By Daniel Dunaief

Much as New Yorkers might want to minimize sleep, even during the pandemic when the need to be active and succeed is hampered by limited options, the body needs rest not only for concentration and focus, but also for the immune system.

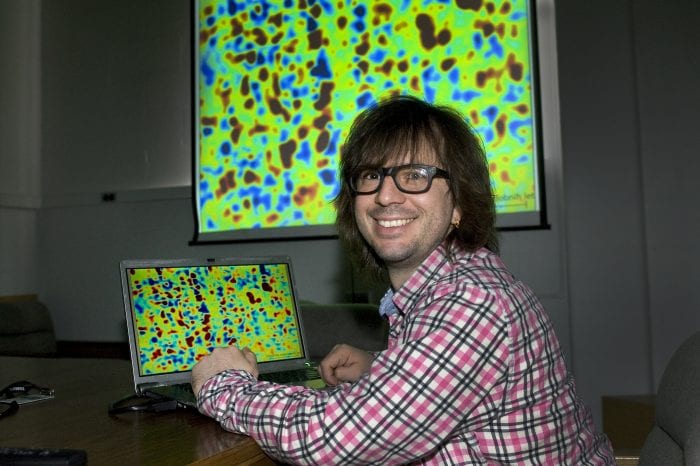

Recently, Assistant Professor Jeremy Borniger, who joined Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in January, collaborated with his former colleagues at Stanford University to publish research in the journal Science Advances that sheds light on the mechanism involved in this linkage.

Doctors and researchers had known for a long time that the release of glucocorticoids like cortisol, a stress hormone, can suppress the ability to fight off an infection. “That happens in people that are chronically stressed, even after surgery,” said Borniger in a recent interview.

A comprehensive understanding of the link between neuronal cells that are active during stress and a compromised immune system could help develop new ways to combat infections. The Stanford-led study provides evidence in a mouse model of the neuronal link between stress-induced insomnia and a weakened immune system.

Ideally, scientists would like to understand the neural pathways involved, which could help them design more targeted approaches for controlling the immune system using natural circuitry, according to Borniger.

Scientists could take similar approaches to the therapies involved with Parkinson’s, depression and obesity to increase or decrease the activity of the immune system in various disease states, instead of relying on a broader drug that hits other targets throughout the body.

In theory, by controlling these neurons, their gene products or their downstream partners, researchers could offer a way to fight off infections caused by stress.

While their studies didn’t look at how to gauge the effect of various types of sleep, such as napping or even higher or lower quality rest, their efforts suggest that sleep can help protect against stress-triggered infections.

The total amount and the structure of sleep play roles in this feedback loop. The variability among people makes any broad categorization about sleep needs difficult, as some people function well with six hours of sleep, while others need closer to eight or nine hours per day.

“Scientists are still working out how the brain keeps track of how much sleep it needs to rest and recover,” Borniger explained. “If we can figure this out, then, in principle, we could mess with the amount of sleep one needs without jeopardizing health.”

Researchers don’t know much about the circuitry controlling sleep amount. Borniger recognizes that the conclusions from this study are consistent with what doctors and parents have known for years, which is that sleep is important to overall health. The research also identifies a brain circuit that may be responsible for the way sleep buffers stress and immune responses.

People who have trouble sleeping because of elevated stress from an upcoming deadline often have a flare up of diseases they might have had under control previously, such as herpes viruses or psoriasis. These diseases opportunistically reemerge when the immune system is weakened.

The major finding in this study is not that the connection exists, but that the researchers, including principal investigator Luis de Lecea and first author Shi-Bin Li at Stanford, found the neural components.

While the studies of these linkages in the hypothalamus of mice were consistent across individuals, the same can’t be said for anecdotal and epidemiological evidence in humans, in part because the mice in the study were genetically identical.

For humans, age, sex, prior experiences, diet, family history and other factors make the linkage harder to track.

Even though researchers can’t control for as many variables with humans as they can with mice, however, several other studies have shown that stress promotes insomnia and poor immune function.

Borniger emphasized that he is the second author on the paper, behind Li and was involved in tracking the immune system component of the work.

Borniger and de Lecea are continuing to collaborate to see if drugs that target the insomnia neurons block the effect of stress on the immune system.

Now that he has moved into the refurbished Demerec Laboratory at CSHL, Borniger plans to work on projects to investigate how to use the nervous system to control anti-tumor immunity in models of breast and colorectal cancer, among others.

By understanding this process, Borniger can contribute to ways to manipulate these cells and the immune system to combat cancer and other inflammatory diseases.

Ideally, he’d like to be a part of collaborations that explore the combination of manipulating nervous and immune systems to combat cancer.

Borniger came to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory because he was eager to collaborate with fellow scientists on site, including those who look at the immune system and metabolism. He appreciates how researchers at the famed research center look at how bodies and the brain respond to a growing tumor and would like to explore how tumors “influence nerves and then, reciprocally, how nerves influence tumor progression.”

The first few steps towards working at CSHL started in 2018, when Tobias Janowitz, Assistant Professor at CSHL, saw a paper Borniger published on breast cancer and asked him to give a 15-minute talk as a part of a young scholars symposium.

Borniger grew up in Washington, DC, attended college at Indiana University, went to graduate school at Ohio State and conducted his post-doctoral work at Stanford. Coming to CSHL brings him back to the East Coast.

Borniger and his fiancée Natalie Navarez, Associate Director of Faculty Diversity at Columbia University, met when they were in the same lab at Stanford. The couple had planned to get married this year. During the pandemic, they have put those plans on hold and may get married at City Hall.

Borniger and Navarez, who live on campus at Hooper House at CSHL, look forward to exploring opportunities to run, hike and swim on Long Island.

The new CSHL researcher appreciates the new opportunities on Long Island.

“This sort of collaborative atmosphere is what I would have in my Utopian dream,” Borniger said.