davis) Tooker of Port Jefferson and Elihu S. Miller of Wading River.

The Miller Place Academy is still operated by the descendants of those venerable families who bought shares to construct the building in 1834. The free library currently occupies it as a separate entity and though it’s open on weekends and hosts school trips and children reading times, there are concerns of a decline in the number of patrons.

But for Cramer, and for the many trustees who run both the nonprofit that oversees the building and the library itself, modern challenges and a declining number of patrons and the constant need for volunteers means the stewards now have to think about the future in ways they may not have before.

Richard Gass, the president of the board of trustees for the academy and a member on the free library board, has been involved for over 30 years, longer if you consider him helping his parents when they were both actively involved.

The free library was opened in 1938. Since then, it has been in continuous operation, and last year almost 4,000 books were circulated, according to the library. Volunteers do everything from preparing books to chopping wood for the iron stove. Books are replenished by subscriptions to book clubs and donation gifts from other libraries; but volunteers are all retired, and the academy board president said it has been hard to attract younger volunteers.

Gass’ mother and father Margaret and Richard Gass, had long been stewards of the place as well. They helped establish community events such as an art and craft show that lasted for nearly 20 years up until the early 1990s. Such an event occupied not just the academy’s front lawn but also neighboring lawns as well. Once Gass’ father grew too old to handle that event, it stopped, and other than biannual book sales, the lack of community participation has helped the library inch toward obscurity.

But for the families that still live in the community and love the academy building, that simply cannot happen, if not for the sake of the community’s heritage but for the community at large.

Cramer, who when he was 16 helped do an Eagle Scout project to beautify the front of the building with two large trees, now cut down, said there’s something special about the place.

“As kids, we always went up there to the library,” Cramer said. “It’s not quite Comsewogue or Port Jeff library. It’s just books, maybe not the newest books, but books. It’s unique.”

Gass said there are certainly issues with trying to modernize. While Cramer said he plans to create a website for the location, there comes a point when modernization eclipses the historical nature of a place. Should they look to install a new heating system or keep with the old? Should they find more uses for the building other than the library, or would that hurt its historical pedigree? Those are questions the academy trustees continue to ask.

“Some people love the idea of sitting in a chair, enjoying the smell of wood smoke and old books,” Gass said. “Other people complain about all those same elements. You have to really love it, but if you don’t it’s not the place for you.”