By Daniel Dunaief

At the beginning of this month, the North Atlantic started its annual hurricane season that will extend through the end of November.

Each year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration offers a forecast in May for the coming season. This year, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center anticipates a 60 percent chance of an above-normal season. The Center anticipates 13 to 19 storms, although that number doesn’t indicate how many storms will make landfall.

These predictions have become the crystal ball through which forecasters and city planners prepare for a season that involves tracking disturbances that typically begin off the West coast of Africa and pick up energy and size as they travel west across the Atlantic towards Central America. While some storms travel back out to sea, others threaten landfall by moving up the Gulf Coast or along Atlantic Seaboard of the United States.

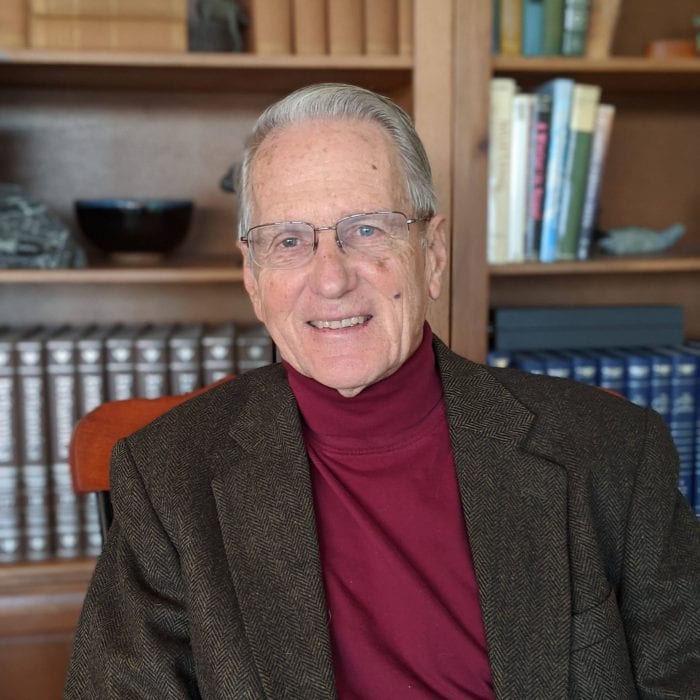

Kevin Reed, an Associate Professor at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, and Alyssa Stansfield, a graduate student in his lab, recently predicted the likely amount of rainfall from tropical cyclones.

Using climate change projection simulations, Reed and Stansfield came up with a good-news, bad-news scenario for the years 2070 through 2100. The good news in research they published in Geophysical Research Letters is they anticipate fewer hurricanes.

The bad news? The storms will likely have higher amounts of rain, with increased rain per hour.

“If you focus on storms that make landfall over the Eastern United States, they are more impactful from a rainfall standpoint,” Reed said. “The amount of rainfall per hour and the rainfall impact per year is expected to increase significantly in the future.”

In total, the amount of rainfall will be less because of the lower number of storms, although the intensity and overall precipitation will be sufficient to cause damaging rains and flooding.

Warmer oceans and the air above them will drive the increased rainfall, as these storms pass over higher sea surface temperatures where they can gain energy. Warmer, moist air gives the hurricanes more moisture to work with and therefore more potential rainfall.

“As the air gets warmer, it can hold more water in it,” Stansfield said. “There’s more potential rain in the air for the hurricanes before they make landfall.”

Stansfield said the predictions are consistent with what climatologists would expect, reflecting how the models line up with the theory behind them. She explored how climate change affects the size of storms in this paper, but she wants to do more research looking at hurricane size in the future.

“If hurricanes are larger, they will drop rainfall over a larger area,” which could increase the range of area over which policy makers might need to prepare for potential damage from flooding and high winds, Stansfield said.

While her models suggest that storms will be larger, she cautioned that the field hasn’t reached a consensus about the size of future storms. As for areas where there is greater consensus, such as the increased rainfall their models predict for storms at the end of the century, Stansfield suggested that the confidence in the community about their forecasts, which use different climate models, is becoming “more apparent as more modeling groups reach the same conclusion.”

In explaining the expectations for higher rainfall in future storms, Reed said that even storms that had the same intensity as current hurricanes would have an increase in precipitation because of the availability of more moisture at the surface.

While storms in recent years, such as Hurricanes Harvey, Florence and Dorian dumped considerable rain in their path because they moved more slowly, effectively dumping rain over a longer period of time in any one area, it’s “unclear” whether future storms would move more slowly or stall over land.

Several factors might contribute to a decrease in the number of storms. For starters, an increase in wind sheer could disrupt the formation of some storms. Vertical wind sheer is caused when wind speed and direction changes with increasing altitude. Pre-hurricane conditions may also change due to internal variability and the randomness of the atmosphere, according to Reed.

Reed said the team chose to use climate models to make predictions for the end of the century because it is common in climate science for comparison to the recent historical record. They also used a 30 year period to limit some of the uncertainty due to internal variability of weather systems.

Stansfield, who is in her third year of graduate school and anticipates spending another two years at Stony Brook University before defending her graduate thesis, said she became interested in studying hurricanes in part because of the effects of Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

When she was younger, she and her father Greg used to go to the beach when a hurricane passed hundreds of miles off the coast, where she would see the impact of the storm in larger waves. At some point, she would like to fly in a hurricane hunter plane, traveling directly into a storm to track its speed and direction.

Stansfield said one of the more common misconceptions about hurricanes is that the category somehow determines their destructive power. Indeed, Superstorm Sandy was a Category 1 hurricane when it hit New York and yet it caused $65 billion in damage, making it the 4th costliest hurricane in the United States, according to the NOAA.

After Stansfield earns her PhD, she said she wants to continue studying hurricanes. One question that she’d like to address at some point is why there are between 80 to 90 hurricanes around the world each year. This has been the case for about 50 years, since satellite records began.

“That’s consistent every year,” she said. “We don’t know why that’s the number. There’s no theory behind it.” She suggested that was a “central question” that is unanswered in her field.

Understanding what controls the number of hurricanes will inform predictions about how that number will change in response to climate change.